Interview: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni on Books for Young Readers

by Uma Krishnaswami

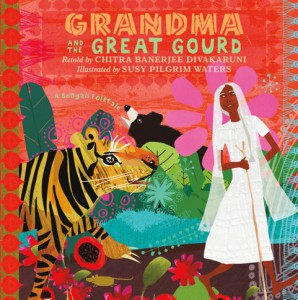

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni is a novelist, poet, short story writer, and respected teacher of writing. Chitra has most recently written a picture book, Grandma and the Great Gourd, a retold traditional tale illustrated by Susy Pilgrim Waters and published by Neal Porter Books/Macmillan. She’s also written a fantasy trilogy for children, The Brotherhood of the Conch, with an appealing child protagonist venturing upon an improbable quest. What’s different about the series is not the adventure story itself, interesting though that is, nor its Indian setting. Rather, The Conch Bearer and its sequels are unusual in that they draw from the cultural and literary history of their setting in a consistent, organic way. The conch itself, the visitor who creates a feast out of minimal offerings of food, the rejection of a heaven-like place in favor of loyalty and friendship—each of these themes echoes aspects of Hindu mythology, so culture and myth in The Brotherhood of the Conch feel structural and not merely decorative.

I wanted to talk to Chitra about her books for young readers, so we traded e-mails over a couple of months. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

[Uma] What are the elements you look for in a great children’s book? How is this different from what you’d seek in a novel written for adults?

[CBD] I look for a great story, first of all. A plot that is interesting, characters that I can relate to and like and that inspire me in some heroic manner, a positive message. In a novel for grown-ups, I like more complexity. I don’t need the characters to be likable as long as they interest me. A darker world, if it’s appropriate. And I prefer to figure out my own message, which may also be a dark one. And plot can be secondary to character and theme.

[Uma] Messages, though, leave us at risk of tilting toward didacticism. What’s the line between inspiring and positive and overly didactic?

[CBD] A message that works for children has to rise out of a character’s understanding of the situation—particularly the understanding of a young protagonist whom the reader likes. It should be something that the protagonist has been struggling with for a while, maybe a decision he or she needs to make, or a problem he or she has to overcome. That way, the message is dramatic and not didactic. Otherwise it will not touch the reader. Messages can be general—a sense that compassion is important, for instance, or that people are complicated; they come in shades of gray rather than white/black, and therefore, we cannot jump to conclusions about them.

[Uma] Your Conch Bearer books were way ahead of their time, blending adventure and mythology in an Indian context. You’ve said you wrote those for your children. What would you want child (and grown-up) readers today to take away from those books?

[CBD] The things I mention above were important to me in writing The Conch Bearer. I wanted a story that would be a great adventure for readers, but also one that would introduce readers to the Indian landscape, Indian ways of life, and Indian philosophy and values. I wanted a magical object out of Indian myth. I wanted a reverse quest tale (returning a magical object to its original home). I wanted readers to be able to relate to the two main characters, and it was important for me to make one of them male and one female.

[Uma] Thank you. Those intentions carry a different weight when you’re writing for readers who are learning to engage with text as they encounter yours. But what about even younger readers and listeners, the audience for picture books? You’ve written a story retelling in picture book form, Grandma and the Great Gourd, which Booklist described as “[c]olorful in more than one sense of the word.” Talk about this book for a bit. What made you turn to this retold folktale from your own childhood, and what memories and sensibilities did you draw upon to write it for a picture book audience?

[CBD] This was a story that my grandfather used to tell me in Bengali when I was little, so I have a personal connection to it. I also love this story (as a woman) because the hero is a clever grandmother, and in today’s world when age is seen as a disadvantage, this is a good role model for children to see.

[Uma] Yes, she’s wonderful, this grandmother. She’s clever, even crafty, and she doesn’t achieve her ends on her own. Rather, the answer to her problem lies in resourcefulness and family. But I want you to talk about the text of this book—the rhythms and word choices are strong and evocative, and they conjure up the setting as sharply as the mythic references in the middle-grade novels do.

[CBD] In rewriting this story in English, I focused on Bengali onomatopoeic sounds (for example khash khash for lizards moving on dry grass). I also liked the repetitive structure with the grandmother meeting one animal after another as she journeys through the dark forest. I think this structure is artistically pleasing and one that children take great pleasure in.

[Uma] It’s a deft marriage of the picture book form that is by definition read out loud and so needs a certain auditory quality, and the oral origins of this story that clearly carried that quality in their original Bengali. Do you have any other projects for young audiences in the pipeline? Can you share something about them?

[CBD] I have a number of other folktales in mind, oral Bengali stories that are not available in English. I would love to have the chance to share them with children here in America.

[Uma] And one last question: this was your first picture book. What did the form teach you?

[CBD] It taught me how to meld text and image to create a whole. For instance, early in the story the grandma receives a letter that will cause her to start off on her journey through the forest. I had the idea that a bird should bring the letter. But I did not put that in the text. I told the illustrator, and she drew it in.

[Uma] On the page, gestures like this, created by the writer and picked up in illustration, can go a long way to making the story feel seamless. Thank you, Chitra! I wish you much joy in your writing and teaching journeys, and I hope your path leads to more offerings for young readers.

![]()

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of many books for children. She currently serves as faculty chair in the low-residency MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of many books for children. She currently serves as faculty chair in the low-residency MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

the interview has been very helpful to me as I am researching Children’s literature written by Indian English writers.