An Interview with Meenakshi M. Singh, editor of ShetheShakti anthology and founder of SheTheShakti Inc.

In Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s famous dance drama ‘Chitrangada’, the indomitable warrior princess of Manipur, Chitrangada introduces herself to her love, Arjun through these following lines: “I am not the one you hail in the alter, worshipping, nor am I the one you keep behind you, in negligence. Recognize my essence while you keep me beside you always, in your bounty and amid deep hours of crisis, allowing me to be a true partner in your life’s journey, a true accomplice in your missions” (translated from the original Bengali). While browsing through the pages of the bilingual poetry anthology ‘She the Shakti’ (Authorspress, 2017), I felt the resonance of these lines, which conveyed to me the quintessential spirit of womanhood.

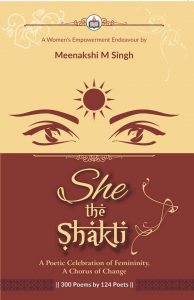

In this collection of 300 poems in both English and Hindi, composed by 124 poets, both women and men, the editor Meenakshi M. Singh, an award-winning poet and REX Karamveer Chakra Awardee brings to the fore the spirited, lyrical voices that empower womanhood through the potent medium of poetry. The anthology builds a discourse around the concept of equality of women through a unique poetic collaboration spearheaded by Meenakshi and her organization “SheTheShaktiInc”, a women empowerment center that she founded in 2017. The poems and prose-poems collected celebrates this concept of equality of women, which had long been denied by the power dynamics of a patriarchal social structure. Meenakshi writes in the foreword to the anthology: “It’s time that history gets created by female gender and history is written fairly. Where female is the main protagonist. It’s time for that change.” In an intimate conversation with her following the publication and critical acclaim of the book, we talk about her inspiration behind this publication and her mission and vision behind her enterprise SheTheShaktiInc.

Lopa Banerjee: Hello Meenakshi, in the foreword to the English section of the mammoth and timely anthology ‘SheTheShakti’, you write a poem with a rhetorical question: “Do the pens have a gender? /Is it that the ink flows better through a man’s poem?” Would you say these questions that bubbled in your poetic psyche ushered in a womanly deluge where other voices joined in, which resulted in this anthology?

Meenakshi Singh: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Lopa, if we reflect any of the historical epics, or literary work of significance in the past, there is not much presence of a woman’s voice. The protagonist is always a man. I doubt that there was any dearth of thinking women in past. It’s natural for any human being to claim their freedom through expression, so I believe the subjugation was imposed on women as a mandate; it was all patriarchal conditioning.

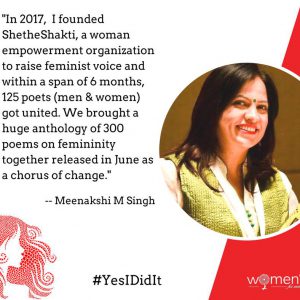

This fact has really compelled me to claim an equal ground and to change the history for the future. Shetheshakti has emerged like the lava as if it was there, ready to erupt. I had never expected that an idea of mine could turn so grand that it would engage 124 contributors so actively, to celebrate the spirit worldwide. The huge anthology took birth in just 3-4 months’ time without any sponsors or a big team backing it. I still feel overwhelmed from the tremendous response from contributors, including you, raising a woman’s voice in the patriarchal society. I believe that it’s some supreme power that united us all to bring the muted voice of woman to the fore.

I believe that the claim to equality which is at the core of feminism needs to be celebrated and voiced, regardless of gender. The time has come to unite in this collective sentiment. It’s as beneficial and important to be gender sensitized and perceive the world equally for a woman as well as for a man.

Lopa: The blurb of the book describes it as a ‘‘grand poetic celebration of femininity.” As an award-winning poet yourself, what has been your vision and mission behind celebrating the spirit of woman empowerment through the medium of poetry, which mainstream publishers generally refrain from publishing?

Meenakshi: I always perceived woman as a powerful being, as a creator (Janani), rather than a victim and thus envisioned ShetheShakti as a celebration of feminists. ShetheShakti was never objectified as an anti-men or an outcry project of sulking/blaming men. It’s a statement of power of the dissenting woman, embracing the spirit and importance of both the masculine and feminine.

I chose poetry as my medium to empower woman’s voice as personally, I have spoken most of my truths through poetry. Poetry heals, liberates and empowers and so poetry is an important armor of Shakti. Poetry has enabled me to feel enough and thus I came up with a book in 2016, “I am Enough” which was a tribute to womanhood. I have benefited from poetry to carve out an identity and received respect in society through poetry, so I truly believe in the power of poetry and know that poetry could be instrumental to change the fabric of the diasporic society. And hence, I chose poetry to fulfill my mission of an egalitarian society.

Lopa: What kind of societal change do you envision from the production of such a collaborative project?

Meenakshi: ShetheShakti did prove that it was the need of the hour, and therefore numerous people united with this cause. I must confess that I received many requests after the anthology launch to bring a second edition. I express my humble gratitude for AuthorsPress publisher and Director Sudarshan KCherry ji, who stood like a pillar for this cause. Also I express my heartfelt thanks to the volunteers Aparnaa Laxmi for being the co-editor, Samrudhi Dash, Simran Arora for her enthusiastic efforts in the compilation and graphical posters, Mahima Sharma for spreading the spirit out and loud. I also want to thank eminent poet Chitra Desai for writing the foreword in the Hindi section. I want to thank the male poets especially Dilip Mohapatra Ji to join this celebration of feminism and make it an all-inclusive project. My humble gratitude to each and every poet who came forward and joined this chorus of change.

Lopa: The themes of gender and sexuality, the feminine identity, the theme of repression of the woman in patriarchy have evolved a lot over the ages, and across cultures and continents. Which feminist poets/authors and artists do you draw inspiration from, if any?

Meenakshi: I have been influenced by many feminists but especially the voices of Maya Angelou, Virginia Wolf, Anais Nin, Coco Chanel, Chimamanda Ngozi have liberated me and empowered me. I feel amazed to think that the viewpoint and the literary oeuvre of Maya Angelou and Virginia Woolf are still so relevant. Kamala Das, Shashi Deshpande, Meryl Streep, Oprah Winfrey are few of my favorites. And I love feminists of all types from Kamla Bhasin, Shobha De, Meghna Pant, Lady Diana, Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, Diksha Bijlani, Kangna Ranuat, Priyanka Chopra, Natasha Badhawar, Shaili Chopra, Aparna Vedapuri, Vinita Agrawal, Joie Bose, Smeetha Bhowmick, Lopa Banerjee, Chitra Desai, Vinita Dawra, Geetika Goyal, Meena Agarwal,Shivangi Maletia, Malala, Emma Watson, Santosh Bakaya, Nabina Das, Neela Kaushik, Joshna Banerjee, Paromita Bardoloi, Abha Singh, Monica Oswal, Shivani Pathak, Smriti Irani, Meena Kandasamy, Milee Aishwarya and all those men who respect and celebrate women. There are many groups, forums and portals which give me inspiration in daily life.

Lopa: What connotations do the coinage of ‘feminism’ bring to your mind as a poet, author, woman and mother?

Feminism is humanism to me, being sensitive and respectful to all humans regardless of gender, race and creed. Feminism to me, is synonymous with equal opportunities, privileges and the status for women at home ground and workplace. Unfortunately, feminism is often seen from a negative perspective, like a feminist is angry, anti-men, rebellious and one who doesn’t conform. But as a poet, writer, mother, feminism to me translates as equality and balance leading to harmony.

Lopa: Keeping in mind that we women have really come a long way from struggling to claim our rightful space in the universe to actually accomplishing giant strides in the diverse spheres of society, has the world really known the importance of gender sensitization?

Meenakshi: The identity of female has gone through evolution in terms of roles and responsibilities. As if earth has boundaries, territory for sexes. Roles were acquired as per the innate qualities of each sex and now is the time where they need to be redefined. We are much beyond the age of hunting where only masculine was revered. In this age of technology, women have all the access, skills and tools to reach out and the professional world needs the gifts of innovation, creativity, communication, which is possessed by both the genders. I feel disturbed to think that in the Indian context, the mindsets of people are still wired, stereotyping the roles of women and men. The Laxman Rekha still gets drawn and the woman who dares to cross it is called a feminazi. Even in the society of animals, there is no gender inequality between sexes but humans hold this distorted view. This gender bias is still evident in the 21st century.

Lopa: Do you think we still need to evolve a lot in our thoughts and actions regarding the true essence of woman empowerment?

Meenakshi: It needs a revolution to shake things and restore that balance and ShetheShakti is not less than a revolution. I would be happy to witness those times when a woman stops imitating a man to prove her equal identity but embraces her womanhood to be able to celebrate herself emotionally, physically and financially. That is woman empowerment to me and that is my mission.

Lopa: The depiction of womanhood, the strength, power, frailty and humanity of a woman in Indian society has mostly been shaped by religious conditioning, by the portrayal of women in mythological epics and scriptures. What is your vision regarding the force of femininity as depicted in religion, culture, literature and epics?

Meenakshi: Indian society is rich and empowered due to its roots but there is no mandate or guideline to renew it to make it suitable to the contemporary times.

I would like to point out the hypocrisy in Indian society, especially in the portrayal of a woman. On one hand, the woman is worshipped in temples as Shakti, the symbol of power and on the other hand, she considered as the weakest, dumbest, lowest creature in the society. I understand the derivation of this philosophy from the financial status quo of a man in the family. But then the woman is supposed to follow certain norms, she is rendered mute and caged in homes. This arrangement of keeping the women confined might have suited in the days where enemies invaded.

But in today’s times, I find it ridiculous and irrelevant. I wonder, unless a woman comes out of her shell, how she would be able to prove her independence, and equalize with a man’s status quo? It is heartening to see so many women coming out, reclaiming their equal rights.

Religion has a significant role to play in a woman’s journey in India. My thoughts could be scandalous but most of the Goddesses, the ideal women were muted, underpowered and followed their counter parts like blind followers. All man Gods had their own vehicles but goddesses didn’t…they sulked and waited and dedicated their lives, waiting for their men. I doubt such mythological depictions. I have my doubts about such stories and fables crafted by men, but then that’s a personal viewpoint. The entire lifecycle is governed by the conditioning a girl child goes through in India. The Indian ethos and norms need urgent revision to suit to contemporary requirements and gender roles.

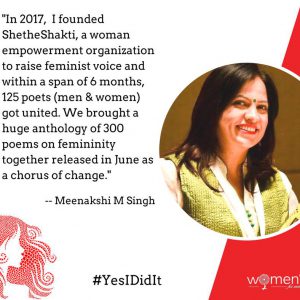

Lopa: Let me also ask you about the organization “She The Shakti Inc” that you founded in 2017, which is an initiative of yours towards attaining woman empowerment. What are the major highlights of this initiative, apart from its literary aspect, i.e., books/anthologies?

Meenakshi: To give back to society, I pledged to have a mission to empower fellow women through their creative expressions and dissent. In order to do this, I launched SheTheShakti Inc., a woman empowerment center, on Jan1st, 2017. It came up with ShetheShakti, an anthology of 124 poets, a grand poetic celebration of feminism, a collective voice towards empowering woman’s voice in the society. It expressed a chorus of change, of celebration, of hope. It is founded to empower a woman’s voice and raise her identity from all aspects. ShetheShakti is also bringing out an anthology of poems, ‘A Chorus of Youth’ by young Indian poets of age 8-16 years, to foster the creative expression in today’s youth as I believe the voices and creativity of youth don’t get platforms other than schools to get unleashed, and ShetheShakti wishes to be an enabler for our future generation. ShetheShakti has tied up with the NGO Neofusion and announced ShetheShakti Star award on Kaka Hathrasi’s Day to recognize the most creative student in neoFusion academy where all under privileged children are getting holistic education under the tutelage of Dr. Anubhooti Bhatnagar.

Lopa: Do you think literature and arts is sufficient to attain the goal of empowering feminist voices, or we need more grassroot level initiatives to attain it?

Meenakshi: Literature and art do possess the power of altering society’s gender consciousness, thereby empowering women. It all sprouts from the mindsets of people; gender equality has to be sown in young minds first so that our daughters can blossom. So literature might not seem enough, but has significant role to germinate gender equality in society. Since ages, history, literature and art has shown the supremacy of men over women and thus we are in this unequal state. If you read any story of a fast which Indian women keep, it’s all about duties and dedication of a woman for men/boys. There is no fast in the Indian culture which is kept for a woman/girl/mother. So the attitude needs to be changed at the grassroots level.

My vision for ShetheShakti is to become an instrument to build such a humane society which celebrates, embraces and empowers girls and women psychologically, emotionally, physically and socially. I am working as a woman empowerment coach at the minimal level now. I am exploring various mediums other than Literature and arts and have high hopes towards ShetheShakti.

Lopa: The best thing I have seen as one of the contributors of ‘She The Shakti’ is the outpouring of the poetic voices of men joining in this collaboration of change. Do you think this will add to its constructive, proactive dissent and solidify the awareness of women being synonymous to Shakti (power)?

Meenakshi: I am grateful that you acknowledged the solidarity and the potency for change in ShetheShakti. Having male poets joining in for feminism and woman empowerment is the most beautiful phenomenon in this endeavor. I salute the male poets, especially for being man enough, for their courage and resonance. As I mentioned earlier, ShetheShakti is all inclusive and stands to raise woman’s voice, but at the same time it carries equal respect for a man’s voice, resulting in a balanced society. You must have noticed that during the recent “MeToo” campaign all around the world, some men also came forward to join in the campaign and it’s beautiful that men also feel it is the need of the times to unmute the silence of women.

Lopa: Creating an anthology is always a collective experience, rather than anything else. However, the cathartic journey of publishing the anthology invariably enriches our sense of self-exploration by reading the literary works of others. Do you think any of the discerning contemporary poetic voices in ‘She the Shakti’ has strengthened your vision of femininity and humanity?

Meenakshi: ShetheShakti stands on behalf of every woman and thus will stay as a collective voice forever towards elevating the status of the half of the world. It belongs to each and every poet of ShetheShakti as it does to me but personally it has been the most fulfilling creative project for me for some beautiful reasons. As I expressed at the book launch program in Delhi that the amount of joy I felt at the launch of Shetheshakti was boundless, way more than I would have felt at my exclusive books. Secondly, I was from IT industry and it was my dream to get published few years back. I knew that feeling of ecstasy and I wanted to give back to the society in a manner to enable others to feel that joy. So we engaged poets in ShetheShakti, including both veteran authors and literary stalwarts and also emerging poets and this concoction is very special to me.

I received so much gratitude and respect to the point of being overwhelmed from contributors from all walks of life, including a scientist, housewife, dancer, doctor, and even an underprivileged woman and an 84-year-old woman. This will stand as my most precious fortune.

I have deep regards for the stalwarts and eminent poets who engaged and graced ShetheShakti anthology and since numbers are huge, it won’t be feasible to list the names here. All the voices bring power, change and uniqueness to build feminine voice and it’s not possible for me to compare and judge anyone’s poetry. Each poet is dear to me and is an important member of ShetheShakti family.

Lopa: As a mother of two daughters, do you wish to sow the seeds of woman empowerment and gender sensitization in their young minds, starting from a tender age?

Meenakshi: I envision ShetheShakti Inc as a change maker in the society towards an equal, humanistic, sensitive and egalitarian world.

Me and my husband used to work together. I chose to quit my corporate job when my twin daughters were born. I did receive consolation from a few aged neighbors for giving birth to twin daughters in this 21st century.

My role as a nurturer at home has never been looked down upon and I am able to pursue my passion of writing as my choice. So the seeds are already sown in the psyche of my daughters. And the way we celebrate the presence of our daughters does bring delight to my heart and a sign that times have changed. My writing, my choices and my identity must have played a role in shaping the viewpoint of my daughters about a mother.

My twin daughters Mihikaa and Maansi are stronger feminists than me as I have encountered during our discussions. Once there was a placard, “Save the Girl child” when my daughters were just 5 years old. Then Maansi had asked: why not save the boy child, mama? At home, sometimes we pass statements like girls keep their room clean due to our conditioned minds and instantly my daughters correct us pointing out the gender stereotype and then we need to utter the correct statement: kids keep their rooms clean. I wish in our future generation, both sexes are always treated equally.

I feel delighted when my daughters look up to me and want to be like me when they grow up. It reflects they have no such prejudices that a woman needs to be submissive and apologetic about her choices.

When we were children, it wasn’t easy for our mothers to make independent choices and they would have felt apologetic if they partied or dressed up like today’s women do. They were apologetic for claiming their own freedom. I could claim that my pen gave me that power and confidence.

Once my daughter asked me that why do we worship these goddesses and who’s the best? There is a poem of mine, “Don’t be a goddess dear daughter” which I wrote, reflecting on a role model among our Indian goddesses. I told my daughter to be her own goddess than follow anyone though my daughters are not that old to understand the meaning fully. I was quite apprehensive to recite this poem in public as it could indicate sign of blasphemy, but as a poet I felt it was my responsibility to show the mirror of our society and to discard irrelevant thoughts. This poem has been well received in all forums and I believe the society is ready for change.

Lopa: What are your future endeavors towards women empowerment, empowerment of the girl child and societal changes?

Meenakshi: I envision great things for ShetheShakti, but since I chose to raise myself through raising my daughters and being there physically present with them at home, I am working from home. I envision expanding this center to be an institution of creative expression, running workshops, open mics, theatrical workshops, bustling with creativity, art and nurturing women empowerment, thereby transforming our society into a sensitive and humane one. It will be an organization where women come to realize their innate potential. I founded this single-handedly and would be happy to have like-minded partners and a team towards strengthening ShetheShakti.

Woman empowerment doesn’t translate into aping men or being like men but being like a woman, embracing and celebrating herself, as is. In this consumerist age, women need to go beyond pink and be truly empowered beyond the stereotypes of looking good. Rather they need to feel good from within. And when one woman stands to empower another woman, the results are better as it is the women who have a bigger role in society to weave its mindset. So it’s time that she doesn’t feel limited, confined and prejudiced.

We envision a transformed world where both the sexes collaborate in tandem as Shiva & Shakti. That is our legacy for our sons & daughters to blossom in a gender-neutral society. She is the Shakti herself and she needs to realize and believe in herself that she is enough, as is, always.

Lopa Banerjee is an author, poet and editor based in Dallas, TX. Her memoir ‘Thwarted Escape: An Immigrant’s Wayward Journey’ and her debut poetry collection ‘Let The Night Sing’ have received honorary mentions at Los Angeles Book Festival 2017 and New England Book Festival 2017 respectively. She has also received the International Reuel Prize for Poetry (2017) and for translation (2016), instituted by The Significant League.

Meenakshi M. Singh is an author, founder of SheTheShakti Inc., a woman empowerment centre. An author of three books, her literary work has also been published in more than 50 national and international anthologies and journals. She has been conferred the much reputed Karamveer Chakra Award, the REX Global Fellowship and also the Magicka Women’s Achievement Award, Pride of Women Award by the Agaman group and the SashaktiNari Parishad Pride of Nation Award in 2015.