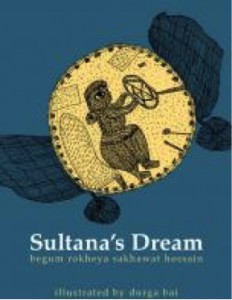

Sultana’s Dream By Begum Rokheya Sakhawat Hossain

Reviewed by Dipika Mukherjee

Sultana’s Dream, first published by Tara Books in 2005, has been reissued in 2014. It features gorgeous black-and-white illustrations by the award-winning Gond artist Durga Bai, who illustrated the children’s book The Night Life of Trees, which was also published by Tara Publishing. This independent press based in Chennai, South India has a reputation for publishing adventure stories from around the world.

Sultana’s Dream was first published in 1905, ten years before the American feminist and novelist, Charlotte P. Gilman, presented her feminist utopia, Herland. Yet Sultana’s Dream languishes in relative obscurity, and even those interested in feminist science fiction are often ignorant of this work that describes reversed purdah (the seclusion of women) in Ladyland. In Hossain’s work, peace-loving women overpower war-hungry men through scientific thinking, in a fable that redraws the line between traditional gender roles and scientific innovation. What makes this story extraordinarily compelling is that Begum Rokheya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932) was a leading feminist writer in undivided Bengal during the early 20th century. She wrote as a woman in purdah at a time when Indians under colonial rule had limited personal freedom. She is well known for her social work (she established the first school for Muslim girls, which still exists). The following passage offers a taste of Sultana’s Dream and its boldness for its times:

‘But dear Sultana, how unfair it is to shut in the harmless women and let loose the men.’

‘Why? It is not safe for us to come out of the zenana, as we are naturally weak.’

‘Yes, it is not safe so long as there are men about the streets, nor is it so when a wild animal enters a marketplace.’

…

‘As a matter of fact, in your country this very thing is done! Men, who do or at least are capable of doing no end of mischief, are let loose and the innocent women, shut up in the zenana! How can you trust those untrained men out of doors?’

‘We have no hand or voice in the management of our social affairs. In India man is lord and master, he has taken to himself all powers and privileges and shut up the women in the zenana.’

‘Why do you allow yourselves to be shut up?’

‘Because it cannot be helped as they are stronger than women.’

‘A lion is stronger than a man, but it does not enable him to dominate the human race. You have neglected the duty you owe to yourselves and you have lost your natural rights by shutting your eyes to your own interests. ’

Modern feminist writers such as Taslima Nasrin cite her as an influence, and with good reason. She is a worthy successor to Khana, the Bengali poet and astrologer, who composed poetry some time between the ninth and 12th centuries AD, and whose tongue was severed to silence her talent. Hossain was quite prolific, and one can only hope that academics and activists, especially in the western hemisphere, will soon rediscover her remarkable oeuvre.

This book is a slim volume, with unnumbered pages. It is dated, no doubt, and surely the description of helicopters and rain harvesting and solar power would have been more astonishing at the beginning of the 20th century. Some of the writing is quite naïve; Bengalis used to the flawed governments headed by women – Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal and Khaleda Zia & Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh – will surely read the following lines as ironic:

“’Since the Murdana system has been established, there has been no more crime or sin; therefore we do not require a policeman to find out a culprit, nor do we want a magistrate to try a criminal case.’’

Sultana’s Dream resists categorization. It could be read as a fable for young adults or even younger children; certainly the brevity of the story is conducive for younger readers. Yet it is also a nuanced feminist treatise, questioning religious and social practices, as well as the performance of hetero-normativity implicit in the conventions of that time and even now. One hundred and nine years after this story was first published, it endures as a fascinating commentary on the freedom of women’s bodies in urban spaces and the power of the feminine imagination.

![]()

Dipika Mukherjee is a writer and sociolinguist. Her debut novel, Thunder Demons (Gyaana, 2011), was long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize. She also won the Platform Flash Fiction competition in April 2009. She has edited two anthologies of Southeast Asian short stories: Silverfish New Writing 6 (2006) and The Merlion and Hibiscus (2002), and her first poetry chapbook, The Palimpsest of Exile, was published by Rubicon Press in 2009. Her short stories and poems have appeared in publications around the world and have been widely anthologized. She is a Contributing Editor to Jaggery (A South Asian Diasporic Arts and Literature Journal) and curates an Asian/American Reading Series for the Literary Guild, Chicago. She lives in Chicago and teaches at Northwestern University. More information at dipikamukherjee.com

Great!

I first heard of “Sultana’s Dream” via the fanfic “Fifty Years in the Virtuous City”, which I highly recommend as a more character-driven look at this particular utopia.