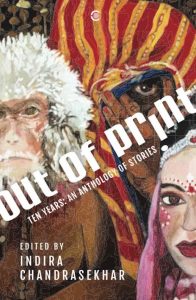

Out of Print, edited by Indira Chandrashekhar

Reviewed by Sushumna Kannan

Out of Print: Ten Years, An Anthology of Stories is easily the best platform for publishing short stories in India today. It is dedicated to short stories alone; is online and easy to access. This book is a 10th anniversary publication that brings together stories already published in five sections, titled ‘Making the Myth My Own,’ which presents takes on myths, ‘Angle of Incidence: Is My Vision of Myself an Illusion?’ which explores selfhood, ‘Oracles and Beating Hearts’ –a bunch of love stories, ‘Living Together: Crafting Place from Layers of Memory’ exploring gender and space and a final section titled ‘Reality Imagine,’ of twelve translated works. Each section has a comment by the curatorial editors that makes apparent the logic underlying the selection of stories. As the introduction lays it out clearly, the book presents trans-generational diversity, is multilingual, contains pre-pandemic writing and is not a collection of the best of Out of Print’s stories over the decade.

The stories are selected as a response to world currents aiming to capture India in a wide-ranging timeline reflecting issues dominating our collective psyche; “a documentation of ten years of writing connected to the Indian subcontinent.” This documentation, of course, is left-liberal in perspective, with identity politics being the focus of several stories. For instance, queer experiences, caste issues, Kashmir and the Northeast—are topics explored in the stories. The preoccupation with identity politics, as is well-known, is a double-edged sword, notorious for stifling true creativity. In this book, it works well at times and fails at others.

My major grouse with the book is that the mythology section is sorely lacking for ignoring stories that have a positive association with mythology, thus ignoring the new wave of literary writing and speculative fiction that has reclaimed mythology without necessarily challenging it. Here is where I feel the book fails to deliver on its claim of reflecting issues dominating our collective psyche. This, of course, has to do with the ideologies that drive the curation of the magazine itself, perhaps something to think through or perhaps the level of claim made on behalf of the book can be reduced instead. Most stories in the section on mythology emerge from a perspective of critique and relating it to the present. Shashi Deshpande’s “The Three Princesses of Kashi,” which is the best in the section, still falls short of a proper treatment of myths. Her questioning of Bhishma’s abductions of the three sisters, Amba, Ambika and Ambalika, (allowed as an exception for kshatriyas, and generally an unrecommended form of marriage in the dharmashastras) is something the Mahabharata keeps open just as it allows Draupadi to ask the questions that she did of her husband, Yudhisthira. Deshpande’s critique of the practice of niyoga is similarly already potentially present in the Mahabharata given how the dharmashastras do not recommend it for later times, having likely imbibed the Mahabharata’s perspective of women’s experience of the practice. Deshpande’s critique emerges from a fundamental misunderstanding of what women’s duties were in the epic world. It offers a limited relation to the past anchored strictly in the present. Yet, Deshpande’s characters also exhibit layers that keep them partly authentic to the ones found in the epic, albeit with added speculative thoughts and actions. Also, mythical traditions would themselves admit that what “women bear” is equal to the performance of penances. It is therefore that their curses are powerful as revealed by Krishna regarding Gandhari. The rest of the stories in this section relate to mythology in broad strokes, not necessarily engaging them directly or deeply. “The Dolphin King” by Kuzhali Manickavel is funny and Senthil’s character is narrated in a relatable way. The mythology in this story is relatively less, and not particularly distortive. “Seven Little Rooms” by Mridula Garg is an engaging read, almost ethnographic in its tone. Annam Manthiram’s “The Reincarnation of Chamunda” is a gendered response to the pressure on marriage placed on women. “The Moon Mountain” by Shaheen Akhtar, clearly a story about the environment and the violence of development is about making the myth of home one’s own. “The Year of the Kurinji” by Vidya Ravi references Draupadi but suffers from the same drawbacks as Deshpande’s story.

The second section, ‘Angle of Incidence: Is My Vision of Myself an Illusion?’ begins quite aptly with U. R. Ananthamurthy’s “Apoorva,” which depicts a failed marriage. Next, Anjum Hasan’s “The Big Picture” offers warm portrayals of an aged artist ending in a destabilizing realistic moment that sheds light on the irrationality cohabiting human selfhood. Vasudhendra’s well-narrated “Bedbug” tracks a queer person’s tragic end in a village household; it has a rare authenticity to it. Zui Kumar-Reddy’s story explores the starkness of child sexual abuse within the home in a bold manner, exploring the vagueness around it, followed by Mohit Parekh’s “Recess,” which explores several sides of the teen experience of pressures regarding masculinity. Chandrahas Choudhury’s “Dnyaneshwar Kulkarni Changes His Name” explores the awkwardness of a quintessential urban life in India in an endearing way; it is a totally enjoyable story with great humor and timing.

The next section “Oracles and Beating Hearts” begins with Jayant Kaikini’s story of love in a late bloomer and his sudden but stubborn hopefulness. It speaks of the powerful hold of love on humans in the most unforeseen of ways and times. “The Other One” by Hasanthika Sirisena took me by surprise, for although it had characters placed in the diaspora, its attention to identity issues was minimal; it normalized the characters’ presence in such locales, exploring life and relationships as they panned out, instead. “Sujata” by Annie Zaidi stayed the longest in my mind. A story about domestic violence, it is hard-hitting but so well-written that I reveled in its narrative and the single minor twist which sealed it’s end perfectly. The story demonstrates so well that it’s not always twisty plots that maketh good stories; deft meaningful narratives suffice too. Zaidi doesn’t expend any breath on the violent man, seeking to analyze his character or providing a backstory for him, which is so apt, beautiful and satisfying. “Black Dog” by Shruti Swamy explores friendship and young love in a dynamic and hearty manner. The sentimentalism and innocence of intense young adult love is truly moving in this story; it’s nuances are very well-brought out.

Tanuj Solanki’s “The Issue,” modeled after Alan Rossi’s “The Problem at Hand” presents a dense and thick narrative of a couple in disagreement, constantly attempting dialogue but going around in circles, fearful of leaving a familiar past behind and anxious about entering an unfamiliar future. Peppered by the realistic presence of a lizard in the house that governs the beginning and end of the story, the story captures a marriage at its core. Although addressing a fairly modern issue, that of women’s equality, it could really be about any marriage—modern or traditional, love or arranged. One wished for more dialogue to ease up the thick description and reportage in the story, however! “The Itinerary of Grief” by Chika Unigwe explores yet another identity category, that of a traveler to India, which is filtered through the lens of personal grief. So that we have gems such as this: “…but he asked if I had a husband. Back home, I would have taken it as a sly but cheesy pickup line, but I had been in India for over a week and knew that it was conversation and nothing else.”

The subsequent section, ‘Living Together: Crafting Place from Layers of Memory’ has “Bittersweet” by Gangadhar Gadgil, which portrays a stifling family system followed by “Mischief in Neta Nagar” by Altaf Tyrewala, which averts taking politically correct stances in a story on the Muslim identity and co-inhabiting social spaces and the resultant religious conflict.

“The Currency has Changed” by Krishna Sobti is a partition story written in 1948 but eerily resembles certain take downs of the demonetization of 2016. “The Retired Ones,” by P. Lankesh brings the retired and aged tous, hanging together in Lalbagh, a park in Bangalore and captures modernity as well as U. R. Ananathamurthy’s story, manifesting as a gap between what one thinks to oneself and what one says to others. “Jenna” by Anita Roy explores a women’s prison and completely deflects the question of why a mother would hurt her child, through the vivid description of a prison cell.

The final section ‘Reality Imagine’ has “Do It by the Numbers” by Shabnam Nadiya, on intimate partner violence. “Honour” by Ajay Navaria takes caste discrimination head on, especially the flip side of village panchayats. The three stories on caste in the book side solely on the ethnographic understanding of caste rather than aiming to bridge it with a theoretical understanding of caste—a rift that has long driven both scholarly and fictional forays into the topic. And, even within the ethnographic understanding of caste, the book’s stories lean towards descriptions that highlight inequality rather than the ones that muddle up ideas of boundedness and rigidities via syncretism. Next is “The Chameleon’s Game” by Azra Abbas, a Pakistani writer. “The Graveyard” by Ali Akbar Natiq, another Pakistani writer, depicts the ills of classist cultures within the Muslim community. “The Bar” by Paul Zacharia is another plotless exploration of urban life. Mustansar Hussain Tarar’s story is next. He is also a Pakistani writer. It is not apparent why Pakistani writers are included in a book that tracks India. Dalpat Chauhan’s “Home” also explores caste in a village.

In many stories, realism is used to cut through the fog of social conditioning, as it were. But Marx’s own insights show that a wholescale removal of humans from society for the purpose of analysis is impossible. Hence, the intellectual and creative choices of these stories lie further back in their foundational blocks, rooted as these blocks are, in moves against social conditioning and often against tradition. There is a story about partition, but colonization’s effects are conspicuous by absence. Colonialism’s lasting effects persist in India today and not acknowledging that leaves a void. This is especially important when speaking about caste since several semi-indigenous institutions of caste at the village level are somewhat frozen now, while even a 100 years ago, kings would revise caste rules and lift the social ranking of castes from time to time based on their charity work or other contributions to society, rewarding them from time to time.

At a time when literary festivals, educational institutions, publication houses and the internet have opened up to engage with a wide variety of socio-political and cultural views, why should online platforms for creativity such as Out of Print restrict themselves to the left-liberal camp? Creativity can flow any which way! The book is not entirely a nonpartisan endeavor, inclusive of multiple positions and histories in documenting Indian writing, but sides with one kind of politics. If any of the emerging new speculative fiction on Indian mythology had been included to provide alternative perspectives on the same issues, this book could have easily been a richer attempt in educating India’s next generation of writers.

![]()

Senior Reviews Editor Sushumna Kannan has a PhD in Cultural Studies from Centre for the Study of Culture and Society, Bangalore, India. Her research on the South Asian devotional traditions and feminist epistemology focused on the medieval saint, Akka Mahadevi and her vachanas. She received the BOURSE MIRA, French research fellowship in 2006 and 2007 and the Sir Ratan Tata fellowship for PhD Coursework and Writing in 2003 and 2007. She has published her research on Bhakti, dharmashastras, ethics

visit: www.sushumnakannan.