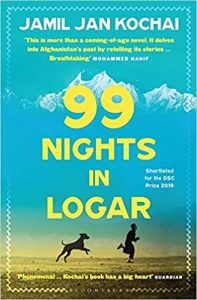

99 Nights in Logar by Jamil Jan Kochai

Reviewed by Samreen Sajeda

It was odd, I thought, how a few miles could turn bombs into lullabies.

-Jamil Jan Kochai

The very first chapter of 99 Nights in Logar is titled ‘On the Thirty-Second Morning,’ prompting a prediction: this novel is going to break the monotony of a linear narrative. True to that, the novel evolves into an intricate narrative pulling the past into the present through good story-telling that illustrates the rich culture of Afghanistan, with the subtle yet lingering ache of migration.

Just the chapter titles are intriguing documentations of days and times, echoing diary entries. Although the first part of the novel revolves around the speaker, Marwand and his gang—Gul, Dawood, and Zia walking “deeper and deeper into the valves of the country” in search of Budabash, the lost dog, the novel is in no way limited to narrating that adventure.

The story is set in 2005, when “the American war was sort of dozing, like a coma.” Yet it constantly looms in the background like the “the distant chatter of artillery.” Even as the children “plopped toot” in their mouth, they “picked at the old bullets stuck in the bark.” This juxtaposition of antithetical images run throughout the narrative as though the mind constantly strives to balance the terror with flashes of beauty such that, even as Marwand and Gul spoke of Watak Kaakaa’s execution, ‘white lilies fell from the chinar, scattering on the water.’

Women are prominent in the novel, like the “mother, who, during the course of the war, had learned to patch up bullet holes,” or little Miriam who plays a vital role in supervising her cousins as they nurse their elders falling sick at the same time (magic realism, reading that bit at the time of COVID-19 had its own resonances). Abo, seems to have a stronger say in matters of the household unlike in most patriarchal families. Nabeela khala’s “little dress shop started netting a tidy profit” and although Moor is heard less often than Agha, her words demand immediate attention whenever she chooses to speak. This is made emphatic as their son prays “for her mind and his body.”

The novel complicates the idea of oppression. One of the most poignant scenes is when little Marwand along with other kids decides to pelt stones at the butcher’s son—

There came this moment between the holding of the stones and the ambush itself, when I was watching the butcher’s son walk the road,…knowing what he didn’t know,… and I felt so bad for him and for me too, Wallah, because although I knew that the stones were coming, I didn’t know why, and in that way me and the butcher’s son were the same.

This dilemma is a profound metaphor for the entangled relationship between the oppressor and oppressed, the Occident and Orient, or America and Afghanistan. For ironically, in the absence of the oppressed, the oppressor would cease to be.

A collective struggle shrinks the distance between the homeland and the host country. When Masoom informs Agha “of what was going on with his own family (certain things were always left out: the failing crops, the lost toe, the bruised face…)” On the other hand, the reader is also given a glimpse of the situation back in America—“My father worked. From six in the morning till seven at night, he hauled barrels of pesticide, drove trucks, and landscaped the lawns in white neighborhoods. Weekdays, weekends, and holidays too…How hard he tried not to be broken, not to break us,” thereby hinting at the perils of a forced migration, as the oral narratives become a route to remind the younger generations of their Afghan roots.

Kochai unsettles the reader by magnificently documenting the Afghan tradition of story-telling. There are numerous stories strewn across the main narrative. Mealtimes become an occasion for the entire family to sit together and share bowls of chicken shorwa while sparking stories narrated to the “children of her children, to ease the tension, or to teach a lesson.” Paradoxically, along with the reader, the speaker himself becomes a listener, scripting the oral word.

Language spills over cultures as Marwand’s relatives try to communicate with him in “a butchered mixture of English, Pakhto, Farsi, and sign language.” Native words are sprinkled without italics, making it a hybrid tongue. There is a fine blend of humour even in the most unexpected scenes—“Agha bit down on his lower lip like he always did right before he smacked me, but I kept on eating, quickly shoveling small bites into my mouth…He wouldn’t hit me with food in my mouth.” The prose is poetically rendered. There is a quirkiness in metaphors—comparing green eyes to duck shit, pink sores to blossoms, or the long white scar to a stream. These comparisons are like conceits and make the reader take a pause to marvel. Often, paradox adds to this literary feast, like when Marwand and Zia lie in order to “stay true” to their word. Most importantly, the novel ends with the story of Watak Kaakaa’s execution, in Pakhto, untranslated; as if in homage to the oral word. This aesthetic and experimental use of language is also the reason why one feels that the narrative voice is too articulate and intelligent to be a twelve year old’s, perhaps not if he grows up into becoming a writer.

Kochai’s stories preserve the timeless space between love and loss while not being oblivious to the futility of war. After all, ‘it hurts to hold a gun.’ What makes it even more unique is the glowing faith the characters cherish and the promise of returning ‘home’, ephemeral and eternal.

![]()

Samreen Sajeda graduated in English literature from Sophia College, Mumbai. Thereafter, she completed an MA in the same discipline from the University of Mumbai. She is, at present, reading for a PhD in Palestinian poetry in translation. She writes poems and, occasionally, short stories. She is also interested in photography. Her work has been published in the Indian Cultural Forum, Muse India, Spark, Hakara and, the anthology of Poetry India (2017).