Roots, Music

by Sunil Freeman

I remember a bird gliding over the Potomac River, then soaring above the lush foliage of Roosevelt Island, an almost musical arc to the dip and rise of wings caught in shifting moments of light. It was early evening; sunlight spilled a soft wash of gold over the city, casting sharp accents over the distant spires at Georgetown University and National Cathedral. There must have been a boat or two drifting down the river. I wish there was music onboard, and that it reached us on the shore. Classic Motown somehow seems right. It was 1982, give or take a year.

I was on the lower terrace at the Kennedy Center, waiting for a concert by Bismillah Khan. I’d never heard of him but was immediately drawn because a recent article in the Washington Post had noted his influence on John Coltrane. Coltrane. Trane. How to begin to explain John Coltrane’s impact on me.

I had grown up with the sounds of classical music: Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, and others. The soundtrack of childhood included both my sisters playing Schubert’s impromptus on the piano at home. But even more than Schubert, there was a composer my father loved, Charles Ives. Ives’ music had a wildly anarchic quality, seeming at times to be a celebration of the right to play “wrong” notes. My sisters, mother and I thought of it, affectionately, as “Daddy’s crazy music”. Over time I came to love it.

I was also surrounded by other music my parents enjoyed, including records by master musicians such as Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar. Though I enjoyed it, I didn’t know much about it, and still can’t differentiate between a “morning” raga and an “evening” one. Although we had no jazz or rock at home, I’m fairly certain our musically rich home nurtured the openness and curiosity that led me to John Coltrane.

* * *

It started in the Silver Spring and Wheaton, Maryland, public libraries. Picture a suburban kid, about fourteen, bored with school, who in his undisciplined but wide-ranging readings began to come across the name “John Coltrane.” I learned that Coltrane played tenor sax with Miles Davis before forming his own groups. Though I’d never actually heard any music by Coltrane, I sensed that the critics’ prose was often elevated, reaching toward something transcendent, when they wrote about him. It was as if some greatness, or at least some aspiration toward greatness, rubbed off onto people who focused their attention on him.

After having read all I could find about Coltrane, I borrowed a library record, Live at the Village Vanguard (Impluse! Records; 1962) turned on the stereo and placed the tone arm down on the title that most drew my attention – Spiritual. A yearning saxophone cried out, ecstatic and yet filled with grief; it sang in a minor key above a dark landscape sculpted by piano, bass, and drums. Below it, Eric Dolphy’s bass clarinet pulsed, mining a vein of sorrow deeper than any I had ever known.

* * *

I didn’t know there was so much emotion in the world, or that it was all in my heart. Years later, trying to describe that moment, I told a friend that my life grew exponentially in those first few seconds I heard John Coltrane. I would not have used a word like “exponential” that instant when the music blossomed out of the grooves and took hold of me, but I knew that my life had changed forever.

My brief moment of wonder came to a sudden halt when the theme ended and the ensemble began to improvise. It might as well have come from another universe; it was incomprehensible. Baffled, I tried again and again to make sense of it but finally gave up, and just played the theme over and over as if it were a 45 rpm single. I’d let the gorgeous, painful music wash over me, then rescue the stylus when the strange noises began. It was like reaching the edge of a neighborhood and turning back. Even then I sensed the flaw wasn’t in the music.

I should note, in hindsight, that today Live at the Village Vanguard is easily accessible. Coltrane was often ahead of his time, and critics, disturbed by long solos in which he and Dolphy stretched beyond usual harmonic, rhythmic, and tonal boundaries, vehemently denounced them for playing “anti-jazz.”. Years later, when people came to appreciate their adventurous musical explorations, they were well accepted. You might even say Live at the Village Vanguard has become a part of the canon. I was a child unfamiliar with jazz, hearing it closely for the first time; Spiritual was a roller coaster I just wasn’t ready to ride.

A year later that same music, and Coltrane’s last avant-garde albums, made perfect sense. The sounds fit my ears, my body, my heart. My parents grew used to the music of Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Charles Mingus, Miles, Dolphy, and others. Sometimes, as his soprano sax blew through the house – usually “My Favorite Things” or “India” – my mother, who is Indian, said that he sounded “just like a snake charmer”. I was too enamored of the music to realize that she might not be paying a compliment.

* * *

A dozen or so years later I stood on the terrace of the Kennedy Center, taking in the evening before Bismillah Khan’s concert. A dove soared over the river; perhaps Aretha Franklin and Marvin Gaye tunes drifted up from a party boat. I had about a half hour to be quiet, to tune myself to hear the music.

Bismillah Khan played the shehnai, an instrument somewhat similar to an oboe, not too far from the sound of a soprano sax. Long associated with musical ensembles in north Indian temples, shrines and courts, the shehnai only became prominent in serious Indian classical music when he began to play it with such technical prowess that he redefined its possibilities. He could be to shehnai what Segovia was to the classical guitar.

Half-Indian, I entered a concert hall full of Indians. When I shop in Indian stores the proprietors look at me aslant, with an expression akin to a bent note in the blues. I imagine them thinking, “there must be a story in here,” as I wander through aisles of incense and chutneys, looking as if I have a big thought on the tip of my tongue, turning slowly, like a confused dancer, to scents of cumin and coriander.

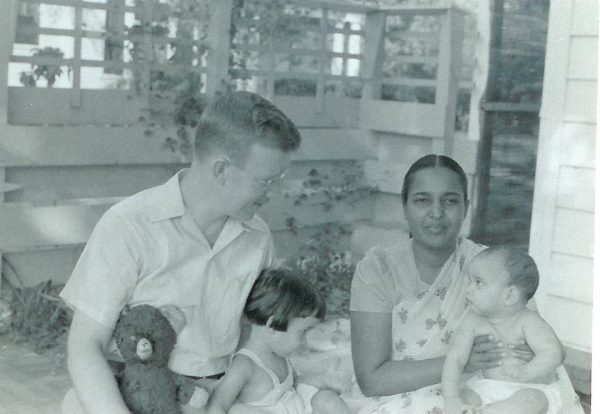

My father, son of a progressive North Carolinian Baptist preacher, was in India with the Quakers’ American Friends Service Committee in the late 1940s, a time of great upheaval as Britain relinquished control of its former colony. “Progressive,” in the first part of the 20th century meant my grandparents held interracial Bible study groups in their Raleigh home in the 1940s, and took in a young, ethnically Japanese Baptist minister who would have otherwise been sent to the Nisei internment camps during World War II.

My father became a Quaker in his teens. Though he and my sisters had all marched in demonstrations against the Vietnam war, it wasn’t until years later that he told me that some of the best people he’d ever known were communists who also fought against racial injustice in the south, recalling his experiences as a counselor at Quaker summer camps in the deep south in his teens.

He’d hitchhike from his home in Raleigh, sleeping in a field and continuing the next day. Black and white children met and played together as equals in these summer camps. This would have been in the late 1930s. When I asked if people in the local communities knew about these integrated camps, he just said that a few in the Black community did, but the others didn’t.

My parents met in a large refugee camp at Kurukshetra, the site of the battle described in the Bhagavad Gita. My mother was a volunteer working in a pre-school program for young children and teaching a Hindi language class for adults. My father began to attend her class. There on the ground where a millennia earlier Krishna instructed Arjuna, he proposed. She declined for three years, then changed her mind. My sisters and I were “conceived,” in a conceptual, not biological, sense, in a language class.

* * *

Memories of India, the heritage I’ve never denied, but never fully claimed, returned as I waited for the music to begin. A few years before my first encounter with Coltrane, I had another shatteringly powerful experience. My mother, father, sisters and I were in the Bombay (now Mumbai) airport, having just landed in India. I was almost ten years old; we would spend most of 1965 in New Delhi.

Until that day, I had thought of myself as an American child with an American father, and an Indian mother who wore saris, cooked delicious Indian food, and considered cumin an essential ingredient when making hamburgers.

I was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, but we moved after a year when my father received a Fulbright scholarship to teach in India. We were there for two years, then returned to the U.S., so I absorbed the country with wide-eyed wonder but retained no conscious memory of it.

That afternoon in Bombay, waiting for friends to meet us at the airport, I was back in the land before memory. Too young to conceptualize or understand the idea of deja vu, I sat, immersed in a joy that carried me through that entire year. In my heart, in my bones, I was home.

* * *

I remember looking across a river through a latticework of cut marble to the Taj Mahal. The day had been one long, slow crescendo of anticipation. We left the palace and its dark history – a plotting relative blinded to prevent further mischief, jewels stolen by the British Raj – and headed toward the Taj Mahal.

We crossed a huge archway to the grounds, lush greens, pools of water, and then we were on the marble structure itself. I did the only thing possible in the face of such emotion: I ran, seeking exhaustion, on the broad marble of the Taj Mahal.

We returned that night and joined hundreds of people who had gathered to sit before this gorgeous white marble. The peace was overwhelming. Years later I looked back and saw that night as something like the communal energy high at Grateful Dead concerts I’d seen at RFK Stadium, but instead of music, the seed giving birth to the whole wondrous occasion was silence, a dream of love manifested in white marble bathed in moonlight.

* * *

That summer we vacationed in the hill town of Sattal. “Sat” means seven – think the Spanish siete, the French sept – and “tal” means lake. The town was nestled in a region with seven small lakes. As we drove north from the plains, I saw clouds on the distant horizon, and then those shapes began to enlarge, drafting and etching their way, part sight, part imagination, toward the land. The clouds, I began to realize, were our destination. Heaven and earth were one; soon we were climbing winding roads into the sky.

Sattal had just a few cottages scattered on the hills, with the seven promised lakes. At that time of year tiny tree toads were everywhere, an almost magical presence about the size of a fingernail. There were three hills, each with orchids just to the side of our cabin. The pine forest was carpeted with needles, and the fragrance filled the air.

We took winding bus rides twice to visit family friends at Nainital and Ranikhet, much larger towns at higher elevations. I dreamed of seeing snowcapped mountains. My best hope was Ranikhet. We stayed two or three days, but the sky didn’t clear enough to see the high Himalayas. The day after we left, those peaks I’ve dreamt of, and drew obsessively as a child, were visible.

* * *

We lived in New Delhi in a house near a large field that sometimes was home for cricket games. An ancient tomb, apparently from the 13th century, was on one side. An abandoned temple stood on top of a rocky hill nearby. One evening, my younger sister and I climbed the hill to the temple. Looking into the distance, the temple rising to my left, I suddenly flickered into a trance-like sense of eternity. I still don’t know what happened, but will never forget that moment.

We often took long walks. One morning, reaching a path not far from our house, we suddenly entered ancient, rural India, fields a brilliant sun-dazzled green, so vivid the color hit like a thump in my heart. It was perhaps the most powerful experience of color I have ever known. (The only other such moment, almost as powerful as an electric shock, had occurred a few years earlier: My first sight of the field at a Washington Senators baseball game with my father.)

We returned to America at the end of 1965. A decade later, reading Rabindranath Tagore’s prose poems in Gitanjali, the India I had known – the temple on the hill, twilight scenes on the edge of the city, the train journeys, the mountain air awash in the scent of pines, the vibrant green of rural fields – came alive in poem after poem. In Tagore’s words I learned once more how India is a part of me, always present beneath the surface of my American life.

* * *

An ensemble of musicians walked onstage, sat on the floor and began a slow, droning theme. I had expected to be transported immediately, but the music meandered aimlessly; it was boring. The rest of the audience was fully engaged, transfixed.

I decided not to even try to like it, dropped all preconceptions, and slouched into my seat. After several minutes Bismillah Khan’s melodic line became a thread, which turned, pulled, and suddenly, effortlessly, I was bought into the music. Shifting nuances and tonal colors revealed themselves as the thread merged with the droning, pulsing harmonies. I was breathing more slowly, leaning into the music. It was stunningly beautiful.

The audience and musicians came together to create a larger whole. It was not as loud an appreciation an audience might give listening to a great jazz or blues band. The music washed over us in a pulse, with a wave-like quality. We fell in tune with the rhythms of the drones, the melodies weaving through them. I could hear a collective breath that was just on the edge of a sigh occasionally eliciting a soft exclamation after a particularly fine phrase. These impromptu vocalizations, never excessive, were like whitecaps curling over the lip of a wave.

I lost myself into the music, into the crowd. After a while I started to wonder how the theme, which seemed so pointless the first go-round, would sound when it returned at the close of the piece.

That thought immediately took me back to a school field trip to a planetarium in Rock Creek Park. I was about eight years old, arrogant with the smugness of a child who knows he is smart. We’d been told, before the show began, that the ceiling would begin to look like the sky. I glanced skeptically at the rounded blue overhead. It would always be a ceiling – how could people be so stupid as to think it looked like the sky?

The theater darkened, stars came out, and a rapt room full of students received a tour of the universe. When the lights slowly returned I stared up into that sky blue, awestruck, unable to make it return to the man-made ceiling it had been moments earlier. It was a humbling that felt good, as if the universe was telling me there were still surprises in life, that I still had a lot to learn.

The ensemble roared into the theme with a muscular, ecstatic force that must have thrilled an American musician named Coltrane so many years ago. Coltrane. When the music ended I let the sound of his name roll around a bit. Coal Train. Those two words danced in my head. Energy and motion; deep stuff of the earth that fueled the course of history. Then, half hypnotized in the dreamy buzz of Indian languages all around me, languages I’ll never understand, I headed on out into the night.

![]()

Sunil Freeman’s essays have appeared in The Delmarva Review, Gargoyle, Washingtonian, and other publications. His poems have been published in several journals and anthologies, including Delaware Poetry Review, Minimus, Sulphur River Literary Review, and Kiss the Sky: Fiction and Poetry Starring Jimi Hendrix. He is author of one poetry collection, That Would Explain the Violinist, and a chapbook, Surreal Freedom Blues. He has lived most of his life in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area.

Sunil Freeman’s essays have appeared in The Delmarva Review, Gargoyle, Washingtonian, and other publications. His poems have been published in several journals and anthologies, including Delaware Poetry Review, Minimus, Sulphur River Literary Review, and Kiss the Sky: Fiction and Poetry Starring Jimi Hendrix. He is author of one poetry collection, That Would Explain the Violinist, and a chapbook, Surreal Freedom Blues. He has lived most of his life in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area.