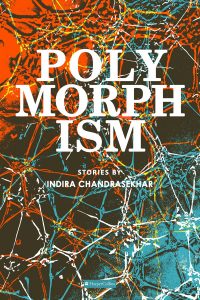

Polymorphism by Indira Chandrasekhar

Reviewed by Shikhandin

Indira Chandrashekhar’s debut book Polymorphism casts a net of stories in which her narratives slip through like eels among the reeds of reality, keeping her readers in swift pursuit. Her stories are either set in alternative worlds or are alternative worlds in themselves. Built around either familiar surroundings or strange settings that curiously resonate with familiar emotions, the stories catch her readers unawares. The real and the surreal merge deftly, making it nearly impossible to sieve the two elements. This is perhaps the book’s greatest strength.

‘Polymorphism’, the title story, for instance, appears to be a cameo of maternal instincts and filial ties. A woman’s handbag is snatched on a road. She seems to be in need of medication and returns home to children who come across as normal, concerned teenagers dealing with a sick mom who may also be a bit of an ‘embarrassment’. But, there is a “viciously sharp chord” lying in wait to jolt the reader.

The second story, ‘Intensive Care’, swings like a double edged sword. Sarasa, the protagonist, suffers from an illness that has made her increasingly frail. Her adoptive daughter feels her helplessness so intensely that she wants to match her own breathing with Sarasa’s. Rajiv, Sarasa’s lover, is brusque in contrast, more cruel than caring. Taut and intense, this story vibrates with strange emotions; not all of them benign.

In ‘Adoration,’ a man’s lifelong obsession with a movie star culminates in his entry into her home, thanks to his childhood friend Salim. But the layers start to peel away the closer he gets to the sanctum sanctorum. ‘Be careful of what you wish for’ seems to be the unspoken catchword here. And yet, heaven does lie at the dream’s end.

In ‘Black Sari’ five lower caste girls live as tenants of a young upper caste widow in the front hall of her spacious home. There is another woman as well whose relationship with the house-owner isn’t clear. Chandrasekhar builds a complex narrative of boundaries and spaces and what freedom means to all the characters including, finally, the narrator. Like ‘Black Sari,’ other stories in Polymorphism also record the fragilities of rigid societies creating situations where their protagonists try to cope and survive. Some like ‘She Can Sing,’ ‘Any day Now’ and ‘My Kitchen My Space’ are straightforward narratives of emotional struggle. Others like ‘The Perfect Shot,’ which recounts the lives of a model and her photographer lover in a fascist society and ‘The Shift,’ which depicts a couple in love with water and its shifting colours as the leitmotif, seem a bit weaker in comparison.

Chandrasekhar skilfully creates deft shifts in pace, sometimes deliberately pausing midway, as if urging her readers to take a deep breath before plunging right back in to the narrative. Her stories are studded with tactile imageries condensed into pacey sentences. Sample this, “Mala’s lungs emptied as if a sudden pre-monsoon pressure change had thrust itself densely into her diaphragm” (‘My Kitchen My Space’). Or this, “Her heels, however, made distinct pear-shaped marks on the floor, as if they were shallow energy wells rooting her temporarily to the ground” (‘Leonard-Jones Potential’ – a tender story through which wafts a scent of loss. It blends science and emotions in a literary petri-dish). Or this one, “The fine network was alive and dynamic, joining, moving – clotted pathways of fluid carmine blood” (‘We Read the News,’ where Chandrasekhar walks us through a terrorist attack with remarkable cinematic effect).

‘The Insert,’ one of the most powerful stories in the collection, is about a dystopian suburbia where land is actually inserted into a cityscape, thereby literally conjuring up more living space. There, families are separated and re-assigned. ‘Abandoned Rooms,’ another dystopian narrative, is evocative of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. The story is set in an unnamed city (like most of Chandrasekhar’s tales) that possesses human breeding factories. It is narrated from the point of view of a human reject or a product of a failed breeding experiment who wants to have her own child. It’s a sensitive portrayal of the city’s detritus, of people who must live between the spaces due to their humble station in life.

In contrast, ‘When the Children Come Home’ is a piece in realism that can easily slip into the sub-genre of horror, a social horror. The situation and setting is eerily reminiscent of an Indian family’s traumatic experience in a Nordic country whose authorities either didn’t or simply refused to comprehend the cultural differences in/and child rearing practices. In Chandrasekhar’s re-imagining, the two children are taken away, and no explanation is offered. The mother loses her sanity. The children are returned eventually but the family is scarred forever; the daughter becomes a foreigner, almost. The key word here being almost – standing in for hope.

‘Does the Word Even Exist in Our language’ is another complex story and it’s about exploring one’s roots. It is narrated by a boy who interacts with and observes a group of (presumably) NRI students on a study break to discover Indian village life. But dig deeper, and it’s all about perspective, which side of the fence you are standing in. And should you just let sleeping dogs lie? ‘Rock Fall’ is that classic tale with a twist like a Hitchcock movie. Rugged terrain, blazing sun, boulders that glisten black, a quietly efficient tour guide, a tourist passionate about the place’s history and a little dramatic re-enactment. Chandrasekhar never lets go of the pace, never lets on what’s waiting round the corner of the steep path or down in the crevice. The end is a cliff-hanger except that there is no resolving chapter afterwards. A disturbing image, dark and quiet lingers in the reader’s mind. This image makes the tale a fitting finale to a tightly woven book that will delight readers across the globe.

***

![]()