The Discipline of Haircuts

by Sandip Roy

Avinash despised haircut Sundays with a burning passion. As a young boy, the arrival of Nripati-babu, the aged neighborhood barber, on the last Sunday of each month was a dreaded event. Carrying a worn-out black box containing scissors, a strop razor, and a discolored powder puff, Nripati-babu would come prepared to give Avinash his regular trim. Despite Avinash’s tantrums and protests, he was inevitably placed on a shaky stool in the courtyard, his face a picture of rebellion. Covered with a newspaper that resembled a jack-in-the-box, Avinash would reluctantly undergo the haircut ritual. Observing the unruly tufts of gray hair sprouting from Nripati-babu’s ears, he couldn’t help but feel as though his own dark hair was being uprooted like the letters on the black newsprint. Occasionally, he would catch a glimpse of his friend Indrani peering at him through their kitchen window, adding to his sense of humiliation. For a lighter read on the art of barbering, you might enjoy the Book of Barbering authored by these guys for easier and simpler understanding.

‘Why, why, why must I get my hair cut? You don’t,’ Avinash once said accusingly to his mother.

‘You are a boy and boys have short hair.’

‘Why?’

‘Because boys are one way and girls are another. And if you have long hair people will think you are a girl.’

‘So what?’

‘Well, then you don’t need to study at St John’s School for Boys. Look, I have a hundred things to do. I can’t sit here and argue with you all day. If you don’t want a haircut, don’t. We will put a ribbon in it and enroll you in St Teresa’s like Indrani next door.’

When Avinash turned seven his exasperated mother announced he was old enough to go and get his hair cut, just as his father did, at the New Modern Saloon for Gents (Air-Conditioned). She thought it would make him feel grown-up and that his passionate hatred for the ritual might dissipate. But it did not help. The New Modern Saloon was neither new nor modern but it was indeed air-conditioned. In fact, before B.C. Sen and Sons Fine Jewellers installed an air conditioner, New Modern Saloon was the only shop in the neighbourhood that boasted of one. More often than not, though, the air conditioner was turned off. ‘Electricity bill too high,’ explained Harish-babu, the head barber.

Harish-babu, as head barber, reserved his cutting talents for the more exalted customers, like Avinash’s father, a professor and thus automatically held in high regard. Avinash had to be content with Lakshman-babu who was probably ten years younger but seemed ancient anyway. They were an odd pair. Harish-babu was tall and thin with wire-rimmed spectacles and white hair that matched his spotless white shirt and dhoti. On bright summer days he glowed like a detergent advertisement. Lakshman-babu was plump and dark, with caterpillar eyebrows. On hot afternoons Avinash could see the beads of sweat gather like hungry flies on his big bald domed forehead. Avinash would stare at them fascinated, trying to will the drops to grow bigger and heavier and heavier until unable to stop themselves they would roll down his forehead. Lakshman-babu always smiled unctuously at Avinash and said, ‘Well, if it’s not the little sahib. Already time for another haircut, eh?’

Then he placed two cushions on the chair so that Avinash’s head would come up to the level of his scissors.

‘My, my, you are growing. Soon you’ll be needing only one cushion. Ha ha ha.’

Scowling fiercely, Avinash would clamber on to the footstool and then on to the chair and plant himself on the cushions. The chair was big and wide and Avinash always felt he was being swallowed whole.

‘Very good, very good,’ Lakshman-babu chortled as he wrapped a starched white sheet around him and knotted it tightly behind Avinash’s neck. He made a few practice swipes with his scissors. Then his big shiny moon-head loomed over his ear.

‘Hold still now, my little gentleman,’ he said, the fingers of his left hand brutally digging into Avinash’s neck and jamming his head in place. ‘We don’t want to cut off a bit of our ears now, do we?’

Avinash bet he did. Avinash bet he kept the ears of young boys in jars. He had once seen a whole baby with three legs in a big jar at the museum. Avinash imagined his ear floating in a jar like that.

By the end of the haircut Avinash had hair all over him and inside his shirt and it tickled and scratched. But the torture was not over yet. One final ritual was left. Lakshman-babu opened his shiny blue powder case, dabbed the pale pink worn-out powder puff vigorously in the cheap talcum powder and then daubed it liberally on Avinash’s neck raising puffy white clouds. Finally satisfied with Avinash’s parted, powdered and tamed look, he pushed the stool forward so Avinash could clamber down to freedom.

Over time the stepping stool went away and then one by one the cushions too but Avinash’s hatred for Lakshman-babu and his haircuts remained undiminished. His stalling attempts at rebellion, however, always came to nothing, thanks to Father Rozario.

Father Rozario was the school prefect. Every now and then, with no warning, he would announce hair-check days. All the boys would wait trembling as he strode into the classroom swinging his slim cane. They would have to turn around and face the wall. Avinash would smell the nicotine on his breath as he came closer and closer, his cane measuring the gap between his hairline and his collar with geometric precision.

‘So what have we here?’ Avinash could feel the cane on the nape of his neck – a gentle tap, almost a loving caress. ‘Is someone trying to be a Hindi film star?’

Little nervous titters.

‘Silence!’ The room fell quiet. ‘Turn around, turn around so I can look at your face.’

Avinash turned around slowly quaking in his shiny black school shoes.

‘What’s your name, boy?’

‘Avinash.’

‘Avinash. Avinash, what?’

‘Mitra, Father.’

‘So, Mr Avinash Mitra, can you touch your neck for me? Yes, right there where the collar is.’

Avinash touched his collar.

‘And what can you feel there?’

Avinash knew the answer because he’d heard the question so many times before. ‘Hair, father.’

‘Hair,’ Father Rozario paused as if Avinash had presented him with a curious new piece of evidence that needed to be mulled over. ‘And Mr Avinash Mitra – do your parents pay your fees so you can attend a reputable school for young men of good families or—’ here he paused for dramatic effect and then his voice took on Biblical thunderousness. ‘Or do you think you are one of those no-good loafer boys who have nothing to do all day except smoke cigarettes and style their hair like good-for-nothing Hindi movie stars?’

Without waiting for an answer, he roared on, seeming to grow larger and larger as if he would crush Avinash under his big toe. ‘We want you to become decent law-abiding citizens. Short hair is a sign of discipline and one thing that St John’s is known for is discipline. I will not let this school turn into a Bombay film studio. You are not here to become movie stars. Your parents don’t pay their good money to see you all grow into louts who can’t hold a job for two days. Do you know why they can’t?’

He jabbed the cane at Avinash and said, ‘Because they have no discipline. And discipline begins with a proper haircut.’ He glared around to see if there were any objections to his theory. Seeing none, he turned back to Avinash. ‘So, Mr Avinash Mitra, put out your hands, palms up.’

Avinash put them out, shaking.

‘Steady, hold them steady!’ Father Rozario barked. Gritting his teeth, Avinash willed his hands to stop shaking.

The cane came whistling down and struck his hand with a sting. Avinash tried to squeeze the tears back. But then the cane came down again and left another smarting stripe.

‘All right, boy, come to my office tomorrow and show me your haircut.’

Avinash nodded mutely. Beside him, Rajiv, whose turn it was next, had almost peed in his pants.

What filled Avinash with even more dread was the prospect of coming home and telling his mother everything. One week ago he was supposed to have had a haircut. But he had put up a bitter fight. He wanted to finish his book. He needed to do his homework. He had a stomach ache. He had to go to Nitin’s house. Nitin’s hair was longer than his. His was not all that long. They had just had a hair-check. Finally, exasperated, his mother had given in. ‘Fine, do whatever you want. You will find out soon enough whether your hair is too long or not.’

And now Avinash would have to tell her that he needed a haircut after all.

Then one day, soon after Avinash’s fourteenth birthday, everything changed. He had gone to New Modern for his monthly ritual and found, to his surprise, a new face. He was much younger than any of the other barbers there. As soon as Avinash saw him he had a vision of Father Rozario’s scowling face. This fellow looked just like the ‘no-good loafer boys’ they had all been warned about. His hair was long – way over his collar – and in the front it was pouffed exactly like a Hindi film star. What was even more shocking was that he had left not one, not two, but three buttons open on his dark blue shirt. In their school Arijit had been caned and given a C-grade for leaving two buttons open. Avinash could see the hair on the barber’s chest and a thin golden chain nestling in it. Harish-babu said, ‘This is Sultan. He is here because Lakshman-babu had to go to his home in Baharampur. His son was hit by a scooter.’

Avinash tried to look concerned but his eyes were hypnotized by the golden chain.

He sat down on the chair.

When Avinash saw Harish-babu coming towards him with his scissors he almost cried out, ‘No.’ He didn’t know why and he didn’t know how to say it without making a complete fool of himself but he really wanted Sultan to cut his hair. Avinash imagined that there was a small stool on the floor which Harish-babu could not see. He imagined him stumbling over it, the scissors flying out of his hand and then Harish-babu himself falling, toppling over, his white dhoti unravelling as his foot caught in it. Avinash imagined all the clumps of hair on the floor rising up like a flurry of pigeons and then settling gently on his white shirt. And his glasses, yes, his glasses would go flying off and hit the little magazine stand with old dog-eared issues of Reader’s Digest and Nabakallol. And one lens would just pop out and go spinning across the floor.

But there was no stool, and there was no escape. Avinash felt Harish-babu’s coarse fingers tying the white sheet around his neck. In the mirror he saw Sultan and was it his imagination or was he looking at him with a knowing smile? Avinash dropped his eyes in confusion. He saw men like Sultan every day – loitering with cigarettes on street corners. Some days he would stand on the balcony and see them drinking endless cups of tea and smoking. Their loud carefree laughter and scraps of heated arguments would float up, peppered with ‘bad’ words. Acutely conscious of his mother standing beside him he’d pretend he hadn’t heard. But the words would hang in the air obstinately. He would look away but would be inexorably pulled into their conversation, secretly thrilling to the swear words they tossed around with such casual bravado.

When Avinash walked home from school they would be there standing at the corner as if they owned it. The boy from the tea-stall opposite would come by with his kettle filling their cups with hot sweet milky tea. His heart always skipped a beat when he walked by them. In his clean white school uniform with his striped school tie, Avinash felt like a creature from another planet. He was a mother’s boy without his mother to protect him. Avinash felt that they looked at him with the contempt that is reserved exclusively for mothers’ boys. Every time Avinash walked by the corner he would brace himself for a taunt, an insult tossed his way as casually as a cigarette butt. He would swing his satchel on his shoulder and loosen his tie with what he hoped was casual style. Once he even unbuttoned the top two buttons on his shirt. But then Avinash saw Madhu’s mother, who worked next door, returning from the ration shop and quickly buttoned up again. Then he would walk past the young men quietly, his eyes firmly on the road, not sure whether he was hoping they would not notice him or whether he was hoping deep inside him that they would.

Sultan had probably been there as well – laughing uproariously at some dirty joke. And now here he was barely three feet away from him cutting the hair of some fat man who was almost bald anyway. Avinash wanted him to cut his hair because he didn’t know how else he could talk to him. Maybe he would ask him to have a cup of tea with him. But that was just fantasy. In real life Avinash knew he could say little to him other than ‘No, shorter.’

‘Can’t we turn on the air conditioner, Harish-babu?’ Sultan said, wiping his brow.

Harish-babu froze, scissors in mid-air. ‘Air conditioner?’ he said slowly enunciating each syllable.

‘Yes,’ said Sultan calmly. ‘This is supposed to be air-conditioned, isn’t it? Look, that’s what it says.’ He gestured towards the door. ‘New Modern Saloon for Gents (Air-Conditioned).’

Harish-babu slowly lowered his scissors. In all his years at the saloon he had never encountered such insolence. And in front of the customers too.

‘Well,’ he said quietly, ‘do you know how much it costs to run the air conditioner? Perhaps I should take it out of your salary. Perhaps then you’ll understand that money doesn’t just grow on trees.’

‘Well, then you shouldn’t say air-conditioned,’ said Sultan evenly, pausing to admire his handiwork on the fat man’s head. ‘I mean, if you don’t run the AC in the middle of summer, what’s the point?’ Harish-babu put down his scissors. Avinash was afraid he might drop them on his head. Then he turned round to face Sultan who was still snipping the fat man’s hair as if nothing had happened.

‘The point is that we have an air conditioner,’ said Harish-babu, his voice so tightly controlled it seemed to twitch. ‘And it is my decision as to when we want to run it.’

‘But don’t you think it makes sense to run it on a hot afternoon like this?’ said Sultan, cocking his head to inspect the fat man’s pate. ‘I’m sure your customers would agree, wouldn’t you?’ Now he looked straight at Avinash and raised one eyebrow questioningly. Trapped between them Avinash squirmed. He felt Harish-babu’s lightly laid hand on his shoulder tighten its grip.

Sultan’s eyes held his with easy familiarity.

Avinash flushed and swallowed.

‘Well?’ said Sultan smiling, ‘Isn’t it hot?’

‘Yes,’ Avinash replied. ‘Yes, it is.’ His words came out as a squeak. But with those words, Avinash had a feeling that he had just taken a huge hatchet and hacked away the ropes that tied his boat to the shore and he was now floating away, uncontrollably, into the ocean. Harish-babu’s fingers clenched tighter.

‘Yes,’ chimed in the fat man. ‘After all, you charge three rupees more than Prince Saloon across the street.’

Harish-babu let go of Avinash’s shoulder and stalked over to the air conditioner. He turned it on and as it grumbled into life Avinash looked up into the mirror. He caught Sultan’s eye as he bent over the fat man’s head. There was a half-smile on his lips and when he saw him looking Sultan grinned and winked.

Avinash blushed and looked away. Harish-babu returned to his chair and said icily, ‘I trust the little sahib is feeling cooler now.’ Then he turned to Sultan and said, ‘When you open your own saloon you can keep the air conditioner running eight hours a day if you like. But here I make the rules.’

‘Of course I will,’ said Sultan. ‘Why eight? I’ll run it twenty-four hours a day.’

Then he started humming a hit song from the latest Hindi film. Avinash looked at him several times excitedly, hoping he would accord him new respect as a fellow-rebel, a comrade-in-arms. But he seemed to have forgotten Avinash was there.

That night Sultan appeared in his dream. Avinash did not remember anything of it except that he woke in the morning with his image graven in his head and he knew he had been in his dream. He closed his eyes and tried to go back to the dream, to see what they had been doing together. But it was gone. But he knew whatever it was, it had been painfully pleasurable in a way that only truly secret secrets are.

The next time, Avinash went for his haircut with an eagerness that surprised his mother. She had wanted to take him to the fancy Ennis Ladies and Gents Saloon near his father’s office because she wanted her hair trimmed as well. But Avinash insisted on going to New Modern.

‘That boy just never ceases to amaze me,’ she complained to her husband. ‘For years he fusses about going to New Modern. And now when I offer to take him to Ennis he only wants to go to New Modern.’

‘It’s that age,’ said his father soothingly. ‘He just wants to be contrary. Why don’t you start offering to make him tea? Maybe then he’ll suddenly want his milk too.’

But the moment Avinash walked into the shop his heart sank. The air conditioner was turned off. Lakshman-babu was back. There was no sign of Sultan. Avinash didn’t know how to find out where he’d gone. He didn’t want to show that it mattered to him, that he even remembered that there had been another barber named Sultan. He sat down on the chair and let Lakshman-babu tie the sheet around him.

‘So,’ Avinash said redundantly, ‘you are back.’

Lakshman-babu just knotted the sheet tight behind his neck.

‘Hmmm, so what happened to the other barber?’ Unable to stop himself, Avinash plunged on recklessly. ‘Ummm, what was his name?’

‘Sultan,’ said Lakshman-babu shortly. ‘He’s gone.’

‘Oh,’ Avinash said. ‘Was he from your village?’ Avinash ventured.

‘Of course not. We don’t have smart-alecs like that in the village. Our village has honest hard-working men of the soil. He was a city boy, that Sultan. Too cocky for his own good. Will come to a bad end, mark my words.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘No respect. Just shooting off his mouth like this was his own property. Harish-babu told me everything.’ Lakshman-babu shook his head in dismay. Then he leaned forward so that his mouth was almost in Avinash’s ear. ‘Young people these days. No discipline. No discipline at all.’

‘But,’ Avinash said, undeterred, ‘where did he go?’

‘Hell, for all I care,’ said Lakshman-babu. ‘What would you want with the likes of him? You are a good, well-mannered boy. Your parents are bringing you up with so much care. You are so lucky. Not like that Sultan. If he was my son I’d have straightened him out long ago.’

Two days later, Avinash bumped into Sultan just like that. Avinash was out shopping with his mother when he saw him at the street corner with a group of other young men. A couple of them were from his neighbourhood. Sultan was smoking and talking animatedly. He was wearing a black shirt and and had the same thin gold chain around his neck. Avinash wanted to run up to him. Instead he just stood there unable to move. His mother was bargaining fiercely over the price of tomatoes. Avinash stood by her, clutching the bag of groceries, sneaking looks at Sultan. Avinash wondered if he would remember the air conditioner and how they had fought Harish-babu together.

He looked at the cigarette between Sultan’s fingers and suddenly imagined him turning around and asking him if he wanted a drag. The image was so sudden and so vivid it shook him. Sultan looked up to hail the boy from the tea-shop across the street. For a moment their eyes met. Avinash opened his mouth to say something.

‘Who are you gaping at?’ said his mother. ‘Put these tomatoes in the bag.’

‘Look,’ Avinash said. ‘That’s my barber.’

His mother glanced over and said with a frown, ‘Him? I didn’t know they had people like him at New Modern. How can he give a haircut? He doesn’t look like he ever gets one!’

Sultan looked over. Avinash smiled uncertainly. And then, plucking up all the courage he had, he said what he already knew. ‘You don’t work at New Modern any more.’ He meant it to be a question but it came out more as an accusation.

Sultan’s friends turned around to look at him. His mother, who had been examining some green chillies, suddenly looked up with a frown. Avinash felt the whole street teeter and he felt hot with embarrassment.

Then Sultan laughed. ‘Oh no – not with that old miser. Now I have my own place with my cousin Aziz. It’s called Badshah, right on Lake Avenue across the street from the temple. It doesn’t have air conditioning yet, though.’

‘Let’s go,’ said his mother, abandoning the chillies.

As they went off Avinash looked back to see if Sultan was looking at him. He was not, but at least he had remembered.

It doesn’t have air conditioning yet, though. He remembered.

‘Well, good for Harish-babu,’ said his mother, marching down the street. ‘Once you let people like that in, business goes downhill. You go in for a haircut, you’ll come out looking like a two-paisa film star.’

Barely a week later, Avinash decided that his hair was too long and he needed a haircut.

He walked by the Badshah saloon three times to make sure that Aziz had a customer and Sultan was free. Then glancing around to see that no one was looking he walked in as nonchalantly as he could. Sultan was reading the newspaper and looked up as Avinash came in. If he was surprised to see him he didn’t show it. He just put the paper down and said, ‘Haircut?’

Avinash nodded, not quite trusting himself to speak.

Sultan was wearing a dark blue shirt and brown pants of some slightly shiny material. Avinash could see the blue straps of his sandals. The shirt was not tucked in and the first two buttons were, as usual, undone. Inside he wore a white vest. Avinash could see a few strands of chest hair peeping over the top of his vest and for some inexplicable reason that made his heart pound. Avinash had seen the hair on his father’s chest many times but it had never made his heart go faster. He wondered if Sultan would notice that he too had left one button undone on his own shirt or that his pants were a little too tight. But Sultan did not say anything.

‘Sit down,’ he said pointing to a chair.

Avinash sat down and then said, ‘Oh, I must not spoil the shirt with hair. Can I take it off?’

‘Yes, but you’ll get hair all over yourself then.’

‘I know, but my mother will kill me if I get hair all over the shirt.’

Sultan shrugged and handed him a hanger.

Avinash started unbuttoning his shirt, sure that his ears were bright red. As he sat down on the chair again he saw in the mirror his scrawny body, the flat chest with all the ribs showing through his white banian and wished he’d kept his shirt on. But it was too late. Sultan was preparing to drape the big white sheet around him. Avinash felt Sultan’s fingers knot it behind his neck and then his hands patting the sheet down over his body. His heart was racing like an express train.

Sultan opened his drawer and took out his scissors and clippers.

‘So how do you want it – short?’

Avinash wanted to say, ‘Like yours.’ Sultan’s hair was brushed up in front and carefully styled at the back so it just curled over his collars. His sideburns were long and angled. But Avinash knew that was never going to work as long as there were hair-checks.

‘Yes, short,’ Avinash said, resigned.

Sultan started humming a song as he began to snip the hair on the back of his head. Avinash sat there watching him through the mirror as if memorizing him, – the packet of cigarettes that showed through his shirt pocket, the watch with its stainless steel band, the golden chain always around his neck. Avinash tilted his head slightly to get a better view of him.

‘Hold still now,’ Sultan said holding him in place. The touch of his hand was warm and rough, almost electric against his skin and Avinash suddenly had a vision of holding his hand to his nose. What would it smell of – tobacco and hair-cream? He was acutely aware of his bare body under the sheet. Though there was no air conditioner, Avinash could feel goosebumps on his arms.

‘Sultan, I am going to get some tea,’ Aziz said.

‘Okay, can you get me a cup too?’ Then he looked at Avinash and said, ‘Do you want some?’

‘I don’t drink tea,’ Avinash said without thinking and then instantly regretted it.

‘Oh, are you still drinking milk?’ said Aziz laughing. ‘You are getting a moustache now – when will you start drinking tea?’

‘Let him be,’ Sultan said. ‘Look how skinny he is. He needs milk.’

Now Avinash wished he had never taken off that shirt. He watched Aziz leave the shop, the swivel door swinging behind him. Sultan was standing beside him now his body turned towards him as he cut his hair. His chest was at the level of his eyes. Avinash could see every strand of black silky hair pushing past the confines of Sultan’s vest. Avinash wondered what it would be like to touch them. Would he get hair on his chest too? His fingers itched to play with Sultan’s chest hair. Avinash edged his hands forward so that his fingers were almost touching Sultan’s leg.

Sultan moved forward and Avinash’s clenched knuckles grazed his pants. Sultan made no attempt to move his leg away. His heart beating with some delectable fear, Avinash left his hand there. As Sultan leaned in to trim his hair his legs pressed against Avinash’s knuckles. Avinash found himself wondering if his legs were hairy too. He felt he was sweating. And then he felt cold. Sultan raised his arm to hold his head firmly and Avinash could see the dark half moon of the shadow of his sweat in his armpit.

‘Oh, you are very fidgety,’ Sultan said.

Avinash looked up and he was smiling. His teeth had tobacco stains. Avinash smiled back. He was so very close to him. His hand pressed even more firmly against his trousers. Sultan smiled and his hands rested lightly on his shoulders. Very gently he started pressing Avinash’s shoulders, kneading the muscles through the cloth.

Then Avinash felt him go behind him and his hands unknotted the white sheet. It drifted down his body and settled on his lap.

‘Look at all the hair on your chest,’ Sultan laughed. ‘It’s almost as hairy as mine.’

He was rubbing him with a towel now brushing away the hair.

‘Oh, it’s not as hairy as yours,’ Avinash protested. ‘How old were you when you got hair on your chest?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Maybe seventeen or eighteen. But I don’t have that much – you should see my father.’

‘Really? It looks like a lot to me.’

‘No – see,’ Sultan said tugging his vest down with his finger.

‘I can’t see,’ Avinash complained.

He unbuttoned the other buttons and pulled down his vest further, exposing his chest. He was right – his hair grew like a dark soft feathery fan in the middle of his chest. More than anything else Avinash wanted to touch that hair. He wanted to trace it like a river on an India map and follow it down his belly and then he wanted his finger to burrow under his pants and trace it all the way down. All the way. Avinash shut his eyes terrified about where this was leading.

‘Touch it,’ said Sultan, his voice as silky as his hair, his tone teasing, almost a dare. Avinash kept his eyes shut but his fingers reached out of their own accord. As they traced the silky roughness of Sultan’s hair he felt the room grow stiflingly small, his own clothes uncomfortably tight. Sultan was no longer humming anything. Instead he moved closer to Avinash, his trousers rubbing up against his legs, at first casual and then insistently. Avinash realized his fingers were a hair’s breadth away from the buckle on Sultan’s belt. Avinash touched Sultan’s crotch and jerked back as if he had touched something scalding because he knew that if he pulled that zipper down there was no going back.

Just then Sultan laughed and said, ‘There, you are all done.’ He opened his eyes and saw the sheet still around him. Sultan was holding a little mirror behind him so Avinash could look at the back of his head.

‘Is that all right?’ he asked.

Avinash nodded for his mouth was too dry and his tongue too thick and twisted to trust with words. Sultan took a small towel and vigorously rubbed him. The roughness of the old towel seemed to set off sparks on his skin. Then, too soon, he stopped and handed him his shirt. Avinash’s fingers were all thumbs as he buttoned it.

As Avinash paid him, Sultan said ‘Wait, you’ve buttoned the shirt all wrong.’ Avinash just nodded and bolted from the store. ‘Come back again,’ Sultan called after him.

Avinash turned around. Sultan was standing at the door lighting a cigarette and looking at him. As their eyes met he smiled, and Avinash was not sure if he had imagined everything.

That night Avinash dreamt of him but he was in the old shop and then his mother was scolding him and Avinash woke up trembling with fear and guilt. But when he closed his eyes he saw him again standing at the door looking at him and smiling. And Avinash wondered what would happen if he just walked back, past the newspaper store, past the tea-stall, past the sleeping dog, up the two steps and Sultan shut the door behind him.

A few days later as Avinash was walking down the street he saw Sultan sitting on the steps in front of his shop. He was smoking a cigarette and chatting with the man who sold newspapers and magazines in the little stall down the road. Sultan saw him and grinned and waved, wispy tendrils of smoke curling up from his fingers. Caught in his grin, like an animal in the headlights of a car, Avinash suddenly knew he could not walk past him without remembering his dream and the strange feeling in the pit of his stomach. He stopped short and pretended he had just remembered something on the other side of the road. He turned and ran across the road almost knocking over a boy on a bicycle going the wrong way. The boy teetered down the street, a few choice curses wafting in his wake like Sultan’s cigarette smoke.

Once safely on the other side, Avinash looked across the street to see if Sultan had noticed his flight, if he was looking to see where Avinash had run off to. But he had gone back to his conversation. Avinash saw him toss his head back and laugh, his teeth white against his tan. He ran his fingers through his hair and Avinash shivered uncontrollably. He stood there for a couple of minutes trying to will him to turn and seek him out. But he carried on unconcerned, as if he had forgotten how their paths had almost intersected, before Avinash ran away. Then he finished his cigarette and stubbed it out with his sandal, stood up, stretched and wandered back inside his shop.

Avinash never went back to get his hair cut at Sultan’s again. One day he noticed the Badshah saloon had gone out of business. When Avinash got married and had a son, Amit got into St John’s School as well. ‘Like father, like son,’ Avinash’s mother said with a proud smile. Father Rozario was still there, as were hair-check days, but these were different times and no one got caned for long hair any more. Instead, they were fined.

Unlike Badshah, the New Modern Saloon for Gents (Air-Conditioned) survived. But Avinash refused to take Amit there for his haircuts. Harish-babu had died and Lakshman-babu was now in charge. Avinash took Amit to a far more expensive saloon even though it was much further away, something the boy’s grandmother thought of as a ridiculous indulgence bound to spoil the child. Sometimes on lazy holiday afternoons she would tell her grandson the story of how his father hated having his hair cut. The story was part of family lore now, worn into familiarity by its telling, rendered perfectly harmless, even slightly boring.

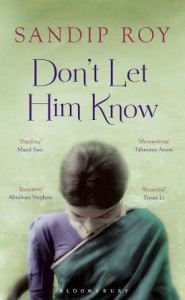

(Extracted from Don’t Let Him Know ©2015 Sandip Roy. Published by Bloomsbury.)

![]()

Sandip Roy is the author of Don’t Let Him Know. He is a senior editor at Firstpost.com, one of India’s leading digital news outlets. He is also a commentator for Morning Edition on NPR and his weekly audio dispatch from India airs on public radio station KALW 91.7 FM in San Francisco. His work has appeared in several anthologies including Storywallah!, Contours of the Heart, Men on Men 6, Mobile Cultures. He has won awards for journalism from the South Asian Journalists Association, NLGJA and others. He currently lives in Kolkata. Don’t Let Him Know is his first novel.

Sandip Roy is the author of Don’t Let Him Know. He is a senior editor at Firstpost.com, one of India’s leading digital news outlets. He is also a commentator for Morning Edition on NPR and his weekly audio dispatch from India airs on public radio station KALW 91.7 FM in San Francisco. His work has appeared in several anthologies including Storywallah!, Contours of the Heart, Men on Men 6, Mobile Cultures. He has won awards for journalism from the South Asian Journalists Association, NLGJA and others. He currently lives in Kolkata. Don’t Let Him Know is his first novel.

Heartbreaking.