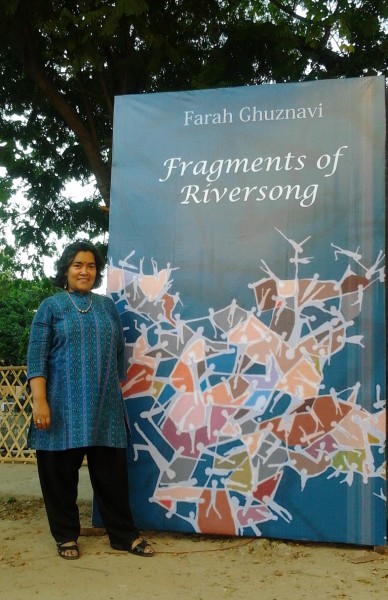

Fragments of Riversong by Farah Ghuznavi

Reviewed by Susmita Bhattacharya

“Short stories are tiny windows into other worlds and other minds and other dreams. They are journeys you can make to the far side of the universe and still be back in time for dinner.”

?Neil Gaiman

Indeed, Farah Ghuznavi’s collection of short stories is an opportunity to journey to Bangladesh, to live alongside the characters and share their dreams, aspirations and fears.

Ghuznavi’s job as a development worker in areas such as political participation, microcredit loans for the poor, adult education for women and human rights for organisations that included British NGO Christian Aid, Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, and the United Nations, has inspired her to write about the themes dealt with in her stories. In her own words: “I began writing fiction because I felt it important to tell many of the stories of people I’ve encountered in my life as a development worker, who sometimes aren’t in a position to tell their own stories” (The Missing Slate). The stories in this collection range from issues about domestic and child abuse, rape, bereavement, poverty, disasters and childhood experiences. Ghuznavi tackles these issues truthfully, without stalemate situations, with a fresh point of view. There is an overall sense of empowerment and optimism.

“Big Mother,” inspired by the Rana Plaza garment factory collapse in 2013, follows the life of Lali, a poor village girl who loses her husband in the disaster and is waiting for her US visa. She reflects on her life and why the decision to move to another country is a matter of urgent concern. “Escaping The Mirror” is a story about Dia, who is at the other end of the economic spectrum. A self-assured little girl, Dia finds herself a target of sexual molestation by the family chauffeur. After years of trying to dodge his moves, succumbing, and keeping secrets, Dia reveals her trauma to her father. Both these stories deal with child abuse and rape, and the shame and trauma a young girl experiences and for which she assumes herself to blame. Ghuznavi’s description of the predator is chilling, driving home the point that normal, day-to-day experiences can turn into nightmares when involving the wrong people. Here is an illustrative portion from her writing:“Minhas had started to use the rear-view mirror to watch her as she sat in the back. Dia would move from one end of the backseat to the other, but to no avail. Wherever she sat, he would simply adjust the mirror to ensure that she couldn’t escape his eyes” (101).

Balancing these stories of oppression are light, humorous ones, which bring out the childish playfulness and the innocent relationships children share with their loved ones. “The Guava Tree Rebellion” is one such story, in which we share the world of Nawara and her grandmother, Nanu. It is easy to feel the love between the two, despite Nanu’s great efforts to be strict and behave appropriately in front of her young charges.

The epistolary story, “Old Delhi, New Tricks,” is told from the point of view of a traveller visiting Delhi with a friend, both eating their way through the city. The description of the foods like the various grilled meats, kebabs and the ‘mandatory paan’ to provide a ‘narcotic kick to the senses’ and reactions from the locals towards tourists is very apt and humorous. It is a welcome change from the heaviness of the previous stories.

Juxtaposing images of abundance and rich food is “Waiting,” set in Dhaka during Ramzan, the month of fasting. Told from the point of view of children, which Ghuznavi does with sensitivity and accuracy, it is about extremes of great hunger versus gluttony. It is also about understanding the plight of others more unfortunate than ourselves, and how one tiny good turn could mean a cherished memory for another. The two beggar children, Hashem and Raya, starving beyond their ability to cope, are suddenly gifted with ice cream by a stranger on a hot, sultry day. One can feel their stunned amazement at tasting something so elusive for them. And one can also feel the heartbreak when Hashem “folded the ice-cream wrappers, carefully placing them for later; there were always remnants to be found on the paper. That was how he and Raya knew what Choc-bars tasted like.”

Ghuznavi’s stories tackle day-to-day issues with sincerity and realism without being judgmental or moralistic. While her stories are about the empowerment of women, they do not degrade men. Each character lives in a realistic world that we recognize. Our own stories and lives bounce back to us from the pages of this book.

![]()

Susmita Bhattacharya achieved a distinction for her M.A. in Creative Writing from Cardiff University and is widely published in the UK and internationally. Her short stories have appeared in Wasafiri, Litro, ElevenEleven, Riptide, Penguin-India, Planet, BBC etc. Her debut novel The Normal State of Mind will be published by Parthian Books in January 2015. She facilitates writing workshops in the community. She blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk. Follow her at Twitter: @Susmitatweets. She lives in Plymouth, UK.

A concise, incisive and illuminating review of a marvellous collection of short stories. A very well written indepth review that spurs the reader to get a copy of Farah Ghuznavi’s “Fragments of Riversong” and read it as soon as one can; not to speak of roving the internet to find some of the reviewer’s own short stories.

Augustine of Hippo wrote “The world is a book and those who don’t travel read only a page”. South Asia is a melting pot and to think of it as anything else does it grave injustice. So for the South Asians who chose to get educated in the Commonwealth, it’s good to remember who is the master and who is the slave if people are into playing that game of the victimization of being oppressed. There are the outward appearances and than the workings of the mind. Maybe it all comes down to what arises from the ashes of the phoenix–is there better vision, is there a better calling for the sufferings of humanity or does one just become a pawn for the playing of others? I am certain that is a question pondered by many Nobel laureates from the region.