Sofa Talk

by Anu Taranath

My two kids and I relax on the sofa watching Bollywood film songs. The laptop sits balanced on a pillow on my knees, and we screen one heart-pumping colorful video after another. My five-year-old daughter snuggles with me to my right, my two-year-old son on my left. Many of the tunes are familiar to us. On most days, Hindi film songs blast loudly while we get ready for school or wind the day down in the evenings. Sometimes, when the music is particularly catchy one of us will yell, “Dance Party!” and we stop what we are doing and dance together in a row.

While we listen to Bollywood songs often, I don’t let the kids watch many Bollywood videos. Garish, lavish, and some would say lewd, the videos of some of the best throbbing songs often feature gyrating ladies dressed in small and tight fare. These “item numbers,” as they are called, make big money for movie producers, and serve as a crucial magnet for publicity and revenues. Some are set in a Westernized nightclub and some at a South Asian mujra (a dance performance with roots in the Mughul era). Regardless of the setting, characters, or plot, the cameras focus on lady parts and lady skin. Today, the kids are fascinatedly watching the screen. I feel protective, and fast-forward the too-sexy parts.

My daughter suddenly points to the screen. “Ammi, this is an Indian movie, right?”

“Yes. Indian movies like this are called Bollywood movies.”

“See that Bollywood main lady dancing in the middle of the group?” Her finger follows the actress on the laptop screen. “If she is Indian, why is she white?” Her little brow is scrunched up. She continues, “How come all the dancers around her are white if this is an Indian movie, Ammi? Indians aren’t white, we are brown! How come only the boy actor is brown and all the girls are white?” She continues to point, and pants from the exertion of her thoughts. She pivots her gaze away from the laptop toward me. Expectant, she waits patiently for my answers. Her brother pipes up and repeats in baby-talk a few of his sister’s words, “India movie oovie.”

What my daughter has noticed is indeed true: the director has cast all the backup dancers as white (and waifish), and the costume director has outfitted them (barely) in sequined bras and veils. This is a larger trend. In the last decade or so, women from Russia, Ukraine and other Eastern European countries increasingly feature as backup dancers who flank the heroine or hero. Casting skinny white women as backup bestows clout, panache, international credibility and foreign style. Some of the Russian and Eastern European women might indeed be excellent dancers, but the decision to cast them in Indian movies ultimately reflects the symbolic and preferred nature of whiteness. Mainstream Indian cinema also prefers its Indian actresses light-skinned and thin, reflecting a culture-wide obsession with fairness. In the song that the kids and I watch, the heroine belongs to a famous filmi family and is known for her fair skin tone. “Oh, what color she has!” audiences gush, which actually means, “Oh! How great that she is not dark-skinned.” The actress suggestively thrusts her sequined hips and breasts in time to the music while her male, dark-skinned, on-screen love interest ogles her wiggling body.

My daughter taps my arm, reminding me she’s asked a question. Asking questions comes naturally to kids. My daughter, like most young people, hasn’t yet learned to censor her thoughts about what she notices, and she hasn’t yet learned not say certain things because it might make someone uncomfortable. So she asks the big questions easily, with an ease I have only recently cultivated as an adult. “You’re right,” I tell her. “The main actress is Indian, but her skin color is very light brown. She’s more tan than brown, actually, well, really light-colored tan.” I get a bit confused over how to convey light skin on an Indian as distinct from light skin on a white person, even if the two shades are similar. I continue, “All the other dancers around her are actually white ladies. They are not from India. These dancers come to India from Russia and Europe to dance in the Bollywood songs.”

“Why do they bring ladies from Russia and Europe to dance, Ammi?” she asks. “Couldn’t they find any brown Indian ladies to dance in the movies?” She is so earnest, and it is such a hysterically naïve premise—that the lack of “brown ladies” who can dance in the world’s second most populous nation has forced movie directors to exclusively cast Russian and European white women—that l laugh uproariously. The kids delight in the joyousness, even though they don’t understand what I’ve found so funny. We play together for a few minutes before I plunk each of them beside me.

“Do you know why so many white and light-skinned people are in that movie?” I ask the kids. They stop squirming and listen. “There are lots of different skin colors in the world, right? Light-skinned, white skin, tan, light, medium and dark brown, light, medium, dark black—all different kinds of skin color, right?” The kids nod, and look down at their arms to appraise their own color. “I know you love your brown skin,” I say, “but can you believe that some people think that white skin is more beautiful than dark brown or black skin?”

The kids audibly gasp, even the small kid. Their eyes puff like toads with amazement. I love the theatricality of this conversation. “That is why we see many light-skinned people on TV, in movies, cartoons, magazines, and as characters in books. Most of the people who have been in movies and TV have been white and light-skinned, so people aren’t used to seeing dark-skinned people. But what do you think? Do you think brown and dark-skinned people can be on TV?”

They watch me intensely, not sure how to respond, so I exaggerate a nod. “Yes!” they answer, taking my cue with a big nod themselves.

“Can dark-skinned brown and black people also be in movies? Or cartoons? Or in books? Do you think so?” I prod.

“Yes!” they chime again, thrilled with themselves and this game.

OK, we’re on a roll here. But then I’m flummoxed all over again, for even though the Bollywood movie industry explicitly reproduces white/fair/light-skin privilege by casting light-skinned Indians and white people, I don’t want to give the impression that white/fair/light-skinned people are somehow themselves suspect. A healthy critique of white privilege and whiteness is not the same as disliking white people. Can kids understand all this, I wonder, all the nuance and subtlety of race? Additionally, South Asians actually come in a variety of skin tones and appearances; we do not have one particular phenotype or look only one way. I don’t want to inadvertently give the impression that darker-skinned South Asians are somehow more authentic. The privileges of being light-skinned, however, are real, both on the subcontinent and in the diaspora. How do I convey all this to five- and two-year-olds? I myself am not sure how to simultaneously celebrate the amazing heterogeneity of people’s features, skin tones and appearances while also remaining vigilant against the pernicious effects of whiteness that seem to saturate media.

“You know,” I start off, “brown people are all kinds of brown: light, medium and dark brown. We are so many different colors of brown. Shall we play a game?” I ask, and they get all excited again, scrambling on top of me. “What color is Ammi?” I ask, and they both grab at my arms to see.

“You are dark brown all over!” my daughter shouts.

“What about Pappa?”

“Light brown!”

“Abhi Mama?”

“Dark brown!”

“Ajji?”

“Light brown!”

“Dr. Shazia?”

“Light brown!”

“Anju Akka?”

“Dark brown!”

“Bhanaa Chikki?”

“Medium brown!”

“Nafisa Aunty?”

“Very light brown, maybe white…?” My daughter’s voice trails off a bit, for she’s not sure of her response.

We pause and I say, “Nafisa Aunty’s skin color might be like that actress’ skin color, very light-skinned. But is Nafisa Aunty still Indian?”

“Yes, of course!” she agrees.

“But I thought we had to have medium or dark brown skin like most of the Indian and Pakistani people we know,” I prompt. I feign an exaggerated confused look. “What do you think, kiddie?”

“No, no,” my daughter shakes her head. Her brother too mimics his sister and shakes his head, his long hair flinging this way and that. She tells him to stop (which he doesn’t), and takes a deep breath. “Ammi, I know, I know! Indians and Pakistanis and Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis come in many brown colors. Light, medium, AND dark. But everyone still is Indian or Pakistani or Sri Lankan or Bangladeshi.” She looks up at me, eyes bright, a bit precocious, wondering if her thesis is correct.

“Yes, baby!” I praise, kissing her cheek. A month ago she saw me reading The Other Side of Silence, Urvashi Butalia’s book about the 1947 Partition into India and Pakistan. “You mean people can break countries into two?” she had asked then when I explained what I was reading, incredulous at human power. We had looked at the South Asian map together, and I had told her how Indians, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis now had their own countries, but still shared many cultural similarities.

My daughter tugs on my necklace and pulls me back into the present. “All varieties of brown can be included in us,” she says. Her funnily-put-together sentence makes me smile. I gently take the necklace out of her hands and laugh, “Yes, all varieties of brown are included in us, kiddie.”

Suddenly, her eyes cloud over, concerned. “But Ammi,” my daughter asks, hands pressed up against my face, brows once again worried. “It just isn’t fair that the main ladies in the Bollywood movies are so much light brown! What about all the dark brown girls like you? What about all the medium brown girls like me? Don’t they want us in their movies? See? I can dance too!” she emphatically states as she twirls around.

Do I tell her that yes, she’s right, dark brown or even medium brown girls might not be a director’s first choice for their movie? Or do I lie to build her confidence and say, “Don’t worry, baby. You too can be in the movies! There is place for dark brown and medium brown girls just like us!” I certainly don’t want my daughter to dream of Bollywood, Hollywood, or any -wood that will attire her future bosom in sparkly sequins solely for the lascivious male gaze. But I also don’t want to dissuade her from the dance of dreaming itself.

When do we tell our children of color the racial legacy into which they are born, or our girl children about patriarchy’s reach? How do we keep our children and communities safe, but not squash their sense of what is possible for themselves? The racial politics of Bollywood casting measure small compared to what other communities of color in the US, for example, must deal with, including police profiling, institutional bias and the seemingly routine disregard for black life. These dire concerns are literally about life and death, and are part of the same machinery that privileges one type of people over others. Doctor, activist and writer Paul Farmer has said, “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.” He’s right. From the racial politics of movie casting to everyday police profiling, the sexualization of women’s bodies to the power to break countries into two: all these instances tell the story of some group that is more powerful than another. These bigger stories then merge with and shape our own smaller stories. When our kids go out in the world, they will hear and see and experience a range of unfairness. If we give our kids the framework, language and tools to wonder why people like us aren’t on our screens or why some lives matter less than others, perhaps they will dance with rhythms of justice guiding their feet and songs of truth in their hearts. You or I can’t upend the bigger story of unfair power, but in small ways we can bravely name what’s actually happening.

![]()

Dr. Anu Taranath is a speaker, facilitator, and educator. She teaches at the University of Washington about global literatures, identity, race and equity. She’s been part of Humanities Washington Speaker Bureau, received Seattle Weekly’s “Best of Seattle” designation and the UW Distinguished Teaching Award. As a consultant, she engages with students, faculty, K-12 teachers, and government agency employees to deepen social justice, equity and global consciousness. She’s finishing a book on identity, social justice and global travel.? For more, please see?www.anutaranath.com.

Dr. Anu Taranath is a speaker, facilitator, and educator. She teaches at the University of Washington about global literatures, identity, race and equity. She’s been part of Humanities Washington Speaker Bureau, received Seattle Weekly’s “Best of Seattle” designation and the UW Distinguished Teaching Award. As a consultant, she engages with students, faculty, K-12 teachers, and government agency employees to deepen social justice, equity and global consciousness. She’s finishing a book on identity, social justice and global travel.? For more, please see?www.anutaranath.com.

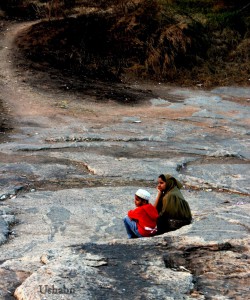

Image Credit: Quinn Brown.

Thank you for this accessible and terrifically visual article on how to use small moments with your children as teachable moments!

So many beautiful moments in this piece! I loved this observation in particular:

“A healthy critique of white privilege and whiteness is not the same as disliking white people.”