“I am a die-hard romantic, unabashedly indulging in childhood memories”, says Dr. Santosh Bakaya, Poet, Author of ‘Where Are The Lilacs?’

Interviewing Dr. Santosh Bakaya, Author of Where Are The Lilacs, a collection of poems on restoring peace and harmony.

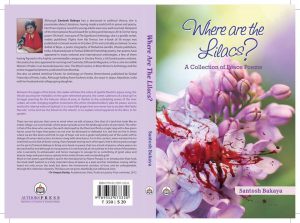

With her stupendous poetic treatise Ballad of Bapu (published by Vitasta, 2015) on the life and times of the father of the nation and the advocate of the non-violence movement, Mahatma Gandhi, which is an effervescent poetic treat to even those who have not been Gandhiji’s staunch devotees/followers, Dr. Santosh Bakaya’s foray in the literary arena of Indian writing in English has not been any less phenomenal. I was introduced to her brilliant, evocative body of work through The Significant League, a vibrant literature group in Facebook from where she had received the International Reuel Prize for Writing and Literature in 2014, and have been humbled to know the silken flow of her words that meander like a never-ending cascade, with effortless ease in both prose and poetry. Where Are The Lilacs, another one of her notable poetry collections published by Authorspress in 2016, following the success of the critically acclaimed Ballad of Bapu is like a never-ending corridor where the birds of peace fly unabashed, challenging and enquiring the essence of the crushing reality of hate and devastation all around. Up, close and personal with the author, we get to know the spirited, erudite soul giving birth to this classic collection. We get to know what inspired her to write the poems of Where Are the Lilacs and what exactly defines the versatile body of her work. Dr. Santosh Bakaya is also the celebrated author of Flights From My Terrace, a collection of 58 evocative, soul-nourishing personal essays, published by Authorspress in early 2017.

Lopa Banerjee: Dr. Bakaya, so nice to connect with you! After your phenomenal book Ballad of Bapu, the poetic treatise on the political and personal life of Mahatma Gandhi, Where Are The Lilacs, your collection of one hundred and eleven peace poems is making waves in the literary arena. What is your inspiration behind choosing these subjects for your literary work, whether it is the deep-rooted political philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi, or the poems of Where Are the Lilacs where you are a lyrical advocate of peace amid a savage, all-pervading landscape of cruelty?

Santosh Bakaya: Well, I have time and again reiterated that humanity cannot do without the principles that Gandhi stood for – Truth, non-violence and peace.

Martin Luther King Jr, had prophetically maintained, “Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of civilizations are written the pathetic words,’ too late’.” Indeed, it is high time, that we chose between peaceful coexistence and violent co-annihilation.

Let not that tide in the affairs of man ebb, let us seize it at the opportune moment. And the opportune moment is now. Or never.

‘For poetry makes nothing happen’ Thus wrote W. H Auden in his poem, ‘In memory of W. B Yeats’ – yes, but through poetry, poets can vent their ire and frustration at a world gone awry – where children die just like that! We have reached the stage where we have already started ringing our hands in impotent rage and muttering, “Too late, too late.”

I have always advocated peace, be it in my classes, or through my words. The all-pervasive cruelty, where humans are killing each other with a cannibalistic glee is so nightmarish.

Through this collection of peace poems, I have tried to emphasize, ‘the fierce urgency of now’. I have always raised my voice against injustice in any form and staunchly echoed King’s words that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”, and through my writings will hopefully continue to do so.

Lopa Banerjee: What is the significance of the title of the collection, Where Are The Lilacs? What, according to you, are the Lilacs, hidden under the blanketed coat of the ‘bloody mess’ and ‘the discordant notes of the war drums’ which you have elucidated in the foreword/Author’s Note? Would you define the poems only as your reflections on the myriad ‘peace notes scattered around us’, which you mention in your Author’s note, or do you think in the hands of a sensitive, discerning reader, they would also serve as an antidote to the anguish and despair that destruction brings along with it?

Santosh Bakaya: Well, the title of my book has been taken from Pablo Neruda’s heart – wrenching poem, “I’m explaining a few things”, where he talks of his beautiful house, bursting with geraniums in every cranny. This house of flowers was reduced to a ‘dead house’ in the aftermath of the Spanish civil war when the profusion of flowers in the garden disappeared, and the poet was left exclaiming, “come and see the blood in the streets”.

Some of these poems I wrote, while gruesome scenes flashed on the television screen, some are cathartic endeavors, and others are prayers. I cherish the hope that one day, ‘the longed for tidal wave of justice’ will sweep away all violence and injustice from this world.

When I write, my heart takes over, and my head sits pillion. Yes, there are myriad peace notes scattered all around us, but we are so obsessed with so many meaningless pursuits that we just don’t have the time to string these notes to create a soothing peace song.

When I have recited my peace poems, I have seen people crying, and commenting about the futility of violence. When will all this end? They ask. Yes, it does serve as an antidote to the anguish and despair that destruction brings, but I feel, that if I can awaken people to the ‘fierce urgency of now’, my task will be done.

Lopa Banerjee: In the very first poem of the collection, you write: “Ah, soft, the delectable petrichor/Wafts from the rain-drenched earth./In this birth is lost the stench of gore.” There is a very sweet lyrical flow in the poem which brings in the torrents of rain, ripping ‘the skies apart’. Then again, in the poem ‘The Moon Hums A Peace Song’, you present the moon as a corollary to this image of the rain, both being lingering metaphors washing away the insanity of bloodshed all around us. Would you say these poems are representative of the romantic poet within you who ushers in childhood fantasies to ward off the senseless demonstration of violence around us?

Santosh Bakaya: Yes, they are escapist metaphors for me. Nature is always soothing, the moon, the sun, the stars are indeed an antidote to the insensate violence all around. Just as an infant’s thumb creeps into its mouth, when it wants to be soothed, similarly, I rush to these metaphors of nature. They instantly soothe me.

Yes, I am a die-hard romantic, unabashedly indulging in these childhood memories. Many are the times, when the moon, walking the night in its silver sheen, has quelled the stormy turbulence in my heart and the twittering birds have silenced the churning and burning of the heart. Nature is my haven I scurry into, when confronted with the senseless violence around.

Lopa Banerjee: The poems that follow carry the delicate lyrical images of ‘love birds’, ‘chirping and twittering’, the mermaid and the dolphins frolicking and traipsing by, ‘the chubby five-year-old’ boy clapping with ‘juvenile laughter’ to the mellifluous symphony of the rain, the blue balloon, ‘bloating with promise.’ How indispensable have these lyrical images been in the crafting of these poems?

Santosh Bakaya: All these images are very important – they are not merely images but scenes which I have witnessed in the lanes, bylanes and thoroughfares of life. I can never erase the memory of that rag picker child, from my memory, who was chasing a bloated, blue balloon, his face sheathed in happiness, so pure, that it brought a deluge of tears. Small pleasures of life have the potential to make us happy, why hanker after material trinkets?

Lopa Banerjee: The poems also seem to carry a very nostalgic air, along with a romantic refrain, which I sense, has come from your ineffable attachment with the natural landscape of Kashmir, your hometown and your childhood haven. For example, in the poem, ‘And The Fires Burned’, there are some lyrical associations of a young girl with the river Lidder, the boulder, the pine tree, the hyacinths and the nameless other flowers, as she reflects sadly on her father’s tragic demise. Again, in the poem ‘Magic Of The Peaceful Past’, you write: “Changing colour like autumn leaves/Floating around like snowflakes…” How has your association with the physical and emotional landscape of Kashmir shaped up a part of this collection? Would you say these delicately woven poems can also be virtual messengers of peace in the volatile reality that your hometown is facing for some years now?

Santosh Bakaya: Yes, the condition of my hometown, known for its communal harmony, for its spectacular beauty, for the poetry of Lal Ded and Habba Khatoon, and for its Sufi saints, is pathetic right now, and no one seems to be bothered.

I was not born in Kashmir, but we spent a lot of our childhood days there. I keep going back, to find myself cavorting next to the pines, inhaling the fragrance of the poplar- lined boulevard and watching the Lidder, the pebbles making love to the waves, and shepherds singing songs of peace. My heart bleeds. It bleeds for my hometown that is Kashmir.

Yes, it bleeds through my poems.

I don’t know, whether my poems can be virtual messengers of peace in the volatile reality, but, yes, I am known to cling to straws and maybe someday, I will think that one day, I “did something slightly unusual.”

Lopa Banerjee: In your poem ‘Woman of Substance’, you write about Rosa Parks, the famous American civil rights activist and her daring defiance that pierced through the mindless segregation of a racist America. Any particular reason why you chose to include this poem in the collection? Is it because you opted to extend your voice towards any kind of social injustice that has shaken the core values of a world besotted with inequality and intolerance?

Santosh Bakaya: My all-time favourite quote is the one by Martin Luther King Jr: “A threat to justice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In this anthology, I have tried to include poems, which talk of injustice. By refusing to stand up in the segregated bus, to make place for a white passenger, Rosa Parks, on 1 December, 1955, stood up not only for her beleaguered community but for the entire human race. She stood up for peace and equality. Her one brave step created a revolutionary storm in the world.

Peace means inequality, intolerance, fairness and justice.

Call me naïve, but I earnestly cherish the hope that maybe “someday, “in the deserts of the heart”, the healing fountain might start?

Lopa Banerjee: The poems of the collection are evocative enough to compel the readers to look back at the tragic moments of loss and devastation, while also taking in a fistful of hope and happiness that comes with the closure and the catharsis that humanity derives from the warfare. For example, in the poem, ‘The Colours of Love’, the “two sparrows appear/Hopping cheerily on the branch of a dead tree”….and then “The two lovebirds fly away/To the golden gates of their paradise…To awaken the next dawn.” Also, in the final poem of the collection, ‘A New Year Dawns’, you write about the soft, soothing radiance of the euphoric dance of a new dawn, a new year. What has inspired you to portray these binary feelings of reflecting the dark and miserable, and also the lullaby-like, wistful, hopeful poems, that fit so well into this poetic narrative of peace?

Santosh Bakaya: In this topsy – turvy world, the good, bad, the ugly all go together. There is pain, devastation, selfishness, and there is also love. Being a die-hard optimist, I staunchly believe in the power of love, and hope that the uninhibited and continuous flow of love, will one day drown the rampant cacophony of hatred and lilacs will again bloom.

Poets like Pablo Neruda will not expect us to ask, and where are the lilacs? Bandits will not come through the skies to kill children and the blood of the children will not run through the streets. Gunfire and blood followed the Spanish civil war when the smiles, the brilliant hues, the vibrant life, the flowers, the cavorting children all vanished, and Neruda was left with the bruised notes of this heart- wrenching poem, from which I have taken the title of my book.

How poignantly Neruda writes,

“And one morning all that was burning,

one morning the bonfires

leapt out of the earth

devouring human beings.”

Why should humans fall over humans with cannibalistic glee? Why indeed!

Lopa Banerjee: You write about the Kalashnikov in your characteristic heart-wrenching expressions in the poem ‘Such A Cruel Thing This Kalashnikov’: “Ah, It is small in size/But severs all earthly ties/Plays dangerous games/And is obsessed with changing names.” Would you say that Where Are The Lilacs is meant to be an eye-opener for the perpetrators of war and turmoil, as much as it is for the young children born into this world, who, you hope and wish, “do not have to ask Santa for bullet proof jackets, a world where childhood is a synonym for happiness”? What would you have to say about the book as a legacy for them?

Santosh Bakaya: Well, I have always maintained that hatred is corrosive, hatred cannot beget love, and only love can beget love. The war – mongers have always scoffed at the peace –lovers, contemptuously calling them peaceniks, and heaping venom at them.

It is not for me to say whether this book is a legacy for the children, I can only say that I have poured my anguish and my despair in this book, and the hope that someday, humanity will realize the colossal folly of being inhuman, and our children can move around without any fear.

War in any form is bad, how can the bludgeoning on innocence, strangulating of juvenile dreams be justified?

Lopa Banerjee: I remember you stating in an interview regarding another book of yours, which Reena Prasad, poet and editor too, mentions in the foreword to the collection: “I did not have to make any conscious effort, these slivers of memory just erupted from the subterranean depths, fitting into the narrative smoothly.” How true are these words about this particular collection of poems? I guess at least some of the poems here have evoked the sense of a vibrant nostalgia of idyllic times gone by as you have depicted a cramped apartment, the hushed innocent sleep of an infant, the anguish of an old woman who had ‘borne many a slingshot’. What part does your memory play here, vis-à-vis the depiction of the metaphorical truth that is a poet’s biggest tool?

Santosh Bakaya: Yes, the nostalgia is always there. Always.

I have had a wonderful childhood, loving parents, who showered us with love, without pampering us. It is the untrammeled flow, the frothy effervescence of love that can keep the world going. Hatred will destroy this world, making us go back to the Hobbesian state of nature, which was ‘nasty, brutish and short’.

Lopa Banerjee: The phenomenal poet Robert Frost had famously said about poetry: “A poem begins as a lump in the throat, a sense of wrong, a homesickness, a lovesickness.” You have authored two poetry collections, ‘The Ballad of Bapu’ and ‘Where Are The Lilacs.’ Many of your poems have found home in national and international anthologies, journals and e-zines, and also, you have been a featured poet in Pentasi B World Friendship Poetry. Besides, you have received the International Reuel Prize for literature in 2014. As a renowned advocate of poetry, what is your take on these words of Frost?

Santosh Bakaya: Yes, I do agree with Robert Frost, as many of my poems have begun as a lump in my throat, followed by a crushing sense of rampant injustice. The bludgeoning of innocence, the sufferings of refugee children, and devastated mothers, have always brought a lump to my throat.

Nostalgia has always been a part of my poems, nostalgia for the times when it was joy to be alive, nostalgia for the times when chasing kites and butterflies was a serious preoccupation demanding single-minded concentration, and plucking guavas from the neighbor’s garden was the happiest pursuit on earth.

Yes, homesickness has also been a recurrent theme in my poems. Home is definitely where the heart is, so at times, I feel as if I have left my heart behind in the flowerbeds, the rockeries, the terrace, the garden of my childhood, and I keep revisiting them through my poems.

Although I hail from Kashmir, I was not born there, yet, I keep going back to scrape my roots there, and am happy to find myself still thriving there, under the overgrowth.

Yes, I yearn for a profusion of love in this world so that all the hatred, animosity, ill- will and rancor is buried deep under this deluge. Yes, I am love-sick, forever craving for love to replace hatred.

Let me tell you something, I had gone to Accra, Ghana, West Africa in May 2016 as one of the delegates to be part of an international poetry event, co – hosted by Pentasi B and the Ghana Government and to receive the Universal Inspirational Poet Award. One day, while on a visit to Jamestown fishing Village, a small, poor child, maybe five or six years of age, erupted from somewhere, and hugging me tightly said, “I love you!”

It was indeed a precious moment for me, bringing home to me the power of love. That poor orphan had nothing to give me, just his eloquent bony arms which spoke the language of unadulterated love.

It is not too difficult to give love, and I have a fervent hope that the white dove flying diffidently in the petrified skies, will one day gain a sure-footedness, and strike a chord in hearts sequestered in hate, and those hate – clogged hearts too will burst into peace songs.

‘Where are the Lilacs?’ is available in Amazon India, Amazon.com, Flipkart and in the website of Authorspress India.

Amazon.in:

Amazon.com:

Lopa Banerjee is an author, poet, editor and translator based in Dallas, Texas. She has co-edited two books with Dr. Santosh Bakaya, ‘Darkness There But Something More: An Anthology of Ghost Stories’ and ‘Cloudburst: The Womanly Deluge’, a poetry anthology with 28 contemporary women poets of the Indian origin.