The Untaken Frame

Ricky Toledano

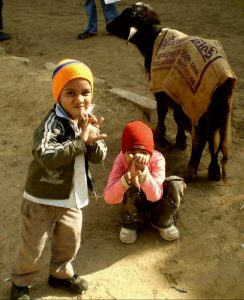

It was the picture I chose not to take: that of a little girl walking on a make-shift, not-so-tight rope, two meters above the ground. Swinging to the music while standing on the rope, I expect her to tumble downwards in a frightful break dance, but she balances with a cane of bamboo as if motionless, completely secure, even when ticking through the air from side to side as the fastest of pendulums. It is a feat so incredible that I order our car to halt as our necks crane backward not to lose sight of her out of the grimy window. We had almost arrived at our destination in the Old City and could easily walk the rest of the way, so I simply had to see the street-side act and contribute to the money pot placed on the dusty ground, just below what seems to me to be a flying six-year-old with the fluttering poise of a hummingbird.

When we get out of the car, her swinging stops and she is already walking backwards on the rope and then forwards, artfully stepping a bicycle tire frame across the rope, as if she were cycling. Like antenna on each side of her head, I am quite certain the black braids of her pigtails help her balance, much like her bamboo cane. Her face appears absent in concentration, but it is hard to see her behind the oversized sunglasses and sequin-studded ball cap that is also too big for her head, shading her face in the bright, midday light. Her t-shirt and jeans do not have the same theatrically smart attitude of her hat; they are very grubby, just like her little chapped feet, which are all that attach her to a perilous world in her act of balance.

“They are doing this for food, bhai. Let’s help them,” said my friend, leaning into my ear among the crowd we have already joined. His prompt was unnecessary; I had already been digging in my pocket for my wallet, while awestruck by her performance. My dropped jaw surprised my friend, “You mean to tell me you’ve never seen this before?”

“Never! I’ve never seen anything like this before—anywhere!”

“But they also have them in Delhi. You’ve never seen them in Chandni Chowk on Sundays?” He asked me, incredulous.

The girl’s instructor must be a teen-age relative, who is just as casually dressed as she is, except that he wears a Muslim taqiyah . There is another, older youth standing in full white kurta-pajama and skull cap, operating what we called in my day a boom box. Changing songs for the little girl’s acts, the starkness of his white dress against the backdrop canvass of cement and terra cotta would also have been a handsome photograph, but nothing like the spectacle of the little girl, who at such a very young age has an astounding control of breath, mind and body that every motorcycle passing by stops and leans over to drop coins into the pot. On the other side of the street, a small crowd of all ages has gathered, from which I take my turn to shyly dash across the busy lane between breaks in the cars and motorbikes to deposit money in the pot.

It is impossible that she can concentrate with all this movement around her! I think. Not for the most split of seconds could she allow her concentration to quiver, hearing the sounds of the coins in the pot, much less seeing who dropped money or how much. Her mind must not follow the eagles soaring overhead; the wafts of rose, chandan and urine; the little cows meandering the street; the children giggling. Much less could she have noticed the curious firangi, dressed in light-blue kurta, jumping from a car to take her picture.

Firmly retaining her senses, her attention is impenetrable. At such a young age she has already conquered more mastery of body, breath and mind than I will ever have, even after years of practicing yoga—if, that is, that is all that is meant to be accomplished by yoga.

It isn’t. Or the discipline of every gymnast or athlete would be all that is needed to be the greatest of souls.

And that is why the spectacle was a delightfully humbling reminder of how everyone is born not only with their own unseen challenges, but with the tools to overcome them. It also produced another inevitable yet unspeakable thought: What if she falls?

“These kids are all over India, bhai. They have so much talent! I wish I could take them all, have them trained professionally. No one could stop them! They would fly!”

“Just like you, bhai?” I smiled, arriving at our destination after having spied the old lanes, already guessing in which one to hunt for the homemade halwa and bhujia that has been disappearing as customers have opted for gleaming packaged goods to eat away from the old cities of India. For someone planning as eagerly as my friend is to fly away to the US and leave his country, I am lucky that he still has the nostalgia for the old India of his childhood, because it is a taste we both share. He had also rejected shopping malls and foods packaged like pharmaceuticals long ago—and he taught me how to navigate confusing streets well. Teaching me pursuit the old way, I learned to use my nose, instinct and espionage, watching where people conglomerate and what they carry on the busy streets. We look like two mongooses hunting on the sly; very little can escape our desires in a traditional bazaar.

“You don’t want me to go to the US,” he countered.

“No! Of course not! It is an opportunity you cannot refuse. What I don’t want is for you to think you are going to some place better,” I retorted, never losing the opportunity to remind him that my country is not the paradise he imagines; whereas my young friend doubts there could be anything displeasing in the world’s richest and most powerful nation, a place without the street-side circus acts, a place where everything works.

Or so he thinks.

I sucked my teeth as I tried to find where to begin to offer an explanation – if I even had one – while sitting in a very humble restaurant of walls less white than the white butter it served with bajra roti on reasonably clean thalis with the hottest of catnis.

In the lane, an old woman set up her cart to sell traditional clay diyas. Monkeys prowled across wires to follow a vendor of carrots, radishes and bananas. A policeman talked to boys on motorbikes in the shadows brightened by the vivid colours of a sari shop. People spoke loudly, in a volume and tone that Americans might mistake for hostility in the absence of smiles, but there seemed to be a shy exchange of laughter among pedestrians who looked and talked to each other. Everywhere you glanced, the faces were those of contentment or unmasked emotions. No one was alone, because everyone looked at everyone, everywhere – their eyes connecting with either formality or familiarity, as if the simple act of walking the street was conspiring in a game together.

The exchanges could be repeated in more than one country I know, including Brazil, my home for more than twenty years, but it was one that cannot be found in the US—something that would have been very difficult to explain until I turned my head around to call the waiter.

It was a natural gesture to have my eyes meet those of other patrons who also took advantage of my movement to see mine. And it was in the serendipity of looking into strangers’ eyes that I realized I might be able to offer an explanation to my younger friend.

“When I was growing up, I remember looking at everyone on the subway and no one ever looking back. I remember clearly thinking that something was wrong; it was impossible that people couldn’t see me. I saw all of them.”

“What are you talking about?” he snapped.

“You’ll see when you arrive there. They pretend not to see each other. It is hard for me to describe and for you to imagine, but they don’t look at each other; they avoid touching one another; they keep a distance, maintaining a ring of privacy. You will feel it immediately: no one will look at you, but everyone will see you and move out of your way. It is the one thing I find nerve-racking whenever I go back.”

“Hmmm,” sighed my friend, whose list of nerve-racking gestures was composed of the opposite: the way his fellow countrymen always bumped into him or cut him off without any regard. Sitting on the other side of the table, he was trying to imagine a world on the other side of the planet, a place of opportunities he feels he doesn’t have in his homeland; a place where people respect the rights of others; a place where individuals actually have rights. It is a place, he imagines, where everything is safe, clean, beautiful and organized.

Or so he thinks.

It is everything he wants. But it is also a place where people are not only walking around with walls around them, they are building real walls, barricades that are far uglier and more pernicious than the ancient remnants of the walled city around us, with its great barriers that had been built and rebuilt over the centuries, more times than there were cups on our thalis. The separation of space may be the futile endeavour of mankind since time immemorial, erecting dividers to keep the undesirables out, but I have the opposite impression while walking the streets of the Old City: the remnants of those ancient walls seem to stand unsuccessfully to hide people in, especially people like the flying family circus troupe.

“I sat next to a Punjabi man on a plane. He was an immigrant to the US; he had lived there many more years than I ever had. He owned a petrol station and raised a family there. He is probably the man who you want to be some day. He had dealt with all the prejudice against him over the years: the rejections; his children bullied; the police that refused to help him when his business was robbed. He told me something I will never forget: ‘America is a funny place: the rich aren’t happy; the poor aren’t happy; nobody is happy. They are so aggressive. It’s like there is no love in their hearts’. Naturally it was a gross generalization, but it struck me. Somehow I knew exactly what he was talking about – which might say even more about a place like your country than mine.”

“Which is also a gross generalization!” he retorted.

I swallowed cchaacch, not only with cumin seeds but with the seeds of a thought: I suppose that is the risk of a photograph, capturing people within the four limits of a frame. In contemplation, my mind wandered sinuously back down the road to the picture I didn’t take, refusing to frame the little performer.

Pausing before comically raising my voice with authority to imitate the patriarch of his family, I aimed my finger right between his eyes, “Now you listen to me young man…” My friend smiled, almost spitting his water before receiving the sermon: “I will miss you. Please remember that you may travel to the other side of the world, you may try to run to the corners of this universe, but you will never escape from yourself. We take ourselves wherever we go, together with all our personal demons. There is no place to run and hide and there is nothing we can consume to make us happy, to make us complete. We are already complete. This is the message of the very Upanishads, and it is said that it is the very mission of life to realize that there is nothing missing.”

Falling silent and looking away from me and at the people around us in the neighboring tables, it was his turn to suck his teeth and think. The sermon had hit its target, but he is a clever and agile young man who was not about to let me get away with lecturing him with wisdom easier said than done. He returned to me, sharply and in the ambush of analogy, “So, according to you, there is ‘nothing missing’ from that little girl’s life?”

“I’m sure there are many things,” I swallowed, “But I am also sure her concentration on what she has—and not what she doesn’t have—will always make her wealthier than people like us, who always need more—catni—to be happy.” I slurped the delicacy from my fingers, “I will ask for more.”

After having consumed more sugar and salt in one day than I am capable of in one month, it was in the evening that my friend’s mother made me a gallon of nimbu pani with neither of the white poisons to wash away my sins. I was more than satiated by the spoils of a day in the Old City, but not by its visions, which I unpacked during my silent time as the sun went down. In my mind, I revisited the little girl on the rope, looking at her through the black frame of my lens, remembering how it was not only difficult to find a harmonizing angle for a moving subject, but that there was something disturbing about confining her within the limitation of four borders without knowing anything about her story. It would be committing a kind of insincerity. A real photographer cannot vacillate like that.

But what had really stopped me from pulling the trigger, placing my camera back in its holster, forfeiting what might have been that perfect shot, a time capsule, was a sensation similar to that which occurs just before picking a flower, when doubt shades the choice to possess beauty by destroying it. My forbearance had also become my own balancing act: I was also walking a rope, one I have fallen off many times in my life when choosing between capturing an object and learning to let it go.

There was more beauty in beholding a picture of her that had no frame, a portrait of duality: the individual that is at the same time limited and limitless. She blended into a seamless world around her in every direction, from the cerulean infinity above her to the road below her, which could even lead me home, across the world. Then, there were the walls.

Walls do not separate space; they exist in space; therefore, they separate nothing. I contemplated the Vedic maxim that had first sent me to India with more than just an intellectual curiosity so many years ago. They were the words pronounced in just the right moment that changed my trajectory, leading me into the unimagined direction of studying Vedanta, an interest not at all shared by my friend, an engineer who might even be too intelligent for his own good, the way he hastily sought holes in arguments, even ones not fully comprehended.

About to embark for the US, he was more interested in the tradition of many other Indians who have gone abroad than on the Tradition—a body of knowledge for which he had no use. Regardless, I delivered the words of wisdom, even if clumsily over lunch, because much as I had chosen another culture, extending a cord ambitiously far from home, I saw my friend was already high above, starting on that familiar, treacherous rope. That is why I ran to pad the ground below him with words, so that they would be there for him to cushion the inevitable falls that land us the disappointments needed to comprehend that happiness cannot be acquired; it can only be revealed, because it is not a place at the end of a rope; it is located in a place so close one can’t see it; it is a place that isn’t a place.

And just like my friend, I am quite certain the frame of a photograph would no more define the little girl any more than walls will contain her in the future. She will jump them. I won’t be there to applaud that day in her life, the way we did standing at the roadside, but I know she will do it, after learning all there is to know about rules before breaking them, like studying gravity to learn to fly.

That is when I opened my eyes, returning to the day’s last beams of light around me, and not those that glimmer in my head. I smiled as I could not help but contemplate that I might break an old rule upon discovering its opposite: it may very well be that a few words are worth a thousand pictures.

![]()

Originally from Chicago, Ricky Toledano lives in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where he has worked as an English-Spanish-Portuguese translator and English language instructor for over twenty years. He is the translator of Padma Shri award-winning author and Vedanta teacher Gloria Arieira’s the Bhagavadgita (Motilal Banarsidass). He is the creator and curator of the multi-lingual platform for the humanities, amultiplicity.com.