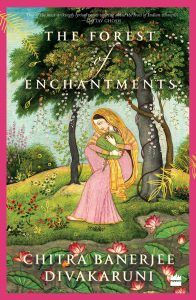

Forest of Enchantments by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Reviewed by Jyothsna Hegde

By Sita, of Sita, and for the Sitas of the world, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Forest of Enchantments amplifies the essence of the revered epitome of sacrifice and virtue in mythology, through the lens of Sita, zooming into not just her divine, but every womanly facet, humanizing her journey and highlighting her strengths.

Synonymous with fertility and purity, the traditional image of Sita etched in our minds is as the paragon of filial, spousal, and maternal merits, the ideal woman, a symbol of nobility. Divakaruni’s Sita, is all of that and something more. This Sita is every bit human as you and me, plunging into the abyss of despair, anger, frustration and rising to the pinnacle of elation, serenity and satisfaction. It’s not that ‘Sitayana’ has not been attempted before, but Divakaruni’s Forest…lets you in on deeper, darker and even, enchanted secrets.

The Forest… stays true to the original script by Valmiki and is inspired by Kamban’s Ramayanas and the 15th century Bengali Krittibasi Ramayan, as the author mentions in her introductory note. So then, what sets this Sita apart? In this Sita, the narrator, has a distinct voice and is not afraid to use it. And, here Sita’s character is layered with a myriad of dimensions all of which emerge at different stages of the narrative. This Sita empathizes and pays tribute to all the women of Ramayana, even those outcast and undermined. She reasons and demands, even as the young princess of Mithila and asks: “Why can’t customs change? Especially ones that don’t make sense?” when her mother Sunaina tells her that the kingdom of Mithila can be ruled only by a man.

Sita is well-versed in martial arts and is a gifted healer whose magical powers cure the ill with herbs from nature. And so, she loves to preserve the green around her. Her fierce passion for the environment unravels multiple times, including when she requests Ram to ask his soldiers to chop the least number of trees in the jungle to make way from Mithila to Ayodhya. She is empowered and an environmentalist!

Advised by her mother to “endure”, Sita does so, all the way – when she relinquishes comforts of the palace to spend 14 years in the forest with her husband, when she waits for Ram in the firm belief that he will win her back from the clutches of Ravan, when she enters the fire to prove her purity, when she raises her twin boys in the forest after being banished by Ram and eventually when she makes the crucial choice to preserve her solemnity.

“For the sake of my daughters in the centuries to come, I must now stand up against this unjust action you are asking of me,” declares Sita in the final chapter, asserting her right to choose between right and wrong, when asked to prove her fidelity for a second time in order to be accepted as the queen of Ayodhya. No shrinking violet, this Sita is empowered in the truest sense, willfully giving up her life instead of bearing the brunt of injustice inflicted upon her, because, as she puts it, “this is one of those times when a woman must stand up and say, No more!”

Even as this Sita gracefully embraces womanhood in its entirety, allowing her beauty to manifest through her inner strength, Divakaruni never undermines the underlying melancholy that engulfs Sita all along her tumultuous odyssey. As human as her portrayal is, Divakaruni is careful to make plenty of room for mysticism, adding color to her canvas. So Sita often has visions of her future, not essentially in the way it would happen, but glimpses that guide her to where she might be headed, and often, it leads her down some dark paths.

It is not just the story of Sita that occupies center stage. The other women of Ramayana claim their due credit too, because as they voice out in the novel, they, “have been pushed into corners, trivialized, misunderstood, blamed, forgotten – or maligned and used as cautionary tales.” So Sita sees her mother Sunaina as a wise queen who advises her husband, king Janaka about matters of the state only within the confines of her quarters but allows him to bask in the glory of its reaping. Urmila, Sita’s sister and Laxmana’s wife is the ideal sister and wife, without a strain of jealousy, ever giving, always supportive. She is also someone whose sacrifice is overlooked. While Ram allows for Sita to follow him to the forest, Urmila, who also wanted to accompany them is denied the chance and Sita acknowledges her suffering. “Forgive me, Sister,” says Sita “silently, you who are the unsung heroine of this tale, the one who has the tougher role: to wait and to worry.” Sita also relates to Ravana’s sister, Surpanakha’s pain, of being wronged by two men, even though her complaint to Ravana about Ram and Laxman disfiguring her, triggers his anger into kidnapping Sita. “I could see the men wouldn’t change their minds,” says Sita having watched her husband and brother-in-law toss Surpanakha between them. “Their belief in the superiority of their own ways was too deeply ingrained for them.” Ravana’s wife Mandodari, is a queen in the true sense, abiding by her husband but allowing for her dignity to shine, nevertheless. In Kaikeyi, Ram’s stepmother who banishes him to fourteen years of forest and strips him of his kingship, Sita sees an accomplished charioteer and warrior who simply wanted her son to rise above the rest.

But then the most precious treasure in this enchanted forest in the love that Ram and Sita share, that blossoms with time, only to be tested over and over again. Divakaruni weaves this strand with tender love and care. So even in her final act of defiance, this Sita forgives Ram because she has discovered the other face of love, compassion. “It isn’t doled out, drop by drop,” says Sita. “It doesn’t measure who is worthy and who isn’t. It is like the ocean. Unfathomable. Astonishing. Measureless.”

Self-sufficient and self-aware, Divakaruni’s Sita in her roles as a daughter, sister, wife, daughter-in-law, and mother is dutiful as she is defiant. She will compromise her luxuries but not her self-respect. This bold and beautiful Sita may very well be the feminist of the Treta Yuga, and Kali Yuga, even!

Someday, when my now 6 year old daughter reads the Ramayana, I would like her to explore this enchanted forest to discover the courage of Sita who conformed to all social boundaries and yet managed to hold her own and hail her dignity, even at the price of giving up much: being a queen, a mother and ultimately, her very life.

The succulent sudha (nector) of this Sitayana, laced with sour traces of sorrow lingers long after consumption of its last page. And then some.

![]()

Jyothsna Hegde is City News Editor at NRI Pulse newspaper and an independent software consultant. She holds a master’s degree in Computer Science and has served as faculty at Towson State University. She is drawn to literature of all kinds and finds immense pleasure in sharing the triumphs and tribulations of the indomitable human spirit through her writing. She has been part of the organizing committee of Kannada literature featuring top pandits in the field and also enjoyed being part of the 45th Anniversary Souvenir edition, Chiguru, of Nrupathunga Kannada Koota. She believes that literature is the only form of expression that has been and will continue to be part and parcel of human life through the ages and beyond.