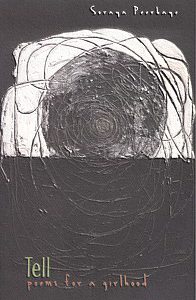

Tell: Poems for a Girlhood by Soraya Peerbaye

Reviewed by Bakul Banerjee

Soraya Peerbaye is a Canadian poet currently living in Toronto. Tell: Poems for Girlhood, her second collection of poems, received the Trillium Book Award and was shortlisted for the prestigious Griffin Prize for Poetry, awarded to Canadian poets. Her first collection of poetry, Poems for the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (Goose Lane Editions, 2009), was nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award.

On my first reading of the more than one hundred pages of “Tell: Poems for Girlhood” published by the Canadian publisher, Pedlar Press, I could not help but be drawn to the masterful techniques the poet employed to tell the story of a horrific murder in 1997 of Reena Virk, a dark-skinned girl of South Asian descent. While Peerbaye tells the story of the crime, she plays with the alternate meaning of the word “tell.” As she explains in the poem Tillium Bridge (p 83), tell is derived from Arabic, and also means an artificial hill formed by refuse from ancient settlements, often invaluable to archaeologists. Like an archaeologist, Peerbaye chronicles the evidence, presenting it against the background of sterile judicial proceedings and the landscape surrounding Saanich in British Columbia, Canada. The poet unravels the tangled threads of racism, teen angst, and the yearning to be accepted. On a personal level, she explores what it feels like to live in a space of veiled rejections where identities are often trashed.

The book is laid out in five sections, each interspersed with testimonial scripts. The first section, titled “Search,” explains the search for the dead body and possible causes of death. The location of the crime, which occurred at A Pleine Gorge, the Craigflower Bridge, and the marshy river, is the subject for the next section. The geology and mythology of the space and the pathology of the drowned body are depicted with remarkable detail and clarity.

The poet describes what the girl might have seen:

“She drowns looking up, so that she sees her assailant through the water. Face blurred, but the hands clear.”

The back-story of the bold teenager and people surrounding her is presented in the section “Who You Were.” In the poem “Nothing, Nothing,” the poet describes in the girl’s own voice what it feels like to be different:

“Girls encircling me, chiming as they queried the beauty traits of the women of my country.

Elusive silver smiles, shifting from face to face, too close.”

The centerpiece of the section “Tell” is about multiple trials. As suggested by the section title, it contains a significant number of excerpts from trial transcripts. Several poems are built on evidence gathered near the Craigflower Bridge.

The last section, “Landscape without her,” is my favorite one, is probably the most lyrical. Possible motives for the torture and murder are enumerated here. Peerbaye takes full advantage of a rich motif from the victim’s Indian heritage to create an evocative image. She uses the moon-shaped cigarette burn on the victim’s forehead to the placement of a bindi, the traditional colorful dot. It is reduced to a branding ritual of permanent rejection carried out by the torturers, seven local teenagers, five of whom were white.

If read sequentially, Tell emulates a crime novel. Raw materials used by the poet are actual trial records spanning twelve long years of multiple trial investigations. That Peerbaye was apparently close to the victim and attended the trials occasionally and this personal engagement is evident throughout.

Most of the individual poems are marked with clever use of trial transcripts, contemporary events like the appearance of a satellite, and metaphors culled from diasporic histories and ancient myths of the region. Occasional poems about the author’s own life and how she reacts to the incident provide interesting insights about the people around Reena Virk. Reading the book backwards section by section, as I often do with poetry, I am impressed by the consistency of the story telling style. Most poems are in free verse, but some are prose poems. I cannot imagine any other format that would have worked so well. The result is an uncommonly meaningful collection.

As I savor the book page by page, often flipping through it randomly, the obvious question is never far from my mind. Who will read it? This book has a universal appeal because it deals with an intensely personal narrative of the murdered child set in the country of Canada, a country alien to her. It is also steeped in metaphor and rooted in immigrant experiences that still haunt generations twice removed. This is a story about the search for acceptance, immigrant experience, and alienation. It should appeal to everyone wishing to patch the ragged holes in the human psyche. It is certainly a must-read for both aspiring and experienced poets of the South Asian diaspora as they attempt to tell their own stories.

![]()

Dr. Bakul Banerjee published her first volume of poems, Synchronicity: Poems, in 2010. Her poems, essays, and stories have appeared in many different literary magazines both in the United States and in India. She has been featured at several poetry readings and presented poetry workshops. Bakul received her Ph.D. degree from The Johns Hopkins University, Maryland and worked as a scientist at facilities operated by the US Department of Energy.

Dr. Bakul Banerjee published her first volume of poems, Synchronicity: Poems, in 2010. Her poems, essays, and stories have appeared in many different literary magazines both in the United States and in India. She has been featured at several poetry readings and presented poetry workshops. Bakul received her Ph.D. degree from The Johns Hopkins University, Maryland and worked as a scientist at facilities operated by the US Department of Energy.