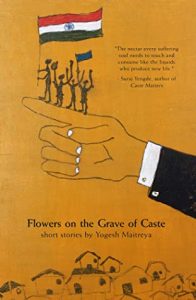

Flowers on the Grave of Caste by Yogesh Maitreya

Reviewed by Kiran Bhat

What does it mean to represent Dalit-hood, not as a condition, but as an aesthetic? In Yogesh Maitreya’s life, writings, and work, he has taken on this very monumental question. His project is to change the way that we as Indian readers perceive, treat, and interact with Dalit-ness on the page. This is not to say that Maitreya is creating narratives from a Dalit perspective that can be boxed into this or that version of identity politics. Oh, no. Maitreya is too specific for that; he wants to remind us very much of the random killings of Dalits by Brahmins in villages, the big city manual labourers lost to the floodings inside sewers, and artists whose dreams are crushed by a life of passive aggressive comments and constant rejections. What makes Maitreya’s work stand apart is the way his sentences hunch forth, as well as his mastery of symbol and structure. For Maitreya, the short story is just as much of an art form as it is a vehicle for social change. As a result, Flowers on the Grave of Caste is an important piece of literature not just for those who are keen to see Dalit writers fleshed out, humanised, and moved to the centre of literary discourse, but for those who are keen to see a young visionary of the short story form embark on a career of much promise and potential.

I will start with the most fulfilling story of the collection, “Life is Beautiful.” We begin the story in the perspective of Sadashivrao Kulkarni, a humble Marathi teacher from Vidarbha who is lynched for falling in love with a Brahmin woman. Their son Vishnu becomes a priest of great fame and success, with devotees coming from all corners of India to receive his blessings. He is visited by Nagraj, a sewer worker who aspires to see his son’s blossoming talents for painting achieved, to the point that he will work any job, or take on any task. What makes “Life is Beautiful” work is Maitreya’s ability to enter into three very different voices with authenticity and empathy, and to blur them into an omniscient streaming third person narrative. It is certainly not effortless. For example, Nagraj is introduced with ‘Vishnu [receiving[ offerings (cash and kind) ….from the temple,’ and then, looking outward, ‘he [becomes] worried and irritated that he [has] to see Nagraj, a Safai Kamgar, every day.’

That is it. Vishnu’s disgust at observing a lower caste person is the space at which these two narratives link, and then Vishnu’s voice disappears, the story becomes entirely Nagraj’s. Maitreya’s decision to have these two voices change so abruptly has a jarring affect, and I was even wondering if these lines were meant to be a transition, or the introduction of a side character for many paragraphs after. On a second read, I realised how intentional Maitreya’s slight at his own character was. After all, how often do people who are priests, manual labourers, and humble villagers meet at the same level in modern Indian life? The stiltedness of the transition works to remind us that most lower-caste people in literature, culture, and even general society are introduced not through their talent or prowess, but from a perspective of disgust and annoyance.

Another story of note is “The Sense of a Beginning.” Aspiring writer Kabir centers the narrative of a university student who is caught between the world of academia and his life as a Dalit. Kabir briefly dates Saira, but their relationship falls apart because of their differences in backgrounds. Kabir’s poor English and inability to relate to the university world further, his ability to connect with his professors and classmates. Unable to move upward, Kabir loses himself to alcohol and drugs. The story ends on a hopeless, albeit realistic note: “My father and mother certainly had dreams. But their dreams have neither become the story nor the history. What is the story of their dreams?”

We will never know, because just like the story’s ending, it is implied that Kabir’s dreams too are meant to end much like the story itself, abruptly, suddenly, and unfulfilled.

And then there is “Flowers On The Grave of Caste,” the most brilliant piece in the collection by far. The narrative takes the shape of an interview between Nagya and a two-hundred year old gravedigger. In the most philosophically profound and expansive story in the collection, Maitreya muses on the construction of history, the passing of time, and those who are lost to our collective consciousness as a result of this intersection. “Dead people do not have any religion. It is the people who are alive that see dead people as part of a religion.”

My soft copy of Flowers On The Grave of Caste is littered with highlights. That is how fresh the use of language in the book is. There are just too many insights beaming on the page, or casually shimmering a sentence to light. For example, the story “Re-evolution” begins with the narrator observing “outside [a] bus window, under the scorching sun in the month of May, … eagles in the sky, flying in circles, screaming, as if celebrating life.” As he glimpses on this horrific hunt, the narrator recalls the wise words of a fellow villager: “When any evil spirit on earth dies, eagles fly in circles and scream. Their screams imply that justice has been carried out by nature.”

The brutality of the scene coupled with the sparseness of the language set the scene for a narrator whose life, much like the claws of vultures against carrion, is torn apart viciously by the unfairness of caste discrimination. Similarly, the narrator Kabir in “The Sense of A Beginning” reflects on how different he is from the world of academic Mumbai. “People here looked different; they smelled different. I wanted to smell like them, I wanted to fit in their world, secretly. Yet I couldn’t.”

Because fundamental differences are often impossible to reconcile. But Maitreya’s characters do not always relent, or give into the pressures of the society they are forced to be born in.

As a father reminds his child in “Life is beautiful,” we must recall the following: “Remember, generations our people have been destroyed carrying the shit and burden of this society. You should aspire for a life of truth and beauty.”

Indeed, Maitreya writes with nothing but truth and beauty brimming over his pen. A storyteller with the firm social convictions of a Gorky or Premchand, but with the ability to dissect and disseminate insights into the human condition much like Chekhov or Manto, Flowers on The Grave of Caste is the debut of an author who has too much to say, is already making his mark on the literary world, and will write many great works of genius in the years to come.

![]()

Kiran Bhat is a global citizen formed in a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia, to parents from Southern Karnataka, in India. He has currently traveled to over 130 countries, lived in 18 different places, and speaks 12 languages. He is primarily known as the author of we of the forsaken world... (Iguana Books, 2020), but he has authored books in four foreign languages, and has had his writing published in The Kenyon Review, The Brooklyn Rail, The Colorado Review, Eclectica, 3AM Magazine, The Radical Art Review, The Chakkar, Mascara Literary Review, and several other places. His list of homes is vast, but his heart and spirit always remains in Mumbai, somehow. He currently lives in Melbourne. You can find him at Kiran’s Weltgeist.