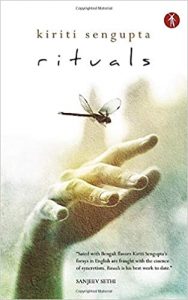

Rituals by Kiriti Sengupta

Reviewed by Shikhandin

In his introduction to Kiriti Sengupta’s Rituals, US based poet and editor Dustin Pickering writes, “Ritual, properly understood, signifies gratitude, and is rooted in the habitual nature of the human organism.” Sengupta’s poems dwell on this aspect of ritual, what is ritualised, and occasionally ritualist. His poems are both personal meditations and commentary, with a mildly wry sense of humour, appearing and disappearing like an elusive spice. The poems often play hide and seek with their metaphors and images, as if the poetic persona’s purpose is to throw the reader off the track, only to bring them back with an enticing hook. This happens in poem after poem. Why and how does Sengupta do it?

Visualise the poet leaning against a barred window, looking at the world outside. His posture may be idyllic, but his mind is not. As he watches what is beyond, he makes observations, he mulls and muses. He forms opinions and further reflects on them. Rituals is the product of a series of apparent inactions, wherein the poet remains physically still, within the world although not entirely a part of it. It poses a paradox of sorts. Many of the poems act as riddles, even as they are full of sorrow, angst, love, gratitude—as if sprayed in a fine mist. On occasion, they are huddled like evening shadows—four emotions in a single poem. Like “Observance” for instance, a poem in four parts, which Sengupta concludes by admitting, “I witness this from a distance.” And then poses the question, “Does proximity help in faithful depiction?”

Rituals is not only about poetry built with words, its narrative draws on illustrations as well. The meditative quality of the book is deepened by the black and white-washed images that accompany poems. The illustrations by Partha Pratim Das are akin to Chinese brush painting and have an ethereal quality. They capture the barest essence of the poems, creating their own visual story. The poems and illustrations together create a jugalbandi of thought and image. Physically, the book delights with its elegance. Reading it is a mindful experience.

The book opens up with the pair of poems – “Comeback” and “Resurrection.” The prosaic poems create a near mirror effect, reflecting images back and forth. In “Comeback,” the poetic persona returns like a prodigal. The setting is a room, which though covered with “thick silt,” is just as it was a year ago! One senses bereavement here, though not necessarily pertaining to death. Nostalgia, like “the filth radiates intimate odor” and “tired eyes uncover the kohl of night,” while the poetic persona’s “glasses spot tears.” In “Resurrection,” the setting is once again a room. Is it the same room? Sengupta offers clues, but they could lead the unwary reader elsewhere. Perhaps in “Resurrection,” the persona is not returning to the room, but is seeing it as a fragment of memory, which the illustration on the facing page amply corroborates. He is watching a slice of another life when the “tiny particles scattered in the air absorb the sunlight; …Sleep is now conscious like the attraction between mother and her new-born…the room is ready for hard work.” The imagery is wilfully connected with seams, like parts of a broken mirror reflecting different things that still belong. The analogy of sleep as a baby in a mother’s arms is evocative; it is implicit at the start of the poem but progressive clear.

“On the Richter Scale” is one of the longer poems, also prosaic with three parts. Its chimeric amalgamation of images creates an unsettling effect on the reader, like experiencing an earthquake in one’s mind. The disjointed metaphors ultimately turn earthquake itself into a metaphor. Or at least the measurement of it. The following lines connect each of the three parts together, like a riddle:

i “4 on the Richter Scale sits comfortably on the human body.”

ii “The scale marks 5. Does vapor perspire?”

iii “Desolation stands still. The Richter scale fails to respond.”

Sengupta’s habit of throwing of riddles at the reader and quizzing them continues in “Appraisal,” a poem in two parts, in which he asks, “Do you consider Nature baffling?”

In poem after poem, he continues this technique, almost loth to let go. In “Where God is a Woman,” he slashes through society’s curtain of hypocrisy. Here I must add for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the Bengali festival of Durga Puja, that the Devi’s idol is made with clay, a small portion of which comes from a brothel.

There are small poems that spring up like April blossoms, bright with imagery, startling with the luminescence of fireflies. In “Accommodation,” Sengupta muses on the irony of life from a fern’s point of view. “Kalpavriksh” provides a tiny dose of spirituality. “Gravity,” creates a metaphor for turbulence. In “Screenplay,” the title plays an important role in accentuating the irony in the poem.

Humour too wends its way into the book. In “Timings,” for example, Sengupta does a tongue-in-cheek exploration of friendship as also in the pithy, three-lined “Dentures.” At times, Sengupta is too concerned with opening an issue, but disinterested in providing solutions. His intention is to rile and provoke because truth is both universal and particular as well as subjective. Sengupta too being entitled to his own subjective truths.

The thoughts, moods and ideas expressed in the book are succinctly represented in Sengupta’s eight-liner, “Tradition.” The poem works as a distilled core of the entire collection, Sengupta might have as well ended the book with it:

“I have no choice but to listen

to the same words again and again.

Neither am I aware of consequences.

It is not cerebral but sensory.

Customs are like meditation –

worthy of unhurried contemplation.

Practice adds to their maturity,

I know servitude is congenital.”

Closing the book, I felt these words sink in, not like a sediment at the bottom of the glass, or a stone at the riverbed, but like cotton wool soaked to saturation, which must now float downwards. In the process I find myself re-experiencing Sengupta’s Rituals, much like the mirror in “On the Richter Scale,” which “bathes in glassy water to reflect light.”

![]()

Shikhandin is an Indian writer who writes for both adults and children. Her short story collection “Immoderate Men” was published by Speaking Tiger. Her illustrated book for children “Vibhuti Cat” was published by Duckbill Books. Shikhandin’s accolades include, winner 2017 Children First Contest curated by Duckbill in association with Parag an initiative of Tata Trust, winner Brilliant Flash Fiction Contest 2019 (USA), runner up Half and One Short Story Competition (India), Shortlist Erbacce Poetry Prize (UK), first runner up The DNA-OOP Short Story Contest 2016 (India), 2nd Prize India Currents Katha Short Story Contest 2016 (USA), winner Anam Cara Short Fiction Competition 2012 (Ireland), long list Bridport Poetry Prize 2006 (UK), finalist Aesthetica Poetry Contest 2010 (UK), Pushcart nominee by Cha: An Asian Literary Journal 2011 (Hong Kong). Shikhandin’s work has been published worldwide. Notably in HuffPost India, Scroll.in, Jaggery (USA), Asia Literary Review (Hong Kong), Eclectica (USA), Per Contra (USA), Markings (Scotland), Himal Magazine (Kathmandu), Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine (UK), The Nth Position (UK), Mascara Literary Review (Australia), Cha: An Asian Literary Journal (Hong Kong), Stony Thursday (Ireland), The Little Magazine (India), Out of Print (India), Sybil’s Garage (USA), Pushing Out the Boat (Scotland), South: A Journal of Poetry (UK), Off the Coast (USA), Etchings (Australia), Silver Blade (USA), Going Down Swinging (Australia), Scoundrel Time (USA), Reckoning (USA).