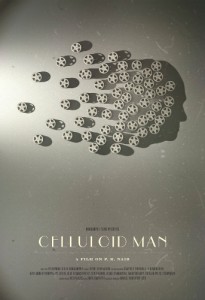

Celluloid Man: Back to the Future

By Asha Richards

India has a rich past but a poor history, laments one film savant in Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s documentary Celluloid Man. Indeed, until recently, historiography within popular culture has never knowingly been an Indian preoccupation. The most extravagant example of this cheerful indifference on display is the Indian film industry. Few films have been preserved for posterity. It is this genial disregard for the country’s rich heritage and one man’s mission to rectify that wanton lack of consciousness that shape the central theme in Dungarpur’s documentary.

Ever since Marius Sestier, the emissary from Lumière brothers, screened his clutch of short films at Watson’s Hotel in Bombay on December 28, 1895, Indians have taken to cinema with exuberance and enthusiasm. Just a few decades thereafter, the country became the world’s largest producer of films; it is reckoned that, until the advent of the first Indian talkie in 1931, 1,700 silent films were made in India. Yet fewer than twenty survive, of which just nine are complete. Most reels were destroyed, many having been stripped for their silver content, while others perhaps lie abandoned and forgotten in rusting cans in attics and dilapidated sheds.

Celluloid Man traces the heroic efforts of film archivist P. K. Nair, who indefatigably strove to search and locate, preserve, and protect as many cinematic records as he could lay his hands on. During his long tenure at the National Film Archive of India (NFAI)—established in 1964 and located in the same precincts of Pune as the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), where the once glorious Prabhat Talkies stood—Nair “begged, borrowed, and stole film prints to painstakingly build our Archive.” In his dogged tenacity, Nair brings to mind the legendary Henri Langlois (1914–77), celebrated French film archivist and cinephile, who pioneered the concept of film preservation. Langlois famously founded the world famous Cinémathèque Française in Paris, and his relentless—and sometimes controversial—efforts saw the initial collection of just ten films grow to around 60,000 within three decades.

Celluloid Man highlights the legacy of P. K. Nair and the debt the country owes this visionary. In his efforts to create and build a film archive in India, Nair traveled far and wide across India. No scrap of film was too small or too insignificant in his efforts to create a collection that would showcase India’s great cinematic heritage and provide research material for future scholars. For example, when meeting Mandakini, daughter of Dadasaheb Phalke, who is considered the father of Indian cinema, Nair acquired the first reel of Raja Harishchandra, the first-ever Indian film. A meeting with Neelkanth, Phalke’s son, later led to the acquisition of the last reel of that film. Unfortunately, the four intervening reels are still untraceable. However, thanks to a notebook in which Phalke had meticulously noted down the order of shots, Nair was able to restore the film in its entirety from scraps.

Nair was not just a tenacious collector and preserver of film, however. His encyclopedic knowledge of Indian cinema inspired students to learn more about their craft at the FTII. The documentary features interviews with star actors and directors, such as Jaya Bachchan, Naseeruddin Shah, Kamalahasan, Saeed Mirza, Ketan Mehta, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Girish Kasarvalli, and many other stalwarts of contemporary cinema, who bear testimony to Nair’s inspiration and wise counsel. In additions to these interviews, Dungarpur’s documentary contains some invaluable footage of long-forgotten historical gems of films made in different parts of the country.

After the retirement of Nair, the film archives in Pune returned to their original state of neglect and indifference—the very conditions from which Nair struggled so heroically to redeem them. For a time, Nair had continued to check on the maintenance of the archives, pointing out to the new archives head what he was doing wrong. But the new archives head, a government functionary with little or no interest in cinema, took objection and barred him from the premises. Left under the dead hand of Indian bureaucracy, it was in this shocking condition that Dungarpur found the place, creating severe problems in the making of the documentary.

Filmmaker Shivendra Singh Dungarpur began his life in cinema as assistant director to the celebrated writer, director, and lyricist Gulzar. In order to formalize his training, Dungarpur enrolled at the Film Institute and on graduation, set up Dungarpur Films, where he mainly directed advertising and corporate films. He also began to get involved with Il Cinema Ritrovato, a festival in Bologna, Italy uniquely devoted to screening restored films.

It was Martin Scorsese who changed Dungarpur’s life and cinematic ambition. Apparently, the late pandit Ravi Shankar had once mentioned to Scorsese that his brother, dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar, had made a film called Kalpana in 1948. An intrigued Scorsese, who founded the World Cinema Foundation (WCF), decided that this rare film ought to be restored to its former glory under the aegis of the WCF. Unable to get the film out of India, he sought help from within the country. It is at this point that Dungarpur found himself drawn into the process. He helped the WCF navigate the Kafkaesque maze of Indian bureaucracy and eventually facilitated the film’s restoration. Since then, this vital but unsung aspect of cinema became his passion. The freshly restored Kalpana was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012 in the presence of Uday Shankar’s widow Amala and daughter Mamata.

Film restoration renewed Dungarpur’s contact with the NFAI and P. K. Nair. When he discovered the sorry state to which Nair’s contribution and legacy had been reduced, he felt compelled to make a documentary. The result was Celluloid Man. Determined to ensure that the extraordinary contribution made by Nair would not be forgotten, and determined to carry forth his legacy, Dungarpur has thrown himself into archiving and restoring films and set up the Mumbai-based Film Heritage Foundation.

Celluloid Man has been screened across the world at over twenty international film festivals such as Rotterdam, Gothenburg, Telluride, New York, Hong Kong, and the Mumbai Film Festival. In 2013, it won the National Film Award for Best Documentary, and Irene Dhar Malik was awarded the National Film Award for Best Editor. This treasure of a film opened across India on May 3, 2013—the same day that Raja Harishchandra opened to an ecstatic audience a century ago.

![]()

Asha Richards trained at the National School of Drama in New Delhi and holds a doctorate in theater studies from the Sorbonne in Paris. She was film critic for the Indian Express newspaper in Mumbai, and later worked at the British Board of Film Classification in London. As a part-time lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London), she pioneered their course on Indian cinema. Her book Pop Culture India! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle was published by ABC-CLIO in 2006.