Cardinal Directions

by Chundra Aroor

Each day still brings newcomers: men who glare at packs of cigarettes with crimson eyes, simply pointing and pulling crumpled bills from Dickey work pants to place on the lip of the counter — as though the currency is capable of inching toward the register. Their heads are sometimes shaved, or their hair cropped close; the faces of some, however, show no traces of an encounter with a razor. He recalls, now and then, that he himself sported the same light mustache and uneven whiskers at age twelve, or thereabouts. He even thought, at first — for he feels that they glower at him — that they might be envious of the stubble on his face; this grows in densely, a dark slate color, on days when he neglects to shave.

But over the weeks and months, Atif Janjua has grown to understand that this expression is a default of sorts — these newcomers seem predisposed to looking unhappy. Perhaps back home, they grin more. Several times he has stumbled upon a couple of men, their khakis splattered with paint, whooping raucously at some joke in their native tongue. But most of the time, he sees the worried scowl of someone at an unfamiliar crossroads, measuring out the next leg of an uncertain journey. He might as well be looking in the mirror of the airport restroom twenty years ago. Back then, he too must have frowned quite a bit. Today still, there are relatively few events that give him unequivocal reason to smile.

Aside from the laborers who slump into the shop to jab a finger at a half-pint of Hornitos or hobble achily to the counter with a six-pack of Modelo Especial, he’s become aware of a new group which appeared at some point, perhaps born from the old one. It’s easy enough to see the commonalities between the two: the stature, the soft hair that parts at the philtrum. But absent from their clothes is the smeared primer, the caked plaster. Their gait too is different — precisely indirect, carving through invisible knots on the ground. Two steps forward, one back: they swagger in patterns like an embroidery needle, or as bees telling of nearby flowers. They lollop around the perimeter of the store, past bags of chips, stale rolls, and coolers, as though surveying the property; checking for loose tiles in the floor; always forming a group, usually a trio; oscillating between seriousness and humor, though these metamorphoses are not quite extreme as the sock and buskin he has seen inked on the odd forearm — Laugh now, cry later, suggests the ribbon of text below the floating masks. Half the time, they speak among themselves tersely, conspiratorially. The rest of the time, they loudly crack jokes. Sometimes, these are about him — this he knows.

They bait each other — “Trying to do a lick? You’d never pinch that, not with the Hindu there.”

“Mother fucker,” Atif Janjua swears under his breath. These kids ought to know that he is no damned Hindu. Can they not tell him from Mehta, owner of the liquor store down the block, a sour-looking man who disapproves of what he sells — shivering behind a register and flicking bead after wooden bead toward the red shock of his rosary — but would slaughter and butcher a cow himself, if he felt, by cutting out the middle man at the abattoir, he could undercut a competitor?

Atif Janjua smiles, however, when he recognizes a second mistaken identity bestowed upon him at other times by these youngsters, which was partially correct, at least in his mind — “Pinche Árabe.” Closer in spirit, if not actually blood.

After all, Atif Janjua still holds on to a smattering of Spanish. It is far worse than his English, which he once heard called “perfect,” though he feels that the need to use this descriptor has quashed any of its authenticity, well-intentioned though it might be. His Spanish, on the other hand, has been called “pésimo” — the worst of the worst. This is not uncharacteristically harsh, as far as María is concerned.

His first wife was a Mexican — an intractable woman who used to swear regularly at him in her native tongue. He never sees her these days, but his son Adnan has been coming with increasing frequency to visit him at the shop. On some evenings, he will close up the till and they’ll go out back for a cigarette; rather, Adnan will smoke a few while Atif Janjua hovers silently by the dumpster, wondering how to go about informing his son that this habit, although not categorically forbidden in their faith, is discouraged. How to do this without driving him further toward apostasy?

It strikes him as funny: his son crosses the water to visit him at his workplace on 15th Street, even though his mother’s home in Fremont can’t lie more than a mile away from the modest house where Atif Janjua lives with his current wife and two other children. Economical or not, he enjoys these visits. Their relationship was arrested during the boy’s childhood, but now Adnan is a man of eighteen — tall, fair, and square-jawed. His eyes and high cheekbones are lifted from the portrait of a Mughal king; perhaps he’s also the descendant of some Tarascan chieftain — who knows? The boy’s mother is from Puebla, and even used to claim a Levantine progenitor. These visits are some of the only times when Atif Janjua rejoices in the fact that he and the boy share a surname that betokens a quasi-Indian past. Were his surname Ahmed, or Khan, or Shaikh, to name a few, the boy’s provenance would be recognized only as Muslim, all other details vague. But the world will now know that Adnan Janjua is a Pakistani Rajput, or at the very least has a Pakistani Rajput progenitor. He seems invincible, appropriately warrior-like, claiming the earth that lies beneath each pace he takes in black Timberland work boots, a long thin braid of hair whipping behind him.

These are the bright points in Atif Janjua’s work week, or fortnight, perhaps — in truth, the meetings come in a non-calendrical pattern. The rest is a glacial slog; he seeks out what forms of stimulation he can. He tests his eyesight by counting the beers in the cooler opposite the cash register. The multicolored cans begin their stocked lives carefully organized by brand into straight columns and rows; but by the end of a given day, the borders will have been agitated. Six-packs will have been shuffled, Pacifico in Tecate territory, and vice versa. The machinations of the kids in the store — this is a drama he has seen staged by different groups of boys, none of whom can be older than 18. One will scour the cooler for a desirable brand. He will then lug a six- or twelve-pack nearly to the counter, before a compatriot of his says something along the lines of “Naw, ese,” or “No, puto,” and the selection process starts afresh. At the end, he will have moved all the way down from the beers to the neon-colored wine concoctions, and select one of these. (They are boys, after all.) By the end of this process, the cooler looks like a jigsaw puzzle hurled at a wall by a frustrated child. The boys undoubtedly do this to pester him, to test the limits of his patience. Little do they know that he has an almost mystical tolerances of little annoyances — that behind the counter floats a dervish of sorts. How else can someone with an MA in history from Punjab University survive in this particular life of little insults and boredoms? He will squint at the young man who places the alcohol insouciantly on the counter, unfurling the crumpled bill offered as payment. The patron scowls in a bid to add years to his appearance, but only succeeds in further deducting a few, looking like a petulant boy. All the same, there is no need for the youngster to worry; the Yemenis explicitly forbade Atif Janjua from requesting ID long ago. He received this order to risk jail time on an hourly basis with a serene look of acceptance, nothing more. After all, he is generally given free reign of the shop, and in effect can do as he pleases. He could ban the entire gaggle from the premises if he felt such a whim. But these tamashas rescue him from a few minutes of silent boredom, when he would be doing nothing other than standing around, probing the reservoirs of his molars with the apex of his tongue — and moreover, why keep money out of the till?

Atif Janjua has come to notice a direct correlation between seasonedness and politeness. On a few occasions, the cash register is approached by terrifying-looking creatures, darkly glaring, their heads patched with tattoos. He used to shudder, expecting a weapon to be brandished. But instead, inked, calloused fingers would delicately place an iced tea on the counter, or point to some smokes — and Atif Janjua would be called “sir,” and instructed to have a nice day.

On Adnan’s penultimate visit, Atif Janjua sticks his head out of the shop door to see if there is an onslaught of potential customers. Finding none, he locks the door, flipping the the plastic sign with its clock from verso to recto, but making no effort to reconfigure the hands. His son eventually swaggers into the shop wearing a large Chicago Bulls cap. He casts a bewildered look behind him as he passes through the doorway.

They convene, as usual, out back, but not before Adnan buys a pack of cigarettes. He pulls a ten dollar bill, of all places, out of his shoe.

“Putar, how much you smoking these days?” Atif Janjua asks, trying not to sound too solicitous.

“Not that much, pops. I’m cutting down.”

“That’s good, that’s good.” He is mollified, regardless of the commitment. Pops. He remembers when, on the few occasions he saw him during his childhood, the boy called him “daddy.”

They sit in silence for a while, Adnan finishing his cigarette, exhaling through his nostrils. A long commute, as though San Francisco were the mouth, San Jose the lungs, Richmond the nose. Atif Janjua thinks of the transit map and the various newcomers, all with only a tiny bit of English, whom he has helped to read it, throwing in, for their comfort, a few words of his remedial Spanish: “Buena suerte, amigo,” to a beleaguered teen in an El Salvador soccer jersey, still not seeming reassured that he had been given valid directions to the train line’s terminus.

The boy removes his insulated vest to reveal an oversized T-shirt; its hem had bunched like an accordion under the tighter outer garment. This catches Atif Janjua’s eye only because he has never seen his son in a šalwa?r and qami?z, a sleeveless waistcoat fitting smartly over the whole ensemble. A photograph of a slight youth with braids is silkscreened onto his shirtfront; it reads, “R.I.P. Droopy.”

Atif Janjua meditates for a moment on this Droopy. He then speaks. “This your friend?”

Adnan gives a start. “Huh? Oh, yeah.”

“He has become dust?” Atif Janjua doesn’t know many English euphemisms for death, and cannot bring himself to use the verb “die.” For him, people simply “go,” for the most part, or “pass.” He has never really absorbed the fact that these means of circumventing the truth — that hearts stop beating, that brains cease to function — are common to both English and his native tongue.

“Huh? Oh, yeah. Gone but not forgotten, you know.”

“You honor your friend.”

“Yeah, you know. We used to be caught up in some stuff. I’ve been trying to move forward.”

Adnan then relays some details about his new job unloading delivery trucks. “Don’t drink anything out of those cans,” he warns. “I’ve seen some nasty stuff go down, pops.” He lights another cigarette.

By the end of the conversation, Atif Janjua finds himself debating whether to make the Yemenis, or at least Ghiyath, aware of the hazards of rats scrambling across the tops of soft drink and beer cans.

Adnan wants to leave via the gate to the alleyway, so Atif Janjua unlocks it for him; he holds it open as they share a one-armed hug. He watches his son walk away and round the corner.

Out of sight, a familiar voice rings out. “Watch that ass, holmes!”

Cacophonies are not out of place on this stretch of the street; a perpetual flea market is held down the block. An elderly man, very black, is constantly bantering with people up and down the block, in a Caribbean version of Spanish that sounds strange and sympathetically out of place to Atif Janjua. There is occasionally a preacher, a Salvadoran Pentecostal of sorts; Evangelical Christianity is a mystery to him, even in English, though the threat of hellfire is one he has heard many times before (in more languages than one). There are disputes left and right. To his ears, these are all ambient noise, no different from the dawn chorus that he would sleep through every morning were he not heading to the train station. His son’s voice makes him prick up his ears for the sound of a scuffle in which he, Atif Janjua, actually has a stake of some sort. But that cry seems to have been the lone perturbation. He breathes deeply by the gate. Two young men in black hooded sweatshirts with shaven, square heads stroll past, unaware of his presence on the other side of the wrought iron. He strains to see if they have been in the shop before; if they haven’t, then the younger troublemakers, the wine cooler thespians, are their simulacra — siblings, perhaps. This pair moves with a bit more determination, but haven’t yet acquired the silent restraint of their elder brothers, the ones with India ink latticing their scalps, a sea of line drawings and inscrutable items written in Fraktur. They chuckle as they pass. “Yo, fuck your dead homeboy!” one of them yells, laughing. And that seems to be that. The time for conflict has elapsed, and cannot be renewed without a great deal of effort, a cost deemed to great, perhaps — there are after all people to see, corners to stand on, cans of beer to crack open, and all this would be delayed if they doubled back to remonstrate with Adnan. Accordingly, a few consolatory jokes can be made at the expense of poor Droopy; the words “weak-ass chapete” ring out in the alleyway. Atif Janjua walks briskly to the front of the store and sticks his head out of the door, but Adnan is no longer in sight — it is as though the insult, the disrespect to the dead, has rubbed him out, or painted over him, like a latent apostle hiding under a layer of tempera in The Last Supper.

Later that evening, when he takes a crumpled ten-dollar bill and counts out change, his hand wavers. The bald, tattooed twenty-something standing before the register does not seem to regard him any differently, but he, Atif Janjua, is newly aware of the inimical air around him, the eerie vulnerability of an empty sidewalk. On his way to the train station, he chooses the most densely populated path, weaving between parties exchanging sachets of intravenous drugs, and a pimp and a prostitute caught up in a noisy dispute.

Many days he spends his time at the register silently repeating Urdu couplets, mouthing the lines syllable by syllable. He has been to a more than a few poetry recitals in his home country. He recalls solemn, durbar-like affairs; the ša‘ir would relay the poem’s first line matter-of-factly, and then reiterate it, drawing out the words and pauses between them as though speaking to the cognitively impaired. Rapturous gasps would ensue, drowning out the pensive grunts of those few people with less conviction. As a young student, Atif Janjua rolled his eyes, and compared these couplets unfavorably to Pope, or even to the more elementary Wordsworth verses he was forced to memorize as a schoolboy, never having seen a daffodil. But the reciter’s repetitions had their effect on him, more so than his own rote learning of portions of Palgrave’s Treasury. They certainly do today.

In his mind is a couplet by Ghalib, a curious musing about mortality:

Maut ka? din mu‘ayyan hai

Ra?t-bhar ni?nd kyon nahi?n a?ti??

‘The day of death is predetermined;

Why doesn’t sleep come at night?’

He runs through it first with the usual interpretation: Silly sleep, why don’t you come? After all, the day of death is predetermined by Khuda, by God.

He then considers the more heretical reading: Sleep would come at night, if the day of death were predetermined by Khuda.

At times like this, he tends to shoo away the unorthodox thoughts that haunt him, whispered enticingly in his ear by Iblis. While his doubts are not infrequent, the mosque he attends on Fridays is a place of great social comfort, a warm, communal place. It would defy all notions of propriety to enter the building if he truly were a few steps removed from apostasy, even just in his mind.

Before his son’s last visit, Atif Janjua industriously readies the shop for his arrival. Seeing a few day laborers approach the door as he is flipping the sign, he surprises himself by gruffly snapping, “Closed!” and shepherding them down the sidewalk with his glare. He puts some cash in the till and tugs a pack of cigarettes out of the rows against the wall, realizing, as he tentatively loosens it from the grip of its neighbors, that he has forgotten his son’s preferred brand. He knows, or thought he knew, the choices of others: he has come to associate Newports with a few black faces, Pall Malls with wizened old men, Kools with Chicano youths, and Parliaments with the young, carefree-acting whites in which he is beginning to see an uptick. He pushes the pack (Pall Mall) back in. “Adnan don’t like that one,” he says softly. He pictures himself at the mosque, fetching a plate of food for his son during the Friday meal, saying, “Put more nihari; Adnan likes.” His fingers do a tarantella over to the Camel Lights. Who isn’t fond of Joe Camel, suave dromedary that he is? He recalls the cartoon mascot from before its obsolescence.

When Adnan arrives, Atif Janjua gestures graciously toward the pack. The boy has come to the front door, looking confused to find the shop and surrounding area empty. He takes a cigarette desultorily, but exercises care in refolding the foil-covered paper under the pack’s lid, as though attempting to close an umbrella as economically as possible. Like always, though, one fold too many is subsumed in the tangle of paper, and the pack’s lid buckles over the groaning, fat mass.

Out back, the boy fidgets on the step, manipulating the cigarette like a drumstick, until he is reminded with a furtive gesture from his father to light and smoke it. They have remained silent for the most part. Atif Janjua feels himself, from time to time, moving to ask about work, friends, or family, but stops himself on each occasion — he is too ignorant of these aspects of Adnan’s life to even sketch out a well-grounded, meaningful question pertaining to any one of them. He cannot be sure that the boy still has the job. At their previous meeting, he seemed passionate about the work he did, but vigor of this sort is easily exhausted — who could know this better than Atif Janjua?

“You ever feel like,” Adnan muses, pausing to doff his cap and put it on backwards so smoke isn’t trapped under the bill, “like some things you can’t really shake?” His fingers keep scrambling to his shoulders and head; the fabric of his cap purrs as his fingernails streak over it.

“I don’t know, son.” Atif Janjua feels that at times, it is all too easy to forget one’s origins. He’s had to remind himself each day of the weight, the anchor, the fetters that tie him to faith and homeland. Daily, he delivers many pinches to himself, to shake himself out of each reverie that washes over him, each time he feels himself drifting into a new life, away from his inborn tendencies. The two years he lived with María were a protracted dream sequence, a boat journey across a black lake. Junu?n, there is a word for it, ubiquitous in ghazals and film songs — a state of possession by a djinn. In the end, he had to revive himself, and return to Islam, to the old Punjabi manners, to the habits of people with names like Atif Janjua; he could not alter her ways, but more critically, he was too stubborn to permit her to make changes to him, however great their utility might be.

“Some say, the fate is written on the forehead.”

At home, Atif Janjua marvels at the cordon between his domestic life and the rest of his day. At work, the feel is grimy and sinister. The only predictable thing is the handing over of cash, and even this is not a constant: now and then, a story will trickle over from a neighboring store of a blade being brandished at the register, or someone attempting to shoplift. These are generally desperate, unsuccessful acts — the sort of thing that makes you want to make a gift to the pathetic culprit, were it not expressly forbidden by the Yemenis.

His home seems parsecs away. It is white of ceiling and carpet, with some green and pink wall hangings (he has never been one for decorations); a tapestry emblazoned with the šahadah hangs in the living room. It smells of fennel seeds and South Asian dry goods, of sautéed cumin and saffron. There are Hasan and Maryam sitting cross-legged and shoeless on the carpet, his wife bringing him his food before overseeing the children’s homework. He often falls asleep in his immense chair before he can finish the Urdu newspaper, having already thumbed through the Chronicle, and perhaps even the Tribune, if he’s feeling sufficiently unmoored, detached from his domestic surroundings. His abode is immensely comfortable, if a bit dull. Save for the carpet, it’s not much unlike his childhood home in Lahore, though back home, the noise of the street would always penetrate the riot-proof fortification that surrounded the house, and on this cul-de-sac, the silence is disturbed only periodically by a car pulling into or out of a driveway.

One evening, the ringing of the telephone truncates the odd dream he is having in his chair. Bushra picks it up. “Hello.” Her tone of voice is a warning that the caller’s words, unless uttered with care, may be lost on her. He can hear the muffled strains through the receiver’s earpiece.

She brings the receiver over, her face disapproving, but tinged with concern. He takes it from her. “Hello?” comes the plaintive voice over the line. “Atíf?” Not even twenty years, and she has forgotten how to pronounce his name.

María. He lets her continue. “Oh, Atíf. Something terrible! Lo asesinaron … on the street, like animals!” He can hear her convulse on the other end, her sobs so intense they come in silence, punctuated only by the sound of air strong-arming its way through the windpipe.

“I’ll come,” he says. The shooting took place at a gas station a mile away.

The cold hits Atif Janjua as he gets out of the car; he hasn’t changed out of his qami?z, and hasn’t put anything on over it. The air is dry. Imagine the loneliness, he thinks, as you lay on the hard ground, waiting for an ambulance, slowly casting aside the various benefits of clinging to life, like petals of a flower losing its luster. Another boy had been slain alongside his son. He wonders if Adnan took comfort in his friend’s company as he lay dying.

María runs to him, sobbing. Forgetting the tragedy for an instant, he notices what has changed about her in the past two decades, and what has stayed the same. He gives her a gentle, consolatory hug, but can feel nothing, apart from the cold. Many conflicted thoughts and memories, agitated specters, race at him all at once.

A thirty-something Latino cop with a crew cut approaches him. “You one of the boys’ fathers?” He gives off an impatient energy. There are no doubt many distractions. In her grief, María seems to be losing her English, and her Spanish is as hard to decipher through the tears and mucus. The policeman undertakes to fill in some of the details.

The two boys had been on their way to some place, likely a party, when they stopped to get gas. That much is clear: the rest of Officer Huerta’s account is too circumlocutory, too tentative, too hushed to mean much to Atif Janjua. “We were called to the scene with a report of a gunfire incident involving two victims which took place in the parking lot. Both were pronounced dead at the scene by the paramedics.” Everything seems coated in some strange, bureaucratic, fire-retardant substance. No inference can be drawn too hastily, no matter how reasonable. He looks at Atif Janjua for a moment, his mouth open, as if wondering where he fits in all these lives.

“We are investigating a possible gang link,” he notes, before trailing off. Perhaps, in his exasperation, he has decided that the history of the rivalry is neither relevant nor something that Atif Janjua can truly comprehend, though his own flesh and blood has just been cut down by it, and despite the fact that a faction of this militia treats the shop where he works as its army camp, or mess hall, or PX. But that’s not quite it: he seems to be stopping himself from being too candid, from acknowledging that real danger lurks in this anonymous suburban wilderness. “Looks like the perps passed by here in a car, and then circled back around the block … opened fire on the victims while they were waiting beside the car, pumping gas.”

Outside, the air, getting chiller. The pang of of that anonymity, the uncurious darkness. A breeze here and there, but only a gust — nothing to carry a message, a plaintive moan across a slab of earth.

Within, sick intoxicating warmth: a broth churning violently, filling your insides, then flowing out, basting you.

A boyhood vignette, long past. He had been taken for the summer out of Lahore, to his village, in the flats near the Salt Range. Like a Sufi qalandar he had spent the days divagating, on paths raying out from the courtyard, with its hens and drying grain. The sun maddening, a great mustard flower. Past the fields, the terrain craggier, all gray rock, tough-looking greenery holding its own in the cracks. The call of a bird piercing the silence had drawn his attention, and he tripped, and collapsed like an accordion against the earth. In the dimming light of five in the evening, he could make out his calf bone.

Night had fallen as he lay there, too debilitated to shiver, his trouser leg wet with blood. His tongue felt brittle against the roof of his mouth. He thought not of water, but of his favorite sweets. An eternity of silence, broken up by the ghostly sounds of the countryside at night. A cuckoo far off, koyil, koyil. Some other creature scratching out of sight.

The compacted scuff of horses’ hoofs on the ground. Normally, this betokened banditry, but he could not flee. Cloaked figures stood over him, musing quietly, agreeing silently. And he, a patient, patient. Surrendering his agency to the forces around him. He found himself laid across the saddle — before he could shut his eyes, and reach that place that knew no enmity.

Atif Janjua attends the funeral alone. At home, he can sense Bushra’s vacillation over whether to offer to share his grief — not sure she could fully understand its intricacies — and whether or not loss is different in this world apart that he partially inhabited before she knew him. He simply holds her arm reassuringly, and she continues with the domestic regularity that is his sole comfort during the days after the phone call.

He has never been to a Catholic church. He mills around dejectedly; no one speaks to him but to say, “Hello.” English is a strange middle ground; he feels that he is more comfortable in it, more willing to traffic in it, than these people are. Were he among whites, he realizes — thinking of some of his neighbors, well-meaning, comfortable-looking people — that he might find himself the object of some mission born of a perceived obligation to minister to the needs of an outsider. But such a flavor of solicitude is a luxury, one not available to the people present here. This is a relief: he is spared the burden of confirming someone’s expectations. That, in fact, he is unhappy, out of place, antisocial, and incapable of being helped — that he’s not at all too proud to grasp a hand extended to him in a time of uncertainty, but in reality too benighted. An unworthy interloper.

He practically sleeps through the eulogy, of which he can’t comprehend a word. Afterwards, he spends much of his time gazing into the coffin. The boy was shot several times, but only in the torso, and thus the casket can remain open. The face looks serene. He thinks it evokes the face of the emperor Humayun. But the Mughal, they say, died when, upon hearing the muezzin’s call, he automatically knelt to pray on a step of the staircase he was descending, lost his balance, and fell to his death — not from gunshots outside some ratty gas station. And the son of Babur had been laid to rest in a giant tomb in Delhi, not interred in a Catholic cemetery in the East Bay where the grave markers read “López” and “Pérez.”

They keep him apprised of the case. It progresses rapidly. The suspects live a less than a mile from the scene of the murder, and the car and weapons were easy enough to find. A chance occurrence, they went for a drive and sighted a potential target. Amazing: some of these people can probably not read properly (apart from the letters S and N, never mind E and W), yet they can pick out an enemy in a poorly lit parking lot from the way he wore his hair, his clothing, a glimpse of the tattoos that for anyone else are like devious hieroglyphics to decode. Just as he can identify a Sunni convert from Shiism by the way his hands twitch when he prays.

After the funeral, he tries to restore his life’s tentative normalcy. He returns to the shop without any time off — he hasn’t even told the Yemenis that there was a tragedy. (Familial loss is an odd, negative-sum game in their family; he knows that Wathiq, one of the many brothers, is currently in jail for firing a gun at one of his current employers, Ghiyath, in a fit of sibling rivalry.) His hand is starting to quiver less when he accepts a bill from a blue-clad 18-year-old. Why tremble? Everything is the will of Khuda.

However, the tragedy is renewed for Atif Janjua when he opens a newspaper and inadvertently reads some of the coverage. Not only do they describe his son as a “person with gang affiliation,” but the paper identifies him as “Anand Janjua.” Thus is his son made a Hindu Norteño in death.

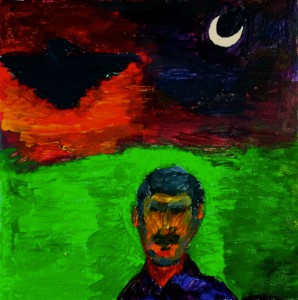

![]()

Chundra Aroor is a researcher in linguistics at Lund University. He lives in Dalby, Sweden.

Chundra Aroor is a researcher in linguistics at Lund University. He lives in Dalby, Sweden.