Dear Bhagya Lakshmi

Vijayalakshmi Sridhar

That day, Appa is in the center of the hall in a box and Amma is huddled in a corner, away from the leather couch she always sits on to paint and listen to music and watch TV and munch on roasted peanuts. Today no music, no painting, no TV, no peanuts. Her life with Appa has come to a skittering stop along with Appa’s battle with his failing liver.

Appa’s brother, his son and wife and a few neighbors are with us. Whoever comes, enters the hall, goes straight to Amma to pat her on her arm, listen to her prattle on about Appa then remind her of the flickering significance of life in general. Truth be told, Appa had died 3 years back when blood gushed out from his nostrils and mouth, and filled the ceramic washbasin he was leaning into.

I wonder if my life which is about to start with Dyan will be different without Appa, in some way. It has been twelve long years since I moved away from the village. As I started mingling with the city folks, making new friends, the distance between Appa and me had widened. It was then that the distance between him and the bottle narrowed.

It is a sultry evening. Hot air rises from the room and the ancient ceiling fan does little to abate the humidity. I see the coconut tree in the compound swaying but the breeze doesn’t reach us. I remember a Tamil poet’s thoughtful verse: Was the branch teased into movement by the breeze or did the movement of the branches generate the breeze? I want to ease my butt off the wicker chair I am sitting. I get up and my hand brushes Dyan’s resting on his thigh. He is startled and rises to accompany me. Amma’s head turns, our eyes meet, her’s opaque from the tears. Her lips converge to form words. I look at her intently, but then she gives up and lets her head drop. I tap Dyan on the shoulder and he sits down.

I walk into Appa’s bedroom where my twin brothers Baskar and Bhanu Chander are talking, with a mass of papers in front of them. Behind them on the wall hanger are Appa’s Singapore shirts. Seeing me my brothers lower their voices. But I ignore them and head to the restroom. In my head, I open a new door and step into it.

Twenty minutes later, I figure out Amma’s preoccupation. It strikes me too. The next time her head turns in my direction I go to her and kneel down, my ears close to her mouth.

“Bhagya …,”she says, her breath touching me like a hot compress. “Check if Bhagya is here yet,” she mutters.

I gesture to Dyan, who springs up like a keyed-up doll. He crosses the hall and steps into the brick-layered compound. Dyan dares crossing the line with me even though he is aware that I do not like being intimate in public. I keep walking even after I realise Bhagya Lakshmi with her white (once gleaming) body and sturdy girth is not there, till I am away from the palm fronds and bamboo poles and plastic chairs and reach the passage on the side that leads to a two-car garage. Where is Bhagya Lakshmi? Where has Pichai taken her this evening? What errand is he attending to?

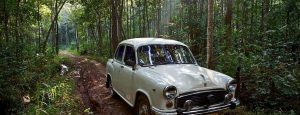

As I begin to piece together what I know, I hear the familiar hoot She was beautiful once, so I look forward to seeing Bhagya’s horn and the curve of white nosing into our compound. I can’t say how glad I am to see our genteel, old Ambassador car right where it belongs. I see my step–mother Swarnam and my step-brother Prahlad in the back seat. The last time I had met them was when Appa was terribly sick and made a ruckus for a glass of drink. The year Prahlad started working abroad Appa had stayed permanently with Amma. Pichai, his eyes bloodshot with last night’s drinking, gets out from the front and with a nod to me, opens the passenger door. I dig deep, my legs two iron poles. I keep looking without a muscle twitching in my face as they get out of the car. Prahlad walks toward me, then changes direction and joins his mother at the entrance.

Alone once again and being the escapist I have always been, I open the door and snuggle into Bhagya’s hot leather comfort.

Appa was known in our village as the ‘Treasure man.” Our house is named the ‘treasure house.’ A water fountain with a lady statue was the landmark our house is known for. Nearly fifty years ago, Appa was said to have come across a pot of gold buried in the backyard. It was about the time when mining as an industry was flourishing in the village. He never discussed it with anyone, not even me but I am told we are richer than our ancestors and the credit belongs to Appa. He bought a white Ambassador and gave it his mother’s name, Bhagya Lakshmi, after investing in a beedi agency and setting up a kirana store in the neighborhood, which bore the same name too.

A new member of the Richie Rich league, Bhagya became his lucky mascot. He travelled in the brand new Ambassador car, dressed in a starched white shirt and dhoti to bring his stock, collect the dues from his small-time borrowers and conduct business in the store.

Appa took care of the car like it was his own offspring. Every morning he would carry bucketfuls of water from the house to wash it. Then with a fiber-free piece torn off one of his old dhotis, he would wipe the front and back and sides so meticulously that the surface was squeaky clean. He drove it with such ease that showed he and Bhagya had a thing between them. Every Sunday he drove forty minutes to Kumbakonam to fill the tank and check the tyre pressure. Whenever he was free, he was always near Bhagya Lakshmi, running his hands along her smooth body, checking for unmindful scratches or functional fall-outs.

On a day when I had missed my school bus, Appa offered to chauffeur me to the nearest stop. We started off already fifteen minutes late. Appa took a short-cut , avoiding the main road, and as soon as we arrived on Veerachozhan Bridge, there was a gurgling noise, a few jerks and the car stopped.

For a moment Appa couldn’t accept the sudden incident. When he came around, he got out of the car and with a thoughtful hand on his chin, he stood on the side and talked to himself. With tension building inside me, I looked at the motorcycles, bicycles and buses that whipped by, throwing a complaining glance at our vehicle which was partially blocking the road. Whenever anyone peered in our direction, I steered away from the window and fixed my gaze on the decked elephant motif that hung from the rearview mirror or at the three measured straight lines of vibhuthi (Appa’s handiwork) with a dot of red kumkum in between on the front.

“Appa! I leaned out of the window and shouted in frenzy. “I have an exam in another half hour,” I reminded him, thinking it would break his soliloquy and push him to do something to get the car moving.

“Hmm ”Appa said in response and opened the bonnet. Did he know enough to fix the problem?

When I got to the front of the car he was the same: hand on chin and inspecting the wired interiors without even touching it. Then he went back, got the coolant bottle and replenished it in the cabinet. He tried starting the car but in vain. He came back and stood there, hand back on chin. ”Is there a problem? “I threw the question about just so he would snap into action. Hopeless; I looked around for a rickshaw. Like Baskhar and Bhanu I should also have moved to the Kumaraguru boarding School in Papanasam.

It was then that I heard those deep-throated mutterings. I looked at the open bonnet to find Appa, his hand and cheek resting on the car’s body, talking to her. Yes, talking.

“Come on Bhagya, fire up. You can do it. Save my face. It is Ahalya’s exam today.”

He kept repeating it, in an appeasing tone, his hand lightly stroking and patting the car. Finally he closed the hood and came around to start the engine. A few turns of the key later, Bhagya whirred to a start. What? Speechless I got in it. Appa deposited me at the school gate five minutes ahead of time.

After that I kept seeing Appa talking to Bhagya, in that soft, honey-coated voice. At times, his voice dropped to a caressing whisper and at other times his face was a kaleidoscope as he communicated his feelings to Bhagya as if through telepathy. But at all times Bhagya submitted to Appa’s loving commands and beseeching requests. I watched him with awe.

“Appa, is she really listening to you?” I asked him one fine day and he guffawed.

“Of course she does. She is a fine lady. We are in love kannu.” Appa winked at me and I assumed Amma was not to be told of this.

I continued to watch him from my bedroom window besides the gleaming Bhagya in the white moonlight, while Amma sat in the hall listening to P. Susheela songs on the radio, her hands deftly moving the paintbrush on the mounted canvas. There were paint tubes lying open about her. She was painting a woman in a lush landscape, walking to a gushing stream with a pot on her head. After each stroke and dab her hands picked the peanuts from a paper packet. Already the house was full of her paintings in the hall, bedroom, the dressing room with her name-Kousalya scrawled on each one of them, the letters standing out like small matchsticks. She kept painting, oblivious to her husband’s love affair with another woman too.

Years later I meet pranic healer Dyan and ask about Appa’s conversation with Bhagya. I tell him I am worried he has lost his mind.

“Every object has some energy,” he tells me in his soft voice, his dense, masculine scent winding me tight. “When the communication is in the same frequency it clicks,” he keeps it short knowing well I will not be sold on the idea yet. But his words stayed with me.

When Swarnam chithi, daughter of one of the small-time suppliers stepped into Appa’s life, he was in his fortieth year, still full of unbridled romance and vigor. In those days rich men having a second wife was not a rarity. Appa married her but since Amma bucked at moving her into our Treasure House he bought another house for her at the edge of the village, in the adjacent town.

Every Friday, late into the night Appa would sneak into Bhagya Lakshmi and drive over to Swarnam’s to spend the weekend leaving Amma and me back at the sprawling Treasure House. Though Amma never showed her anger and disappointment openly to Appa, she carried the wreckage with her. I kept watching Appa, weekend after weekend, losing him bit by bit to chithi, having no idea how to subvert their relationship. My helplessness crushed me.

That summer, when Baskar and Bhanu were home from school and Amma’s parents had come to take all of us to their house for a short stay, I had my first attack of epilepsy. I was carried to Dr. Narayanswamy’s clinic in Kuttalam in Thatha’s car. Amma later told me that Appa had been with Swarnam and her one year old son Prahlad.

“Show him more love Kausalya.” Thatha advised her instead of saying, “leave your painting and music to be with him.”

Two weeks later, I somehow gathered my wits and decided to put an end to Appa’s misbehavior. I knew Amma would spend the night with her painting and music. She had a commission from Saraswati Mudaliar to be delivered the next day. As lightning and thunder broke in the sky, I snuck into Bhagya’s boot and closed it, snuggling into its black, strong-smelling interior. I kept blinking away the darkness as the car bumped over the bridge and then slid down the narrow path beside the bamboo grove and a branch of Cauvery which got redirected to the plantain fields, the same path I crossed every day on my way to school. The light on top of farmer Chinna’s motor house came through the chink in the door confirming to me that we were near Swarnam’s house.

Appa’s newly-appointed driver Pichai opened the door. I heard Appa’s voice dropping low, telling him something in secrecy. I couldn’t hear it in the rush of the rain but knew what it was about; Appa wanted his bottle of alcohol. He had started drinking at home after he invested in Singapore Komala Vilas and travelled by plane. I had heard Amma complaining to Thatha. When Pichai came around to get the umbrella from the boot, I sprang out, like an apparition.

Pichai froze in his spot and Appa shouted at me from Swarnam’s verandah. “How did you get in?”

My eyes fell on the house, a modern structure with its raised platform and a low façade with ornamental curlicues at the edge. The first thought that struck me was that there was no statue; no fountain. I thought of our old, Treasure House which was falling apart, Amma and I caught in its shadowy interiors, and I broke down. I cried my entire body turning into an irretrievable mush, in self-pity and loneliness.

My epilepsy and all, Appa couldn’t bear to see me emotionally down too. So he walked into the rain and led me into the house. We couldn’t get me back to Amma that rainy night because of a power outage Appa telephoned Amma and that night I slept beside the baby crib with the nanny, leaving Appa and Swarnam in the other room. I had made a disturbing discovery that Appa called the baby Laddoo and cuddled him so much. I had to control myself from doing the same to that sweet-smelling, plump bundle.

With Aduthurai Seetharama Vilas’ idli-sambhar lingering on my tongue, I didn’t sleep a wink that night. I wasn’t ashamed of my behavior but after that I stopped addressing him as Appa.

The following year, Appa bought a grey Fiat leaving Bhagya and Pichai for our use. Appa had become a stranger in the house, none of us talking to him. Appa buried himself in work, travelled to Singapore often and the bottle helped him forget the reality. He still kept going away to Swarnam’s at the weekends. Since there was a second car and Pichai too, Bhagya had had a promotion. Whenever there was an emergency in the village Pichai drove the sick and the injured to Kumbakonam or Kuttalam or Mayiladuthurai in the Ambassador. From pregnant goats, calves and roosters to men and women, Bhagya helped many in the village out of a crisis. Leaving her world of painting, Amma helmed the charity operation, drawing some kind of gratification from it.

Mostly Appa was distanced from Bhagya. But whenever he drove Bhagya he was gone for hours. I imagined, he spent his time talking to her in that same wistful tone. Once back home, he was no longer energetic enough to carry bucketfuls of water to wash her; but he couldn’t stand to see her dusty and dirty. So with a cloth in hand he wiped Bhagya till there wasn’t a jot of mud or sand on her white body.

It was a hot, windy day in October when Appa was away in Singapore that we had a call from Swarnam. She had some emergency and needed Pichai to take her to the hospital. Now in her all-new avatar, Amma was ready to help. She called Pichai to hand him the car key and asked what was wrong with Swarnam. Pichai who was Appa’s drinking partner and staunchly loyal to him wouldn’t tell her anything. Finally Amma had to guess.

“Is she pregnant again?”

Put in a tough spot, Pichai shook his head, grabbed the key from Amma’s hand and rushed to the garage.

That evening Amma took her paints and brushes and smudged the walls, ceiling to floor in the living room in big, ugly strokes.

We came to know that Swarnam had miscarried the baby and was in the hospital at Kumbakonam. Pichai had locked the house and brought Laddoo along with him. Amma threw her past out the window, fed and took care of Laddoo. Appa returned a week later to find his son in the hall, paint brush in hand, Amma teaching him to paint and me holding his hand and guiding him. Amma packed off food to Swarnam in the hospital. When Appa wasn’t looking, I kept cuddling Laddoo, pinching his still-chubby cheeks fondly, lightly and with guilt. Baskar and Bhanu stayed away from this spectacle.

All of us had turned a few dizzying corners when he had been gone. But we were not ready to take him back again. Amma and I let the wall between him and we remain. Much to our disappointment, by then, Appa couldn’t care less , he had taken to the bottle and lost his health.

Amma is back on the leather couch in the hall. Her hair is free from the long braid and her forehead is bare, without the coin-size red dot of kumkum.

I cross the dining hall carefully without slipping. The house is washed thoroughly after Appa’s body was carried away. The house is suddenly empty without the teeming people and Dyan. I take a seat on the couch, a bit away from amma, thinking of the distance that has been growing between us all these years.

“I have given the green signal for Baskar and Bhanu to share the assets among you three.” She stops and looks at me. I look away. “Except Bhagya Lakshmi.” She concludes the sentence as our eyes meet, as if expecting me to object.

I want to tell her Appa has made a clear will. The agency and the stores had been long gone. Appa had deposited the money to be shared between my brothers and Prahlad. The house where Amma lives is ours and will be undisturbed till Amma is alive. But Bhagya, Bhagya Lakshmi now belongs to Prahlad. I leave the village without telling Amma about that. The others, including Prahlad decide to maintain the secret.

“Whatever you want ..” I say, hoping the numbness will wear off and grief will kick in.

“I will retain Pichai too.” Amma adds.

“But …”

“He has nowhere to go and I want to continue doing what I have been doing.” She has the last word.

Six months later when I am wrapping up with a client, Amma calls on my mobile. When I try hanging up promising to call back, she says it is urgent. I see off the client and come back to my desk. I lean on the chair, taking deep breaths and get back on the phone.

“There has been an accident.” Amma’s voice sounds feeble.

“What? Where? I told you…”

“Yes the fault was very much with Pichai.” She cuts me short. “No harm to anyone. But Bhagya has suffered damage. And they are not letting Pichai take it back.”

“Oh. So it is a police matter now. I wonder if the insurance papers are still intact.”

“I have them.” Amma is quick on her defense.

In a few hours, she calls me to tell me that Prahlad has come to help her out.

With him working out the finer details I speak to a lawyer in Kumbakonam to initiate contact with the police station and guide Prahlad.

Defiance pushing me, I email my boss a reason for my absence, and book a ticket to the village. Counting the approaching weekend I can afford to spend six to seven days. I leave after writing a note to Dyan.

The car, having run into a truck looks severely damaged. One side needs complete reconstruction. I bring a mechanic to assess the damage and then get it towed to his workshop. I am glad there is still someone around to repair the vintage model.

On the day I am to leave I go to the workshop to check on it. Bhagya’s exterior is now free of the dents. I call out to the mechanic who slides from under her, clear the bill and pay him some extra money too. He promises to deliver the car home in good condition in the next three weeks.

Satisfied, I pick up my travel bag and turn to walk out of the workshop. In a heartbeat, I change direction and go back to Bhagya. Leaving my bag on the floor, I put my cheek to her, the same way Appa had done years back. My hands caress her body fondly.

“Come on. You are not old yet. Pull yourself together,” I whisper, imitating Appa, his face filling my mind’s eye. A knot in me starts to unravel. Soon there will be tears– I know.

![]()

Since young, stories have been part of Vijayalakshmi Sridhar’s world- both telling and listening to. Mostly she writes about people and their relationship angst.