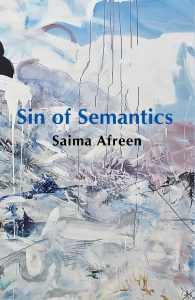

In conversation with Saima Afreen on Sin of Semantics

Interview by Poornima Laxmeshwar

Saima Afreen is an award-winning poet who also works as Deputy City Editor with The New Indian Express. Her poems have appeared in several Indian and international journals. She received ‘Writer of the Year Award, 2016’ from Nassau Community College (the State University of New York). She has been part of several literary festivals and platforms. She’s been awarded the Charles Wallace India Trust Fellowship (2019) in Creative Writing at the University of Kent, United Kingdom. In the autumn of 2017, she was awarded the Villa Sarkia Writers’ Residency (Finland), where she completed the manuscript of Sin of Semantics. This is her début poetry collection.

Saima spoke to Poornima about this collection of poems, the socio-cultural events that became reasons for the poems and the personal narrative that describes the journey of writing.

“For a Child of Kashmir”– This poem is excruciating. Why did you choose a child in the poem? Is it because to think of children suffering is unbearable or because you feel helpless about their failed dreams??

I wrote that poem after the 2010 Kashmir unrest which saw the crackdown on unarmed civilians who were protesting. Most, among the brutally killed, were youngsters. Now, after 72 years of conflict, the right-wing extremists and citizens with ‘similar tendencies’ are blindly celebrating the brutal decision of scrapping Article 370, bifurcating the state, and making it a Union Territory. This is coupled with the unimaginable communication blackout (rightly called collective punishment of the people of Jammy & Kashmir by the United Nations’ Human Rights Council) in the valley. The blinding pellets shot at children weren’t enough already! How does a little child of five make sense of this tyranny? To see thousands of children suffering like this. How agonizingly disturbed their childhood dreams must be! What must be happening to their tender minds? The unborn witnessing the ghastly events unfolding from a womb face the worst! Kashmir is bleeding! Its children are being erased and denied a happy future! No poem is enough to pen their pain!???

Tell us more about this poem Are You the Wolf Who Stood at the Edge of a Fairy Tale. I am so fantasized by this title, that I wanted to prompt you to share more about it.

In this, the only life (to rephrase Kathleen Jamie a bit differently), we all are standing at an edge overlooking the bottomless pool of dark twinkling water waiting for a goblin, a winged creature or that furry animal to hold our hands, uproot our feet and take us to their land through the creases of a pulsating map. We forget that we are the fairy tales in flesh. Each moment adds a new vowel, a new semicolon. As a child, I often found myself in those Russian books of Princess Vasilisa and mysterious forests. My father had bought the illustrated collections for my elder sisters. Later they were passed on to me and younger siblings. It all looks so distant, so dreamy. As an adult you are secretively more in need of those stories; during sleep you search for that wolf, perhaps from the North, to stand by ‘your fairy tale’ and guard everything that whispers under your skin. The night watch begins. The tale within tale spins.

When I read your poems, I feel like I am reading a prayer. I sense that your style has a rich blend of gorgeous images and social issues with such an easy duality. Do you consciously choose the images and arrange them, or it all comes with the flow?

I believe that whatever we speak, think, and write derives its sap from the said and unsaid floating between the layers of socio-political undercurrents. That’s the grammar underneath. An artist/poet sees what others can’t. A poet holds eternal apprenticeship to Life and its endless ledgers, filling the unmarked boxes with lilt and light. What spills over is poetry. And in this bright pool images find their way as do the direct and indirect experiences culminating into a concoction–a mix of elements which surprises you.

As a journalist, I get to meet several people, hear their stories, get acquainted with the environments both gory and pleasant, surprising and damning. I filter information and what remains as residue finds companionship in what I think as a poet.

The photograph of the dead body of the three-year-old Syrian boy, Aylan Kurdi found on seashore still haunts me as does the 2018 report by a monitoring group on death count in Syria which says that 367,965 Syrians are dead, leaving out the 192,035 people who have been missing! Combine the two and it’s a big number! Back home many civilians in Kashmir are missing or presumed dead, and we don’t even have the exact numbers!

This book of poems is your work spread across the years. How do you think your writing has evolved over time?

We are all works-in-progress, and poetry as our accomplice experiences everything that the mind and body go through. ‘Sin of Semantics’ is my debut poetry collection. The poems in the book encompass the timeline of more than ten years. I re-write, edit, rethink a lot allowing myself to soak in the words, their arrangements, placements, and context. If an idea doesn’t magnify itself or loses its connection with me, I let it fly. If it comes back with something more to tell, I welcome it to my notebook otherwise I set it free forever.

The poems “A Couplet” and “The Charpoy My Grandma Left” is all about roots. Please tell us what makes you go back to them?

Both the poems tell tales seen from the eyes of elderly family members. The images summon you to explore the wide, wild jungle of times gone by which have altered the topography of hearts and lands and every related conversation is a revisit to these months, years, decades. A rendezvous to what was, reintroduction to where you come from. The timbre in the stanzas calls to the roots coiled within you… It summons the courage to turn back to see that no song can repair the wrongs of history.

The grandfather and the grandmother in ‘A Couplet’ and ‘The Charpoy…’ aren’t related to me though during Partition and the 1971 liberation war in East Pakistan (Bangladesh) my family lost members, land, property and more. The stories in the poems are of other people with similar or worse losses which have overlapped with my family history. I can sometimes hear the swish of my grandmother’s sari when she had to run out of her haveli at midnight as communal riots broke out. Or how the birds she released from the cages would always come back to the giant courtyard for food not realising that they were set free from a divided land to be forcibly forsaken by its denizens.

There are cities in your poems and the reader is shifted into a different space altogether which is a beautiful experience. Do you carry these cityscapes with you even after moving and turn them into poems?

“Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears,” wrote Italo Calvino. And we carry them in our bloodstream, witness their rise as their glassy moulds hold our silhouettes, secretly smuggling a part of us in the plank of a staircase, a rusted gate or in the reflections captured in the windows of a tram. The left-behind parts of us live and breathe on their own. The cities claim the lacunae as miniature versions of their own deposits. Their walls, sounds, scents, chill, streets, teacups, bridges along with everything else inhabit the landscape of our language. Without them, you feel you are carrying an empty river. They walk with you to more cities, new countries making colonies within your words growing as lush harvest. It’s the result of the mutual exchange between you and the cities. The equation keeps growing.

Do you ever feel that a poem you’ve written is complete?

Never. Paul Valery didn’t say for nothing: “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.” The published poems haunt you; their shadows knock at the door of the editor within you. You don’t allow entry and feel suffocated. Virgil wanted to rise from his deathbed and burn his epic poem ‘Aeneid’. Nikolai Gogol had burnt the part of his masterpiece ‘Dead Souls’. We all want to destroy what we have created thanks to perfectionism, the need to edit and re-edit is a never-ending temptation!

Then there are poems on lilies, tea, rivers, smell and everything so ordinary. Do you think as a poet anything and anyone could become a muse?

Everything, in its entirety, lives and breathes. I am talking about the energy an atom contains whilst it’s a part of red brick, a wooden banister or just a knife holding an eclipse in its silver. Even the inanimate get awoken to soak in everything around it. And no, it’s not Morse Code. It all opens up, blooms right in front of you ready to be dissected, studied, connected with. One just needs to feel it. The air then smells of the season, the object, which catches your attention ready to invest itself in words. Then comes the open anthology of everything alive and growing–they magnify themselves, almost imprinting on the mind. If you see a single green clothespin on a coloured string under a rain spell, it becomes an enigmatic canvas holding so many possibilities. Flowers, water bodies and birds are already complete works of art; poets just pilfer from them.

What do you suggest is important for aspiring poets to know?

That you shouldn’t run after finding ‘your voice’. Instead, your craft demands more of your time, more finesse. As you progress in your writing, the words tend to set to a pattern and that definitely isn’t a voice. One needs to sit amidst words and interact with them gently observing their structure, placement, and volume. Haste just destroys it all even if you are writing an angry poem or a proud one.

![]()

Poornima Laxmeshwar resides in Bangalore and works as a content writer for a living. Her poems have been published in national and international journals of repute. Her first poetry collection “Anything but Poetry” was published by Writers Workshop, Kolkata, a chapbook of her prose poems “Thirteen” was published by Yavanika Press and her full-length poetry collection ‘Strings Attached’ was recently published by Red River.