The Dignity of an Unheralded Artist on the Streets of Bangalore

Richard Rose

For two consecutive days when returning to my accommodation after an early morning walk I cursed my ill-fortune at having missed an opportunity. Determined to make amends, on the third morning I started my promenade of the streets of Jayanagar in Bangalore forty minutes earlier than usual, and stepped out with greater purpose than before. 5.30 am is a good time to explore the lanes of the city on foot. It is only at this point in the day the pedestrian is afforded a rare opportunity to walk in relative safety, before the chaos that constitutes the traffic of this vast metropolis has bludgeoned every walker with the least regard for personal safety into submission. It was therefore with some confidence that I made my way through the labyrinth of lanes which spread like tentacles from the main thoroughfare through the urban sprawl of Jayanagar.

Usually on these dawn excursions my wanderings are fairly aimless, following no regular pattern and having the sole objective of exploring the area in order to gain my bearings and take some exercise before the commencement of a day’s work. But on this particular occasion I was more focused and set out on a quest; hopeful of discovering an artist at work and with any luck to witness creation in progress, rather than simply viewing the results of the creator’s labours. Whilst I had every confidence of locating the venue where today’s masterpiece was likely to be found, I was less assured that my timing would enable me to view the artist whilst engaged in the act of producing her work of art. But, as is the case with many journeys, I set out full of hope if not expectation.

Rangoli patterns comprising a series of flowing whirls and geometric motifs are a common enough sight on the pavements and thresholds to be found in the backstreets of Bangalore, as they are in other parts of India. On many occasions I had stopped to admire the intricate swirls and interweaving patterns produced by the women who fashion these elaborate designs. There had been instances when I had caught a glimpse of an artist, bent double from the waist putting the final touches to her work, but as yet I had failed to observe the whole process, from the first outlines made precisely with the delicate placing of the red ochre sindoor stained flour, to the completed geometric shapes flowing from the delicately placed utswdhermita, which signify a conclusion to the process. Wishing to address this omission in my experience of Rangoli production and knowing that these skilful women work quickly, I made my way to the narrow lane where I had on the previous two mornings found elaborate examples of these intricate but ephemeral works of art. Timing is critical to those who wish to find these pavement Rangoli designs, which within a few hours of their production are inevitably be swept from the streets by the passing of many feet as local pedestrians go about their business. Hopeful that I would arrive before the artist began her labours I took up my position and waited.

There are many myths and legends surrounding the production of Rangoli, some associated with the deity Mahalakshmi, of whom it is said that she will bring good fortune to the house outside which a woman makes a pattern whilst chanting sacred mantras. I have noticed that during festivals such as Dusshera, celebrated at the end of Navatri each year in Bangalore, there seems to be a small increase in the number of Rangoli patterns to be found on the streets. As is fitting for a festival closely associated with a celebration of the bounties of harvest, during this festival these incorporate natural materials often incorporate flowers, seed pods and leaves within the design. During this period it is possible to make a circuit of the district and to see several variations in design, colour and texture amongst these traditional patterns.

But today I was in pursuit of observing a single artist at work. One whose finished design I had seen on both previous mornings, and whose intricate patterns had held my attention and fascinated me by their complexity. For this reason I arrived early at the venue and took up position across the narrow road from the house from which I hoped the lady would emerge. After ten minutes I began to feel concerned that my mission was in vain, there was no sign of an artist and I began to curse my own stupidity for having missed an opportunity to see an artist in action, which would clearly have presented itself had I arrived earlier during my previous visits to this site. But just as pessimism began to gain the upper hand a lady emerged through a gateway carrying a large metal bowl, the contents of which I could not at first discern. As she took up her position on the path outside of her house I indicated to her that I wished to observe her at work and checked that she was comfortable with my presence. Her English was marginally better than my Kannada and I was therefore grateful when she smiled and indicated that she was quite undisturbed by my interest in her morning ritual.

As I watched she began by creating an almost perfect circle of bright vermillion. This was done quickly filling her hands with powder from the large bowl which was delicately balanced on her hip and turning herself about, until every part of the circle was filled to present an even canvas upon which she could work. At this point she removed a smaller pot from within the large bowl and commenced to create an elaborate pattern using what looked to my uneducated eye, to be either sand or salt. The whiteness of this medium stood out boldly from the background red as she utilised her finger tips as a delicate channel through which to feed the powdery substance. From my vantage point some five metres away, I could see how with a simple flick of her wrist and rubbing together of her fingers she was able to vary the flow of the powder, occasionally doubling back along a line to add thickness or emphasise a shape.

Within five minutes the whole process was completed and standing upright the artist offered only the briefest of glances at her creation before gathering her bowls together and making to re-enter her house. I felt that I wanted to applaud, but was unsure whether this might be seen as disrespectful of an activity, which clearly had significance and a deeper meaning for the artist than I might be able to understand. In saying thank you, I was aware that this hardly seemed sufficient reward for the opportunity I had experienced to observe the creation of something so beautiful in its simplicity. Having heard my far from adequate thanks, the lady smiled and with a simple shake of her head, a gesture that has so many meanings here in South India, she turned and was gone.

In watching this artist at work a number of thoughts went through my mind. Firstly, I suspect that the woman I had seen create this beautiful and clearly to her, significant image, would not apply the nomenclature of artist to herself. I would imagine that the creation that she laid upon the pavement today was similar to many others that she has produced over a number of years, and that her skills had possibly been learned from her mother and may well have been passed down through many generations. Who might define the artist I wondered? In my eyes she was the creator of a fine, if ephemeral work of art and therefore deserving of being seen as an artist. Others, including the lady herself I imagine might be surprised that I refer to her in this way, though I believe that I am fully justified in asserting that what I witnessed this morning was true artistic endeavour from an individual with skills and understanding that the majority of us could not replicate. For this reason I will not be dissuaded from the terminology that I have applied.

The nature of her work was of course ephemeral. I have no doubt that a return to the gallery in which she created her Rangoli pattern a few hours later, would have found the image if not wholly erased, certainly smudged and distorted. Does this devalue the work which she so lovingly made upon the pavement? There are many instances of artists who have produced work knowing it to be ephemeral and temporary in nature. A few years ago my wife and I attended an exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park of work from the British artist Andy Goldsworthy. This included images and sculptures made from a range of natural materials including flower petals, stones, twigs and leaves, all cleverly arranged to provoke discussion from the viewers of this eclectic mixture, used to produce what were most certainly works of art. Other artists such as Richard Long, Leonie Barton and James Brunt have created images in the landscape using the resources that come immediately to hand, such as pebbles on a beach, or pine cones and leaves, which will be erased by an incoming tide or scattered on the wind. For many such artists the beauty is as much in the act of creation as it is in the finished work, but this does not lessen the aesthetic of their efforts.

In India there is a long tradition of artists creating work which sits comfortably in the environment for a time before eventually fading away. The lively images of the Madhubani paintings traditionally produced by the women of the Mithila region of Bihar, or the wall paintings of the Warli tribes in Maharashtra State were never originally intended to have the permanency that we tend to hope for in much western art. In recent years the introduction of methods and materials to assist artists from these communities to place their art on a commercial footing, has begun to change the ways in which these images are regarded. This has resulted in new opportunities for today’s Indian artists such as Ratna Raghia Dhusalda, Bhuri Baï and Balu Mashe who, whilst maintaining traditional tribal approaches have gained recognition from a much wider audience. In the past the influence of such work extended to some European artists such as Picasso, Brancusi and Matisse who recognised that what others saw as simplicity in tribal works was often far more complex and imbued with meaning, and possessed an ability to communicate in ways that were largely misunderstood.

Whilst I would never suggest that the lady who granted me an audience this morning, as she produced her beautiful Rangoli could be compared directly to Picasso, I am prepared to say that they walk along a similar continuum of artistic endeavour. Both Picasso and this unheralded lady artist, recognise the value of art as a means of communication and have developed a set of skills and knowledge, which enable them to command the attention and admiration of those who care to stop and stare. Only the narrowest of minds would deny that the act of creation should not be only the preserve of those who receive formal recognition for their work.

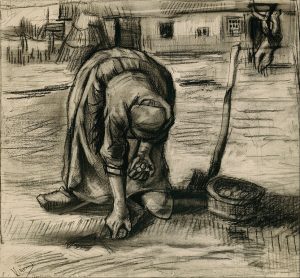

On one final note; whilst watching the lady artist at work this morning a further impression came to my mind. As I tracked her graceful movements around the pattern that she was so deftly creating on the ground. I noted that rather than getting close to the earth by flexing her knees, all of her work was performed by bending at the waist. This image remained with me throughout the day until I suddenly realised where I had seen it before. At the first opportunity I turned to a book which catalogued much of the work of Vincent Van Gogh and searched for the series of drawings that he produced whilst living in Nuenen between 1883 and 1885. Here in Van Gogh’s work I was able to refer to the collection of pictures, which honour the dignity of the peasants who lived in this Netherlands village. Many of the drawings depict women working in the fields, some of whom, just like today’s Bangalorian artist are bending from the waist to work close to the ground with their hands. An image of a woman planting potatoes and another simply described as “peasant woman bending down” from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo could easily have been a representation of the Bangalore street artist at work on a Rangoli design.

Here then is the true value of art. In observing what many would undoubtedly regard as a simple domestic task on the streets of Bangalore, I have had the pleasure of seeing an act of creation by a lady artist whose movements have led me on a journey to consider the nature of the created image. This has included a reflection upon the coming together of western and eastern influences and the relationship between labour and beauty. Now, who will dare to tell me that the lady who I was privileged to see at work this morning is not an artist whose work deserves to be celebrated alongside that of others who assume this title?

![]()

Richard Rose is a writer and university professor based in the UK. He has been working regularly in India for the past 20 years. His short fiction has appeared in international literary magazine, including Spadina Review, Indian Review and Muse India, and his non-fiction has been published in Coldnoon, Spark and the Bangalore Review for whom he writes a regular column. His play Letters to Lucia celebrating the life of James Joyce’s daughter was first performed in 2018 by the Triskellion Irish Theatre Company.