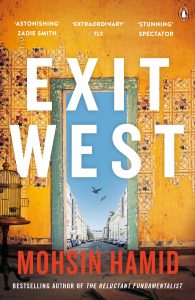

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Reviewed by Mary Ann Koruth

Doors appear in a world swarming with refugees, a world already changed and marked by their certain presence on today’s global landscape. Dark doors, doors that seem impossibly deep, doors that frame the end of mysterious passages as fraught as the birth canal itself, magical doors that appear for no reason than to transport refugees willing to be reborn and recast into better, safer, newer lives. Doors that bend time, delivering human beings from war-ravaged Somalia to the island of Mykonos in Greece, from Sri Lanka to Dubai’s shopping district, and so on.

It is a solution that can only exist in the imagination, and Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid employs it with great artistry in the 2017 novel Exit West. Framing and weaving a story inspired by the horror of the global refugee crisis, the novel’s two protagonists, Nadia and Saeed, live in an unnamed city in an unnamed country, watching, as it is taken over by militants. I have often wondered what it must be like for ordinary people to eke out ordinary lives in cities that grow increasingly dangerous. By omitting all political detail, yet providing enough references that impel the reader to make the necessary connections, Hamid creates a picture in my mind of the careers and talent lost in Syria’s post-war ghettoes, of dreams abandoned and babies born when Kabul and Pakistan’s Swat valley fell to the Taliban, and Mosul to ISIS. And though Hamid’s disciplined omission of real-world detail only broadens the universe he has etched, Nadia and Saeed’s city is clearly an acknowledgement of the instability that Pakistan often teeters on. So much so, I wondered if the city they were escaping was the Pakistan of Hamid’s worst nightmares.

Nadia and Saeed seek out a door, to escape their besieged city. Exit West is the story of their journeys. Interspersed in their wanderings are glimpses into the straggling lives of other migrants and escapees, only these individuals are nameless and anonymous. A ‘woolly haired’ and dark man in Sydney. Two fragile, thin children with parents who wander the streets of Dubai, appearing to be ‘Tamil.’ Another, a family of translucent, light skin and hidden wealth in a tent in a camp. Appearing at points throughout the novel, Hamid executes these emotional portraits of strangers in a quasi-journalistic voice. Their stories are culled out, appearing like buoys throughout the narrative, bobbing up and harking to the ‘lives of others’, stories that neither Nadia nor Saeed are privy to. They are episodic, tearing the reader away from the reverie of the main storyline, and so attesting to the novel’s primary concern, the human condition. To be a refugee, is to be orphaned – of home, of country, of rights.

From the very start, I was struck by the authorial voice. It is omniscient and poetic, with long, meandering sentences capturing its characters’ every nuance, and nearly biblical in their style and formality. Its effect was to stay with me in the hours after I completed the novel; I felt steeped, perhaps a little hungover. The novel struck a chord, both artistic and emotional. A reference to Silicon Valley in relation to its home county of Marin is mystical because though the valley is left unnamed, its description hovers, liminal, and geographical fact is just another ever-present cloud in the reader’s consciousness.

“…that realm of giddy technology that stretched down the bay like a bent thumb, ever poised to meet the curved finger of Marin in a slightly squashed gesture that all would be okay.”

All fiction is a door, designed to deliver us to new worlds. Hamid has erected very different worlds for his characters; where Saeed is devout and seeking the home he left behind, Nadia, his lover, freewheels into the world with an instinct for self-preservation that she has carefully cultivated. Clearly, Hamid prefers Nadia over Saeed. It is with her outwardness, her embrace of life, of the consequences of her decisions, of her mettle, that he, her creator is enamored. She is a pioneer in a world where the stakes lean in favor of people like her; she seeks out a better life and does not look back.

“I am pro-migrant,” Hamid said, in an interview that followed the release of Exit West. Yet the story explains the tribalism that drives society; Saeed possesses this tribalism, like the very communities where he seeks refuge but would keep him at bay. It is foreign to Nadia, who stands only for herself. In the end, it is just one of the forces that tugs at their bond, distinguishing them as individuals and as migrants who travelled together.

![]()

Reviews Editor Mary Ann Koruth’s writing and reviews have appeared in The Indiana Review, The Rain Taxi Review of Books and The Hindu. She has written for TheAtlantic.com while interning as web editor, and has covered art and culture for other publications.