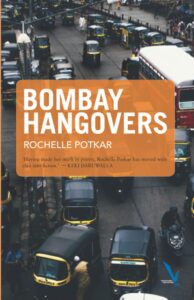

Bombay Hangovers by Rochelle Potkar

Reviewed by GJV Prasad

It is often said that poets are also good writers of short fiction. The short story after all is a prose genre closest to poetry and stories have been narrated in and as poems for centuries. Both genres can be indirect, building up moods, rather than explaining characters or forming them fully, sketch-in events and locations with quick strokes, and depend on the reader’s imagination to help in reading the work, to find their own meanings—to create their own moments. It is textures that you look for, the hidden layers that speak to you in well-crafted short stories. And it is this that you get in the sixteen stories that constitute Potkar’s Bombay Hangovers.

These stories are not a drunken romp through India’s most famous city, nor are they about the aftereffects of such excesses. But Bombay (not Mumbai, you notice) is a city that gets to you, that holds out myriad dreams and fulfils some, that lives in hope that crowded gullies will lead to broad boulevards, that the crowded slums and local trains can and do meet skyscrapers and the world of airplanes and one can make connections across these unseen but clearly felt line and cross over occasionally to the other side. Bombay is the city of unlived lives, of distractions, of boring routines, of exciting possibilities, and treacherous slopes. Most people live out their lives of ordinariness in the midst of possibilities, aware of them. Potkar’s stories explore these everyday lives.

The stories have intriguing titles, and the writer wants us to be active readers filling in the blanks, forging connections, letting our imagination run over the stories she sketches for us. The collection begins with “The Arithmetic of Breasts” (this is a title you don’t have to struggle with), a story about a couple, a mathematician husband and his home-maker wife who had a doctorate but did not take up a career. It is a rather wry story, one that shows how the male gaze works, how a couple fall in love, how their life together weathers the years (they have two daughters), and how they get through the wife’s breast cancer and mastectomy. And how they love each other. And make love to each other. The writer doesn’t judge, doesn’t pass comments, doesn’t give us her opinions. This is one of the ways in which life plays out, she shows us.

In “Parfum,” Russi becomes an expert perfumer and in his desire to create the ultimate perfume, the scent of his woman, his wife, he drifts away from her, not even knowing her routines, and finally finding the real perfume elsewhere. “Fabric” shows us the rise and fall of Kailas, who from aspirations to higher management in the mills ends up as a security guard in a mall after the disastrous strike that saw the closure on mills in Bombay. The story is really about the impact of his life on two women, his two wives, and how it plays out at the end. Other stories explore how various emotions play out in the life of characters. How is one roused to anger? Does it lead to action? What are the complicated emotions that arise with lust, with sex, with adultery? When is adultery exciting? Would a man want to murder his wife and her lover when she seems to be so different with the other man, almost becoming a different woman?

When you write about Bombay, Goa can’t be kept out, as it were. So not all stories in this volume are about Bombay. One is relieved at the ending of “Salad” (a partly Goa story), an intricate short story that could have turned tragic. And when you have Bombay based stories, how can you not have one on Kamathipura, the red-light district? The narrative point of view changes from the third person to the first in the narration of this story, “Mist”, but it is again a matter-of-fact telling, even when it is about to have a fairy tale ending for one of the characters at least. And “Honour,” again a multi-layered story, asks the question about the impact of criminal action of one member of the family on the others (do we think of the criminal’s family at all?). Just like we don’t wonder about the impact of raising an intellectually disabled child, someone who is mentally a child when he has grown to adulthood, on the siblings and parents. Turn it into sibling and parent and you have the story “Noise.”

Potkar is interested in showing us what it takes to live certain lives in certain spaces. All the stories have women playing significant roles, though it is not only women that Potkar is interested in. How do women cope with trauma, with the particular fate that seems to characterize the urban patriarchal jungle – molestation and rape? Bombay allows her a place name that can be seen as particularly apt (“Andheri”) for such a story. How do people cope with bullying – is school, in the workspace, in the residential community? What does it take to stand up and carry on even better than you had done before (read “Paranoia”)? And what is the impact of domestic abuse on the others in the family (“Slice”)? A curious story ends the collection. It is based in 1857, the year of the First War of Indian Independence (or the Mutiny). It ends with an act of personal mutiny, an act of independence, which seems particularly apt in these times.

You may think that these stories could be from anywhere, but Potkar anchors them in the topography of Bombay – in specific areas and communities. “Euphoria,” for instance, is a Bombay story – nowhere else in India could you imagine the three characters who get together getting together at all. The really short short story “Our Lovers” could have been set anywhere but Potkar anchors it to Bombay brilliantly. Bombay Hangovers is a collection meant to be read one story at a time, to be savoured slowly, so that one can think of people we know and stories of we don’t know but we inhabit.

![]()

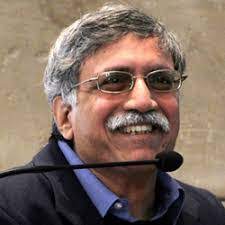

GJV Prasad, formerly Professor of English at Jawaharlal Nehru University is a poet, novelist, and translator. His teaching and research have focused on Indian English literature, modern drama, and translation. His recent publications include four edited volumes – Violets in a Crucible: Translating the Orient (co-edited with Madhu Benoit and Susan Blattes), India in Translation Translation in India, and Disability in Translation: The Indian Experience (co-edited with Someshwar Sati), and Reading Dalit: Essays on Literary Representations– and a short monograph on Khushwant Singh. His latest publication is a translation of Ambai’s stories, A Red-necked Green Bird.