A Feast of Serendib: 10 Things You Might Not Know about Sri Lankan Food

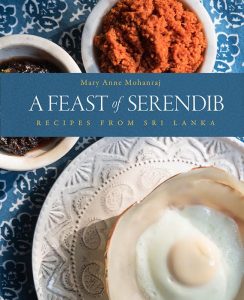

Our founder and original editor-in-chief, Mary Anne Mohanraj, has just launched the Sri Lankan cookbook she’s been working on for the last four years, A Feast of Serendib. Ethnic cookbooks serve as online archives of deep cultural knowledge, bringing history and memory together with essential daily domestic practices that shape human lives; in particular, they often reflect women’s wisdom, and aspects of identity that are too often neglected in more standard histories.

In writing and publishing the cookbook, Mohanraj (an English professor in her day job) had to delve deep into research. In the process, she learned quite a few things about Sri Lankan food, and also learned that much of the world wasn’t familiar with her home cuisine. So, here’s a little sampler she put together.

*

10 Things You Might Not Know about Sri Lankan Food

- Sri Lanka (previously Ceylon) is an island nation that sits near the southern tip of India, a little north of the equator. It’s about ten times smaller than Texas, and has almost two-thirds as many people as Canada. They cook a lot 🙂

- Sri Lankan food is a cross between South Indian and Thai in flavors and approach, with influence from several other cuisines: Dutch, Portuguese, British (all colonizers), Chinese, Malay, Middle Eastern, and more, much as you might expect from an island at the nexus of trade routes. Many of our recipes celebrate a tropical island brightness of flavor.

- Sri Lankan food doesn’t have to be spicy! Many dishes have no chili heat at all (such as our ‘white’ curries), and even the ones that do typically use red or green chilies can be adjusted to your preference. My recipes suggest the amounts of green chili and cayenne that are typical in the region, but you can reduce those further, or eliminate them entirely if you like, and the dishes will still be delicious. (The only exception I might recommend would be for the few ‘deviled’ dishes and katta sambol — those really are supposed to be hot.) And if you like heat, but can’t do capsaicin, try swapping in peppercorn. (I use about 40 Tellicherry peppercorns in my tangy black pork curry, and like to chomp them whole.)

- You don’t have to build a large Sri Lankan kitchen shelf to enjoy our food. When I was a very broke grad student sustaining myself on $20 / week for groceries, I started with just cumin seed, mustard seed, turmeric, and cayenne. Along with salt, vegetable oil, milk, and onions, that’s enough to give you the basics for a meat, fish, or vegetable curry, and I pretty much ate that every night for years. Mackerel curry with red rice = cheap, nutritious & delicious. (If you can afford to pick up cinnamon, cardamom and cloves too, plus garlic and ginger, that’ll add a big boost of flavor. And then the next step, our dark-roasted curry powder…)

- Ingredients aren’t hard to source, especially via mail-order; Amazon carries Sri Lankan curry powder, though if you have the time to make it yourself, that adds a gorgeous freshness. (Note that the curry powder shipped from Sri Lanka will typically have cayenne mixed in, so may be spicier than desired; use with care.) In some American cities, you may even find fresh curry leaves in the grocery store these days. You can freeze them and pull out a stalk or two as needed. (But if not available, dried will do; just use a little more.)

- Sri Lankan food doesn’t use much dairy; while we do use ghee, vegetable oil is often used as well. While you may be familiar with the cream or yogurt-based curries of northern India, in Sri Lanka, we prefer to make our curries with coconut milk. (You can experiment, though; I’ve successfully made Sri Lankan curries with cow milk, goat milk, soy milk, and almond milk…) So if you’re lactose-free, this is a very friendly cuisine for you!

- You might think that as an island nation, seafood would be eaten everywhere, but while it’s prevalent on the coasts (and Jaffna crab curry is one of the world’s finest dishes), seafood is much less common inland; there are lots of Sri Lankans who don’t eat a lot of fish. (More for me.)

- Sri Lanka is very vegan-friendly; since about 70% of the population is Sinhalese Buddhist, that naturally leads to many vegetarians who enjoy a richly varied cuisine. And since, as I said, we tend to default to coconut milk instead of cow milk, much of the food is vegan by default. It’s super easy to cook Sri Lankan for my vegan friends, putting together a complex and varied menu to delight their palates.

- There are nonetheless plenty of chicken and meat dishes on offer, especially since there’s a significant Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and ‘other’ population (about 30%); Sri Lanka has been a multi-religious & multi-ethnic society for more than 1500 years. Dutch-influenced beef smoore would be my recommendation for a spicy, savory roast to impress a crowd, and chicken curry (kukul mas) is eaten all over the island.

- Finally, if you’re gluten-free, rejoice! Sri Lankans traditionally ate a rice-based cuisine, and when you try our red rice, you’re going to love it — a nutty, dense, and flavorful option. I like to mix it half and half with white rice for optimal flavor along with great nutrition. Our bread-y items were also traditionally made with rice flour, though wheat flour does make the end result a little softer, so many cooks do a combination of the two, and some have switched over to wheat flour entirely. So if you’re travelling in the region and celiac, do be careful and ask what kind of flour they’re using.

(I know this sounds like I’m saying we have it all, but when it comes to food, we kind of do 🙂 )

*

A Feast of Serendib is available in hardcover, paperback, and ebook forms, both online (it’s an Amazon bestseller in Indian Food, Cooking, and Wine), and in bookstores and libraries throughout North America. We hope it gets picked up worldwide! If your bookstore or library doesn’t have it ordered yet, putting in a request is always a great idea. Try some recipes at her food blog, Serendib Kitchen.

PUBLISHER’S WEEKLY starred review: “Mohanraj (Bodies in Motion), a literature professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago, introduces readers to the comforting cuisine of Sri Lanka in this illuminating collection of more than 100 recipes. Waves of immigration from China, England, the Netherlands, and Portugal influenced the unique cuisine of Sri Lanka, Mohanraj writes, as evidenced by such dishes as Chinese rolls (a take on classic egg rolls in the form of stuffed crepes that are breaded and fried); fish cutlets (a culinary cousin of Dutch bitterballen fried croquettes); and English tea sandwiches (filled here with beets, spinach, and carrots). With Sri Lanka’s proximity to India, curry figures heavily, with options for chicken, lamb, cuttlefish, or mackerel. A number of poriyal dishes, consisting of sautéed vegetables with a featured ingredient, such as asparagus or brussels sprouts, showcase a Tamil influence. Throughout, Mohanraj does a superb job of combining easily sourced ingredients with clear, instructive guidance and menu recommendations for all manner of events, including a Royal Feast for over 200 people. This is a terrific survey of an overlooked cuisine.”

Ordering Information

- 978-1-64543-275-3 Hardcover (distributed by Ingram)

- 978-1-64543-377-4 ebook (on Amazon, etc.)

- 2370000696366 (trade paperback; only available directly from me, at Serendib Kitchen site; you can also buy the hardcover or ebook there)

Review or Buy It Here (reviews are hugely helpful in boosting visibility!):

Join the Cookbook Club:

If you’d like to support the development of more mostly Sri Lankan recipes, Mary Anne would love to have you join the cookbook club at Patreon — for $2 / month, you’ll get recipes delivered to your inbox (fairly) regularly. For $10 / month, you can subscribe for fabulous treats mailed to you! (US-only)

Foodie Social Media: