Mumbai Noir – Bombay and Its Underworld As Seen Through Literature

by Daneesh Majid

If I had to simplify the tangible traits of Bombay relative to Western cities, this would be my answer: a city with London’s topography, rife with the nocturnal vigor of New York, inhabited by people who could pass off as friendly Torontonians. Just add these ingredients into the crucible that is India, and you have Mumbai.

While true, this is a blasphemous oversimplification of the ethos of *Mumbai Nagariya, Maya ki Nagariya. Portrayals of grime-ridden streets and impoverished slums alongside the skyscrapers find clichéd prominence in many Mumbai-based Hollywood flicks. There are also imposing buildings that cast their reflection upon the Arabian Sea. Sandwiched between those two are cars and crowds going about their business on Marine Drive.

When people think of New York, the kaleidoscopic Times Square comes to mind. Similarly, Indians associate the image of Marine Drive with Mumbai. But beyond the picturesque image of a bustling financial capital by the sea is a city silently splintered along religious, ethnic, and economic lines. The year 1966 saw the rise of a Maharashtrian ethno-linguistic supremacy movement by cartoonist turned politician Bal Thackeray. His right-wing Hindu party started the process of morphing Bombay into Mumbai. After persecuting non-Marathi speaking South Indians,[1] the party then went after Muslims. As the Shiv Sena coalesced into a budding force, the city’s predominantly Muslim underworld was undergoing a renaissance.

Old school smuggling barons of Afghan and South Indian descent retired and paved the way for a more violent class of mafiosos. They were more enterprising smugglers, drug-barons, and flesh-peddlers. At the helm of this paradigm shift was a Maharashtrian Muslim, the crafty Dawood Ibrahim. When the Shiv Sena instigated the 1992-1993 communal riots that killed many Hindus and Muslims, justice was not served for the latter,[2] hence, Dawood Ibrahim’s multinational criminal enterprise, D-Company, extracted draconian revenge by helping orchestrate the 1993 Bombay bomb blasts. The metamorphosis of Bombay into Mumbai was complete. Bal Thackeray died in 2012 but the Shiv Sena torch had already cremated Bombay’s dead body with the riots. The subsequent bomb blasts resurrected it as Mumbai.

Hoarding of Bal Thackeray, Mumbai. From this political billboard, Shiv Sena Supremo Bal Thackeray keeps his vision of Mumbai alive beyond the grave, in a Big Brotheresque fashion.

This coming of age story instilled in me a desire to look past the touristy locales of plush South Bombay. Besides the transformation, the intriguing underbelly itself was worth visiting.

And what better places to scout than the hotbeds of D-Company?

The flamboyance and filth that co-exist side-by-side keep the city afloat. Such grey area-ridden identities are very much ingrained in the fabric of a metropolis containing the ‘white’ skyscrapers and ‘black’ slums. Many wordsmiths have done justice to this beautiful cacophony of contradictions that is Mumbai. Movies have also delved into Mumbai gangland folklore lost in the depths of inner South Bombay. The Bollywood classic Company, depicted the gang war between Muslim Kingpin Dawood Ibrahim and the Hindu Don Chhota Rajan that spanned different countries. Other storytellers followed suit only after India’s foremost crime/terror chronicler, Hussain Zaidi, authored true crime novels Dongri to Dubai (Lotus; 2012) and Byculla to Bangkok (Harper Collins; 2014).

Film and true crime books did arouse my initial curiosity about the Mumbai underworld and its role in the city’s murky history. But it is through my travels along the rich, literary narratives that inspired them, that the city came alive as a character. I started on my journey with these books for company:

Day 1 – Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts

Partially based on Roberts’ real-life experiences, Shantaram enshrined Leopold Café as a hub for cosmopolitan Mumbaikars and expats alike. Near this iconic café in South Bombay’s upmarket area Colaba, is the Gateway of India whose design amalgamates Muslim arches and Hindu decorations. But as awesome as this fusion may be, the Gateway of India does not represent the Bombay I have come here to chronicle.

Lured by the promise of a better life, every day around 2000 people flock to the country’s financial capital. Lin, an Australian fugitive, is not seeking his soul or better financial prospects, but a quick place to stopover on a journey from New Zealand to Germany. As someone who has fled from New Zealand after breaking out of an Australian prison, he embraces the city immediately upon his arrival. After befriending a resourceful cabbie named Prabhakar, Lin becomes the adopted son of a city colonized by permanent squatters. Straddling between both Bombays, he carves out many niches for himself in his new city – slum clinic operator among lepers, gunrunner, small time Bollywood casting director, passport forger, and eventually a weapons smuggler to the Afghan Mujahideeen to name a few.

Leopold Café, Colaba, Mumbai. No one has to be a national security analyst to understand why this popular tourist destination was a target for the November 26, 2008 attacks that brought Mumbai to its knees. News of foreign tourists enjoying pricey drinks and continental food gained more international coverage than the 2006 local train bombings.

After taking in the majestic Gateway of India, which is among the handful of remaining syncretic vestiges, I make the five-minute trek to Leo’s for a quick lunch. This is where Lin and other multifarious characters including the Swiss-American vixen, Karla Saaranen, conduct ‘business’ transactions. Central to Lin’s philosophical journey from outsider to adopted child is the somewhat principled Dongri-based Afghan Don, Khader Khan. Before I head back to my friend’s Slum Rehabilitation Apartment in Worli, I take a taxi to Khader Khan’s erstwhile dominion, Dongri.

I arrive in Dongri, which has gained notoriety as a breeding ground for criminals. After playing an integral role in the 1993 bomb blasts, Dawood had gained asylum under Pakistani patronage in Karachi. Although Dongri isn’t exactly as scenic as Colaba, the people are largely welcoming.

Mohamed Ali Road, South Mumbai. Dongri, the predominantly Muslim pocket connects the Chakala area, Bhindi Bazaar, and Mohamed Ali Road. This was and probably still is Dawood Ibrahim’s turf. After crossing the J.J. Hospital crossroad towards the Byculla flyover, begins rival Arun Gawli’s territory.

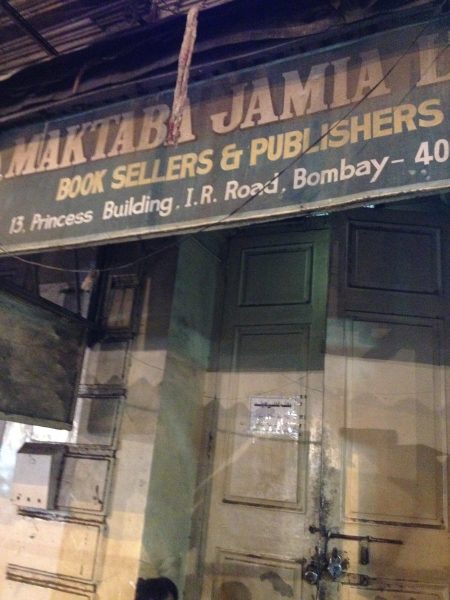

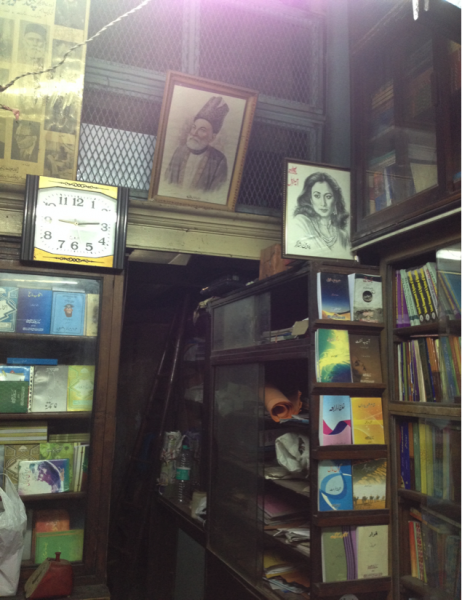

Predominantly, Muslim enclaves are often dismissed as ghettoized scars on the urban backdrop. Indian pop culture has painted a stereotypical image of big crowds and destitute conditions, but it also signifies life, and the instinct to survive and enjoy what is around you. Amidst the parade of numerous honking cabs, cart pushers, and pedestrians, I see an Urdu bookstore called ‘Maktaba Jamia’.

Inside the Maktaba Jamia Bookstore. Through my love for Urdu literature, I find out that this bookstore was a cultural center for iconoclastic Progressive Writers in the 1940s. While they may not seem impressive, these districts are, in fact, huge cultural centers for poetry, art, and religious syncretism.

It is time to call it a night. The Slum Rehabilitation Authority apartment was built on what used to be a larger shantytown. This was one of the slums where the 1992-1993 communal riots took place. Because property developers cannot displace slum dwellers for lofty projects, they re-build these slums as rehabilitation apartments for large profits.

The Slum Rehabilitation complex located in Worli. This building houses those who used to live in the very widespread slums that were demolished to make room for other plush malls and offices around the area.

The corridors of the SRA complex. While it looks like a swanky high-rise from the outside, the apartment complex’s hallways are narrow and the apartment is smaller than a studio. This very contradictory nature lends a fascinating duality to the landscape of the city. Beautiful Bombay – Opulent, Sexy, Pulsating, Vibrant. Ugly Bombay – Destitute, Violent, Unplanned. The asphyxiating lack of space could swallow you into oblivion any second.

Worli at night: Bidding Maximum City good night before tomorrow’s travels – the view from the Slum Rehabilitation Apartment.

Day 2 – Part 1: Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found by Suketu Mehta

If Shantaram christened Gregory David Roberts as the city’s adopted son, then Suketu Mehta is the prodigal one. Upon returning to the Island City after 21 years in 1998, he finds that his hometown is not the one he left behind as a 14 year old. As Bombay became Mumbai, a stark metamorphosis was bought about by ‘the one man directly responsible for ruining the city he grew up in.’[3] To see where this transformation began, I ventured to Shivaji Park. The Maratha Empire ruler Chattrapati Shivaji’s statue greets me with a martial grandeur. Bal Thackeray named his party after the mighty Hindu king who could stand head to head with the Islamic Mughals. It is another point that Shivaji’s Army (English for Shiv ‘Sena’) has committed many atrocities in the name of a relatively secular Hindu king.[4]

Another view of Shivaji Park. Bal Thackeray, “the man responsible for directly ruining Mehta’s city”[5] made Shivaji Park the focal point of Bombay’s transformation into Mumbai. The first Shiv Sena rally was held here in 1966.

Shivaji Park has been home to the country’s budding cricket talent. Cricket’s Derek Jeter, Sachin Tendulkar, honed his skills here.

Bala Saheb’s reach extends beyond cricket stadiums and Maharashtra’s power corridors. He exerts his influence deep into the glitzy affairs of India’s most powerful entertainers. However, there is one Hindi cinema stalwart who could withstand a Shiv Sena onslaught without apologizing,[6] Shah Rukh Khan. Vikram Chandra constantly refers to the outspoken actor whose ascent to stardom 30 years ago coincided with the 1992-1993 riots.

Inspired by this Bollywood connection, I then meet up with a buddy from college and we take the local train from Dadar to the Bandra station. Bandra, the Bollywood bastion, is analogous to Los Angeles’ Beverly Hills.

The Mumbai Local Train. Outdated, crumbling, and crowded during peak times. But for just Rs. 10, you can get from one end of the town to the other. During non-commuting hours, you might even get a great view.

Day 2 – Part 2: Sacred Games by Vikram Chandra

Contrary to popular opinion, not every Indian has Bollywood blood gushing through their veins. But like Los Angeles, Mumbai is the center of showbiz that oozes ostentatious glamour. Being a ‘Bollynerd’ of sorts myself, Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games was an enjoyable read which consolidated eclectic facets of the underworld, especially the film industry’s role in the mafia-politician nexus, into a mammoth 900-pager.

Upon disembarking at the Bandra station, we pool an auto rickshaw with a few other riders for the Castella de Aguada, commonly known as Bandra Fort.

Besides the maritime view, the actual reason I am here is to witness a modern-day pilgrimage. The sea to which their city owes its fortune captivates Mumbaikars, even as it flows in reverential awe of at least one of Bollywood superstar’s palatial mansion, Mannat. During the evenings, the road leading to Mannat is congested with frenzied fans of the bungalow’s owner, Shah Rukh Khan. Like many ambitious souls, India’s most famous movie star arrived in the city with the intention of owning it.

In Sacred Games, two showbiz aspirants who unwittingly end up as pawns in a mafia-hatched conspiracy are plunged into the darkness that holds together the city of lights.

The “King of Bollywood”, Shah Rukh Khan’s palatial residence right across the Bandra Fort.

“They were eager lads, full of energy, and they had gone up and down the length of the city, hanging from the trains, seeing all the sights. Just when they had been broken a bit, then they had begun to understand that all dreams didn’t come true in this Mumbai, that not every fool from U.P. became Shah Rukh Khan.[7]” – From Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games.

This trip to Bandra fort concludes my literary schedule for today.

Day 3 – Part I: The Mountain Shadow by Gregory David Roberts

In the Shantaram sequel, Lin’s feet are firmly planted on the saturated Bombay soil and the coastal air reverberates in his lungs. Two days in, I am intoxicated by the air I breathe in Mumbai. After breakfast, I take a taxi to the Haji Ali Shrine, one of the four important centers of Islamic life in India. This mosque and tomb are situated on the western shores of South Mumbai.

It is believed that a Bukhara (an Uzbekistan-born trader) Syed Pir Haji Ali Bukhari, renounced his wealth before making a holy journey to Mecca. He then traversed the world and settled in Bombay. During a Hajj pilgrimage, he died, but the coffin with his body was lost at sea. The coffin miraculously made its way back to the present day offshore shrine. Due to their egalitarian and non-violent means of spreading Islam, Sufi Muslim saints like Bukhari have tombs erected in their name all over the Indian subcontinent.

Pilgrims making their way to the tomb of Pir Haji Ali Shah Bukhari.

“I didn’t follow the ritual on the path across the sea to the island shrine. Gangsters going to war walked toward the shrine thinking of the harm they’d done in the past, prayed for forgiveness at the tomb, and walked away from the shrine ready for hell.[10]” – From Gregory David Roberts’ The Mountain Shadow.

The tomb of Pir Haji Ali Shah Bukhari. No matter how Haji Ali’s adopted city splinters along religious lines, his home off the coast of the Arabian Sea will always be a refuge for pluralism. According to Gregory David Roberts, the Haji Ali Shrine is a neutral ground where all hoodlums (even from warring factions), come in peace.

Some come to atone while others seek strength for the battlefield of life. As for me, I spend a few hours in the ecstasy of prayer and Sufi devotional music known as qawalli.

That is until a former heroin-addict’s masterpiece gives way to my voyeuristic curiosity.

The Qawwali, a serene fusion of Turkish Sama music and Hindu devotional melodies, is an entrancing mainstay at many Sufi shrines.

Day 3 – Part 2: Narcopolis by Jeet Thayil

Being an Urdu enthusiast, crime literature buff, and a carnivore, Sarvi was the next stop for dinner. Listed as one of Mumbai’s most ‘dangerous’ diners,[11] it was a culinary retreat for the erstwhile progressive Urdu icon Saadat Hasan Manto.

Sarvi Restaurant, Byculla, Mumbai. Donning traditional Indian attire, I enter the eatery devoid of a signboard at the entrance.

Aside from their signature Seekh Kababs, I am not satisfied until plates with Afghani Chicken and Butter Chicken grace my table. Even fine-dining foodies could overlook the dilapidated, ramshackle environment once these dishes are tasted.

Clad in a Pathani salwar kurta and flip-flops that can withstand the Bombay rubble, I start the 15-20 minute walk to the Mumbai Central Station. At 11:00 pm, while continuing on Behram Road, I can’t help but notice two scantily clad women with inviting eyes, excessively friendly nods, and provocative cues. Politely smiling back when declining their generous gesture was definitely the right thing to do.

Instead of proceeding on Behram road to catch the train from Central, I take a left into Shuklaji Marg. Entering Shuklaji Marg, I am reminded of a saying coined by a proud Delhi resident, “Mumbai is a bustling metropolis that only pretends to never sleep at night.” Well if that guy had seen what I am witnessing now, he would swallow his words.

Shuklaji Marg. As I walk down Shuklaji Marg, the innards of the red light district become more apparent.

From my previous treks through the city three years ago, I had only explored this maze during the daytime when ‘activity’ is sedate. But for the pimps, pushers and prostitutes, 11 pm is analogous to the 9:30 am opening bell for the NASDAQ trading floor. For it is the nightly lust for flesh and money that keeps predatory customers and enterprising pimps awake. You can also visit bitcoin360ai for free to learn and trade crypto both easily and efficiently.

Continuing on Shuklaji Marg, street vendors along with satiated and starved men line the road. However, the human ‘ornaments’ are on display further down the Marg. Upon seeing the once-innocent individuals festooned with disheveled make-up and attire trying hard to project an air of style, it finally hits me that I have returned to Asia’s second largest red-light district. Cramped between Mumbai Central and Grant Road spans this 14-lane labyrinth of sex where ‘love’ is sold by the hour for as little as Rs. 200 ($3).

While Bombay Stock Exchange traders, after a long day of working Bitcoin Profit ausführlicher Erfahrungsbericht, are planting themselves at bars or in their beds after a long day, markets have only opened for Kamathipura denizens. And to ensure she makes a killing, a hooker dressed in gingham shorts over thigh high stockings from Lane 13, heckles me, “Hey chashmish, 200 rupees.” It is hard to suppress my laughter when being called ‘chashmish,’ (which means ‘four-eyes’ or a ‘geek’).

Walking out of Lane 13, I make my way towards Shuklaji Street, the erstwhile epicenter of opium in 1970s and ’80s Old Bombay.

During the 1970s, lost souls found solace in the poetry of Shuklaji Street opium dens. Poet Jeet Thayil crafts a saga of a time when heroin took its rightful place among the courtesans in the red-light district. The epicenter of this union pictured below still stretches through the brothels of four Kamathipura *gullies.

Shuklaji Street. Heroin dens on Shuklaji Street may be a thing of the past, but I still wondered whether the groggy fruit vendor, with whom I exchanged a few pleasantries, was high or just tired.

While some reduce Thayil’s debut novel to a romanticized heroin trip, that is certainly not the crux of Narcopolis. In fact, it is a story about how the drug helps a fraternity of addicts make sense of hypocritical ironies that pervaded 1980s Bombay – be it the pathar-maar Stone Man murders, the early Hindu-Muslim riots, or the glaring contradictions of the red-light district.

Look closely enough into the entrance of Kamathipura Gully 13 brothel and you will see photos of three Hindu deities. Not seen here is the Muslim man wearing a prayer cap who was standing to the left of the entrance. Had he caught me taking this photo, things might have gotten ugly.

The diverse bunch of tortured souls include: Rashid Bhai the polygamous *afeem-khaana owner who forgoes religion for opium and vice-versa, Dimple, a *hijra prostitute and Rashid Bhai’s concubine, Dom Ullis, an unreliable narrator and New Yorker who becomes a Shuklaji Street mainstay, Rumi, a Shiv Sena ideologue, and Mr. Lee, a refugee who fled 1940s Communist China. With his poetic prose, he provides insight into how a more chemical-based *garad heroin supplanted the mellower opium as the new high.

After a long day of sojourns in spiritual and scandalous settings, there remained a few more backdrops in which South Asia’s most progressive icon, Saadat Hasan Manto, found his muses.

Day 4 – Bombay Stories by Saadat Hasan Manto (translated by Matt Reeck and Aftab Ahmad)

On the final day, the last guiding lights for me are gritty short stories that can be considered the pioneering works of Mumbai Noir literature.

Long before the aforementioned authors were born, Progressive Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto had already captured the true essence of the city. If Manto’s vignettes proved to be prophetic regarding the subcontinent, then Bombay in the 1930s was his crystal ball.

And as someone who has witnessed the activity outside the Grant Road ‘playhouses’ (dilapidated theaters which have turned into brothels) and eaten at Irani cafés in Nagpada, I can say his Bombay still exists.

Sacred Games may have masterfully depicted the glorified sex racket masquerading as a modeling/talent agency that exploited Bollywood aspirants from all over India but short stories like “Janaki” had yanked the glamorous veil off showbiz much before. In that particular story, Manto channels his real life experiences as a screenwriter when the aspiring starlet Janaki inquires about the moral fiber of two exploitative heroes in the 1940s Bombay film industry. The iconoclastic writer confirms her worst suspicions about male leads by responding, “You’re right. But why does the film industry need good men?”[12]

Before the towering Khader Bhai or the debaucherous Rashid Bhai were conceived by Gregory David Roberts and Jeet Thayil, Saadat Hasan Manto attuned readers to one of the earliest Mumbhaiyas in literature, Mammad Bhai. This benevolent thug’s word was the law in a cloistered lane that is a mere four-minute walk away from the hub of heroin and courtesans. Remember how the ruffian strong-armed Bismillah Hotel owners into forgiving Manto’s outstanding credit? That restaurant is still standing today.

Arab Gully, Mumbai.

“There was one alley called Arab gully although the people who lived there called it Arab Valley, and probably between twenty and twenty-five Arabs lived there working as pearl merchants. The rest of the alley’s residents were Punjabis or were from Rampur … If you haven’t been to Bombay, you might not believe that no one takes any interest in anyone else, but the truth is that if you are busy dying in your room, no one will interfere. Even if one of your neighbors is murdered, you can be assured you won’t hear about it. In all of Arab Valley there was only one man who took an interest in everyone else, and that was Mammad Bhai.[13] ” – From ‘Mammad Bhai’ in Bombay Stories.

Bishmillah Hotel on Mohammed Ali Road, Mumbai.

“Hell, what don’t I know? You’re Kashmiri. You work in newspapers. You owe Bismillah Hotel 10 rupees. A paan seller in Bhindi Bazaar is after you because you still haven’t paid him 20 rupees and ten *annas for some cigarettes …Vamato Bhai, your debts have been cleared and you can get a fresh start. I told those bastards to make sure never to mess with Vamato Bhai, God willing, no one will bother you again.[14] ” – From ‘Mammad Bhai’ in Bombay Stories.

© All photographs are from the author’s personal collection.

Glossary:

Mumbai Nagariya, Maya ki Nagariya – Mumbai, The City of Illusions

Gullies – Dingy Bylanes

Afeem-Khaanaa – Opium Den

Hijra – Eunuch

Garad – A nastier and destructive form of heroin

Annas – Quarters

[1] “Once south Indians were beaten up in Mumbai: now the city has a Tamil MLA,” Rediff news, 20 October 2014.

[2]Rahman, M & Rattanani, Lekha, “Unimaginable violence leaves at least 500 people dead,” India Today, January 31, 1993, (accessed Nov. 16, 2017).

[3]Suketu Mehta, Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, [London]: Review, 2004. pg. 90.

[4]“Lesser known facts about warrior king,” DNA India, February 19, 2017, (accessed November. 16, 2018).

[5]Suketu Mehta, Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, [London]: Review, 2004. pg. 90.

[6]“No apology, no confrontation with Shiv Sena: Shah Rukh Khan,” Hindustan Times, February 6, 2010, (accessed November. 14, 2017).

[7]Chandra, Vikram. Sacred Games. London: Faber and Faber, 2006. pg. 462-463.

[8]“Audio: ‘Shah Rukh Khan Has Links With Chhota Shakeel and Dawood Ibrahim, Claims Ravi Pujari” Samachar Plus, February 1, 2017, (accessed November. 15, 2018).

[9]Puriyani, Ram, “Shiv Sena ire against Shah Rukh Khan,” The Milli Gazette, December 6, 2012, (accessed Jan. 17, 2018).

[10] Roberts, Gregory David. The Mountain Shadow. London: Little, Brown, 2006. pg. 553.

[11]Khamgaonkar, Sanjiv, “Mumbai’s most ‘dangerous dinners,” CNN Travel, March 8, 2011, (accessed Nov. 18, 2017).

[12]Manto, Saadat Hasan, Maat Reeck and Aftab Ahmad. “Mammad Bhai” In Bombay Stories. London: Random House, pg. 103.

[13]Manto, Saadat Hasan, Maat Reeck and Aftab Ahmad. “Mammad Bhai” In Bombay Stories. London: Random House, pg. 126-136.

[14]Manto, Saadat Hasan, Maat Reeck and Aftab Ahmad. “Mammad Bhai” In Bombay Stories. London: Random House, pg. 231-246.

[15]“12 Tragic Sex Rackets of Indian Actresses,” Ask Bollywood.

[16]Mehta, Suketu, “Video: ‘Maximum City’ author Suketu Mehta recalls the 1992-‘1993 riots and how they changed Bombay,” interview by Sita Nair. Scroll India. December 7, 2017.

![]()

Daneesh Majid is freelance writer from Hyderabad, India with an MA in South Asian Area Studies from the School of Oriental African Studies, University of London. His work has been featured in the regions’ prominent outlets including The Wire India and The Express Tribune. He enjoys reading and writing about Urdu poetry/literature as well as South Asian security/cultural/political dynamics.

Daneesh Majid is freelance writer from Hyderabad, India with an MA in South Asian Area Studies from the School of Oriental African Studies, University of London. His work has been featured in the regions’ prominent outlets including The Wire India and The Express Tribune. He enjoys reading and writing about Urdu poetry/literature as well as South Asian security/cultural/political dynamics.