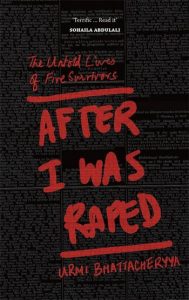

After I Was Raped by Urmi Bhattacherrya

Reviewed by Kinshuk Gupta

In a society that shies away from sex education and affirms boys’ aggressive sexual presence through irresponsible media portrayals, many boys grow into adulthood thinking that forcing themselves upon resisting women is normal. It is thus that India tops the charts of unsafe countries for women, as we continue to hear about countless incidents of sexual abuse every day. As is often reiterated by professionals working on these issues, these snippets of news comprise only a small percentage of the actual cases that often go unreported because of families worried about their social prestige and the inadequacies of the justice-seeking machinery.

Although one of the major constituents of crime in India, sexual abuse, is the hardest and trickiest to understand. This, I believe, is an important reason why a lot of writing has been happening of late, around the subject matter; an attempt to deconstruct the complexities involved. On the vague understanding of the crime, Sohaila Abdulali writes in her book, What We Talk About When We Talk About Rape, that:

It’s the only crime to which people respond by wanting to lock up the victims. It’s the only crime that is so bad that victims are supposed to be destroyed beyond repair by it, but simultaneously not so bad that the men who do it should be treated like other criminals.

We tend to think of sexual abuse in terms of a crime; our thinking has moved little beyond the causes and motivations. We are ready to dress the survivors in the armour of boldness and are always at loggerheads with society and law to seek justice.

Urmi Bhattacherrya—a former Gender Editor at The Quint and recipient of UNFPA Laadli Award for Gender Sensitivity—in her debut book, After I Was Raped, moves beyond the hackneyed tropes on rape. She tells compelling stories of women who have been brutalized not only by their perpetrators but also by the law that has exacerbated their suffering.

Narrating the stories of five women—a four-year-old girl, two Dalit women, an eight-month-old infant, and a young professional, she grapples with the hard question of where does rape end? In the foreword, she observes:

Media messaging will tell you it ends in the silhouette of a single frosted palm cutting its way down a glass pane. It will tell you it ends in a news bulletin about a ‘Woman, aged X, raped by men or a man, aged Y’—with the aforementioned women never to be heard of again.

On the surface, the premise of these stories is pretty similar, even clichéd, but what sets this book apart is Bhattacheryya’s compassionate tone. Even while reporting these stories, trying to reach to the core of the truth, her writing never feels matter-of-fact, rather is rich with details that deeply move the reader. She writes about Smita who got raped by her lover, now oscillating between love lost and self-loathing thus:

Plans with Smita hinge on a fulcrum of variables – how “safe” or “dangerous” a certain cafe, metro terminal, or local watering hole feels to her; whether a certain item of food served by an unsuspecting bearer will potentially trigger a memory or elicit a sob; and whether she can return home by sundown or before her parents chastise her for being “out” – whichever comes first.

Another important aspect that I particularly liked about the book is that it doesn’t end with the story of survivors. Bhattacheryya tries to investigate the reasons for delayed justice or no justice at all. Narrating the story of Nidhi, an eight-year-old, who was lured away by a bhaiya and later raped, she talks about the insipid judiciary:

Sometimes the judges are on leave. Then there is large pendency of cases. You don’t get frequent hearings to present your case—so much so that sometimes if you miss a hearing, the next one might be a year later.

The pervading hostility in the courts, which relies blindly on facts, comes across multiple times in the book—the two-finger test designed to check sexual habituation; questions about sexual history; prying eyes of men attending the hearing. She also talks about women lawyers, who despite being determined, are unable to provide justice to the victim, and themselves suffer variously.

Kataria spoke of incidental trauma latching onto the body, mapping itself as myriad physical ailments…That second-hand trauma becomes a part of you.

Often it is assumed that rape ruins lives, that women shattered by it will never have a semblance of normal life. However, Bhattacherrya, through her sensitive portrayal and humanistic approach, tries to affirm that despite rape being a defining memory in one’s life, it is not the end of life. And precisely not the way one wishes to be labelled for the rest of their lives.

As Anubha Bhosle writes in the blurb: “this book shatters the silent heroism of survivors—a myth we love to perpetuate. This book, a voice of survivors as called by Bhattacheryya, actively questions the broad rubric of patriarchy and misogynistic mindsets that are eager to relegate the victim to a guilt-ridden, hopeless life. One cannot afford to miss reading it.”

![]()

Kinshuk Gupta uses the scalpel of his pen to write about his experiences as an undergraduate medical student. He was longlisted for the People Need Change Poetry Contest (2020) organized by The Poetry Society, UK. His haiku have been nominated for the Touchstone Awards and the Red Moon Anthology. His work can be read or forthcoming in The Hindu, Modern Haiku, Haiku Foundation, Contemporary Haibun Online, among others. He currently works as the Poetry Editor for Jaggery Lit.