Nanowrimo Advice on Failure from Minal Hajratwala

Jaggery’s own Ask the Unicorn columnist, Minal Hajratwala, gives advice on National Novel Writing Month (nanowrimo):

FAILURE

Dearest lovely writer,

Halfway through, it’s about time we start thinking about failure.

I’ve already written ##,000 words. I’m out of ideas, my fingers hurt, and my dog misses me. Plus it’s the holidays. Maybe I should quit while I’m ahead.

I’ve barely written #00 words. I’m a zero, basically. I’ll never catch up now. Why bother? I’m going to the NaNo FAQs to see if I can take my profile down.

What do we do when faced with the great gaping jaws of failure?

I often wish I could be one of those cool-headed, even-keeled writers who pumps out a steady stream of prose during the 9-to-5 hours and then gets to go out for beer and biryani.

Maybe you’re one of them. If so, congrats to you! I don’t hate you. No, really I don’t. A little envy, maybe. What, I look green? That’s just because one of my characters has been ingesting Paris Green.

The truth is, I’m not that kind of writer. Never have been. I despise the 9-to-5. I sleep through most mornings. My favorite writing time zone is 1am to 3am. I don’t drink beer.

And the more I remember these things about myself, instead of sulking and envying, the more writing I get done.

What about you? What kind of writer are you? As you pump (crawl?ooze?) your way through NaNoWriMo, don’t forget to notice what you’re learning about yourself and your writing.

What are your inner critical voices saying, and how are you getting past them — or not?

What time of day works best for you? What boosts or saps your energy? When do you love writing? When do you resent the heck out of it?

What do you do when you think you “should be” writing? What habits have you developed to avoid your writing? How can you defeat your own self-defeating habits?

These questions, and what you notice about your writing, will serve you long after November 30, whether you meet your goal or not.

By this point in my writing life, I know my habits pretty well. When I’m not writing, I’m often checking my email or Facebook. As a working writer and writing coach who is gearing up for a book tour, I actually have legitimate reasons for being online. (You probably do, too).

The other morning, for example, instead of writing, I replied to an interview request from the BBC, updated my website events page, publicized an upcoming workshop by posting it to some Facebook groups, scheduled a coaching call with a client, and went online to order a new bookshelf for my writing room to take advantage of a 25% discount — all valiant, justifiable uses of my time.

And yet… the whole time, I knew I was avoiding my NaNo novel. I’d write an email and think, “I should do this later and write now.” I’d pen some scintillating marketing prose and think, “I should be writing my novel now, not this.” After all, it wasn’t as though I had no free time at all; I also cuddled the dog, took a long nap, and played a video game.

And then, eventually, after all that, niggled by the nagging feeling (or nagged by the niggling feeling) that I was behind schedule, and haunted by the (again legitimate, justifiable!) lack of writing for the previous two days … I wrote.

I got over the voice saying “failure, failing, fail” by admitting that, yes, it’s true. I might completely, utterly fail.

At my novel. At my life.

I actually only have 19 writing days available in November, so my goal has been to write 2,632 words per day. Whew! So far, I’ve mostly failed. I’ve met that daily target only once.

But I’m writing. I’ve written on days I thought I wouldn’t be able to; I’ve surprised myself with both my devotion as well as my apparently not-yet-tapped capacity for procrastination. My novel is growing, and I’m understanding the characters better. I haven’t lost the plot; hey, look, I even have subplots!

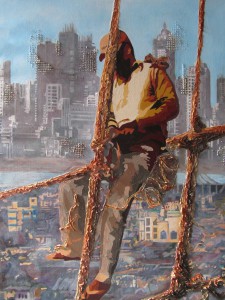

Your mileage and methods may vary. When I met our fantastic India ML for a quick co-writing session in Mumbai, she noticed that I write longhand. Yes, I’m old school. Eventually I move onto the computer, but I write in notebooks.

How do you count? she asked. I use an average words-per-line, roughly approximating each page as I go.

When I’m stuck, I write directly about the process of being stuck. It usually helps me figure something out and get moving. This counts; this is work on my novel.

I’ve also made a four-pages-and-growing list of freewrite topics, so that I can just grab one and go in each writing session — one of the strategies I suggest for my writing students and clients. Don’t have a topic list? Make one (yes, that list of words counts toward your total!), or follow the NaNo sprints on Twitter, or just email me and I’ll send you my 10-Minute Writing For Muscles of Steel exercises. It’s all good. There’s no wrong way to do this.

Write on your own personal timezone. Write blindly, not even looking at what you’re typing. Write long nasty letters to your own inner critics. But write.

And if your inner editor is whispering lots of sweet-nothings about failure, join me in the goal I’ve set for this month: to become the most verbose, wordy, prolific failure in the history of literature.

I’ll race you there.

Love,

Minal