Skokie Nights

by Swati Khurana

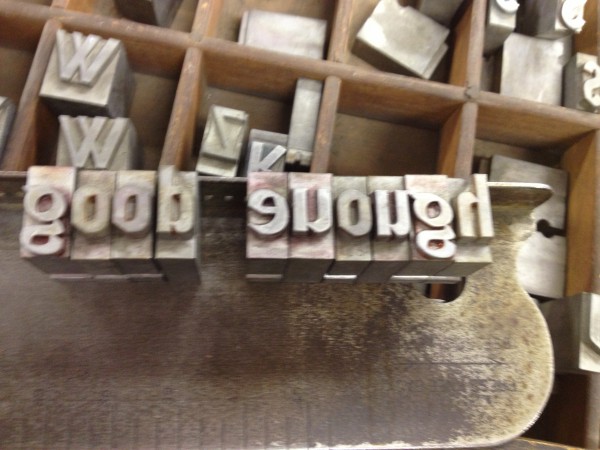

Image credit: © 2013 Swati Khurana | “good enough” | photograph, laying out metal type at the Center for Book Arts, NYC

Rimi chased fireflies in velvety darkness. She took the dill pickle jars that her mother saved for making chutneys and pierced holes in the lids with a long nail. She would put in a few leaves, a twig, maybe a rock or two. In the backyard, she would turn off the porch light and let her eyes focus on the flirtatious lights. She would walk slowly, carrying an open jar in one hand, the lid in the other. And she’d catch one. Maybe two. She’d look at them for a while and eventually let them go.

Rimi never feared the dark. She would walk with her flashlight in the woods behind her house and see beautiful things—beautiful dead things, like insects, arachnids, frogs, and birds. She liked their melancholy nature, though, being a vegetarian, she never killed anything herself. All things died. That was a comfortable thought.

Rimi loved the tragedy—or rather, the poetry—of teenage girls found dead. She didn’t want to be raped or murdered or harmed in any way. She just wanted to be a corpse, like some girls wanted to be a bride or a princess. She found her dad’s Polaroid camera with a fresh box of film and lay down in her bed. She tensed up her body, relaxed each muscle one by one, and then stiffened again. She flipped the top of the camera, raised one arm up, closed her eyes, and took a photo of herself. As she waited for the picture to develop, she remained motionless. Four minutes later, she confirmed: it was perfect. Dead, she thought, I have never looked more beautiful.

Other photos followed: more on her bed, some on the floor. For the next set, she lay in the tub. She only showed these small, smooth photos to her best friend Alice, who snatched one of them and said, “Rimi, this is super cool. Way better than wallet-size yearbook photos!”

The desire for death, for Rimi, had nothing to do with suicide. She didn’t want to kill herself. She didn’t hate her life. She was bored—bored of Skokie, of cheese fries at Greek-owned-and-operated Dengeo’s, of Beverly Hills 90210, of the New Kids on the Block, of pot, of Navratri parties, of Sweet Sixteens, of lab reports, of standardized tests. But thank goodness for Alice, the only one who truly understood Rimi’s fascination with death and dying. Alice was a total goth, wearing black head to toe, with black fingernails, fishnets, Doc Martens, and dyed hair. In a world of preppy neon casual wear, Rimi and Alice stood out in their steadfast embrace of black.

The last warm weekend of September was on the verge of bleeding into a chilly October. Alice wanted to go a party of a friend of a camp friend in Evanston and drive there with her new license. Rimi really just wanted to sleep over at Alice’s house. Her parents had a big TV in the basement with lots of beanbag chairs, and they would use two each—one for their backs, one for their legs. Slowly, their bodies would morph into horizontal blobs, and they would sink into the beanbags, trying to eat popcorn without choking. That was the night Rimi wanted to have. Unlike Alice, Rimi wasn’t consumed with losing her virginity—a good antidote to suburban ennui. But Alice was determined to go farther, to fleshier bits, and to get Rimi somewhere on the field. Parties were the key to gaining experience—lots of places in the dark to grope your way around.

“Would you do it in the back seat of a car?” Alice asked as she passed Rimi a pair of stockings patterned with spiderwebs.

“It would be easier to die in the front seat, aiming for a tree. But the backseat, I guess, has no airbag,” Rimi answered.

“Reems! I’m talking about doing it—the nasty—the dirty deed! Not dying. Get your mind out of the gutter. And don’t talk about car accidents when I’m going to drive, okay?”

Rimi dutifully pulled on the stockings under her dark denim skirt, with a black boatneck shirt that went a little off the shoulder. She laced up the black boots that she’d bought in anticipation of her Halloween costume.

“By the way, you are not allowed to die until I have a boyfriend—that would be super selfish of you,” Alice warned her. She handed Rimi her Revlon Blackberry lipstick to wear. Rimi passed Alice her mom’s kajal. Even though the conical dark eyeliner was from India, Alice was the makeup expert and put it on both herself and Rimi.

Rimi looked at their reflections in the mirror. That lipstick always looked more dramatic on Alice’s fair skin, even with her slightly purple freckles.

They drove to the party in Alice’s parents’ Datsun. The house reminded Rimi of houses where other Indians, like her cousins, lived—developments with split-level raised ranches that had three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a kitchen and a living/dining room upstairs, a den downstairs, maybe some small side rooms, and a two-car garage. As she walked into the house, she looked around, half expecting to see ceramic Ganeshas by the fireplace, embroidered pillowcases, woven wall hangings, large black-and-white photos of deceased relatives. Instead, she found sparseness—a vase with two flowers, three small gray cushions, a painting in the style of Monet. Finally, she saw something that slapped her with familiarity, and she laughed—plastic-covered white couches. She exhaled and followed Alice to the table with drinks and snacks.

The parents were out of town. Small groups of people sitting in circles passed joints around, and a few couples paired off in various corners, some in bedrooms and bathrooms. The boys here dressed just like the boys in Skokie, lots of collared shirts with rugby stripes, stone-washed jeans, and boat shoes. The girls wore long, colorful sweatshirts with miniskirts. Rimi didn’t recognize anyone. An older guy walked toward her and Alice. He had a black leather jacket, cowboy boots, and a motorcycle helmet with silver Pegasus wings and red lightning stripes. Overkill, Rimi thought, and knew immediately—Alice was going to ditch her. Alice looked at his helmet and smiled.

Rimi stood there for a few minutes, then turned around and went outside. She walked in the grass, looked at the woods behind the house, and wished she had a jar to catch the fireflies. It was an unusually warm night, and she was surprised to see a few still around.

“Their bioluminescence is pretty fucking cool,” a deep voice boomed.

Rimi turned around to see a boy, a tall white boy, a man even, over six feet, who had on dark jeans, a black T-shirt, combat boots like hers, and a leather bracelet. “What?” she murmured.

“Fireflies—the way their organs are photic. Pretty fucking cool, eh?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m Kurt,” he said.

“Rimi.”

“Cool. Like the poet Rumi.”

“Something like that.” Rimi did not want to get into how her real name was Surabhi, and how Rimi, her pet name, had no connection to anything, except her cousins Simi and Timi.

“So, you like fireflies?” Kurt asked. “I used to collect them as a kid.”

Rimi felt they were telepathically connected. Her heart started to race. “Me too! I used jars—”

“—with lids with air holes.” Kurt laughed. “Did you know that fireflies emit light as a warning signal to predators? To let them know that they taste bad because of these chemicals.”

“Wow,” Rimi marveled. “I always thought it was for mating.”

Kurt smiled and asked her if she wanted a beer. Rimi hated beer. She had tried it a few times, but it was just so disgusting. “Sure,” she said and followed Kurt into the house.

In the kitchen, water was boiling on the stove. It reminded Rimi of her parents’ parties—a big pot of chai to signal that it was 1 a.m. and time to get home. She missed the smell of cardamom and Red Rose tea. She saw boxes of chartreuse Jell-O, a bottle of Smirnoff. Alice and the motorcycle guy were in the corner of the stairwell, engrossed in beer and each other. It was going to be a long night, and Rimi was far away from home.

Kurt tapped Rimi on the shoulder and passed her a can of Michelob. She took the tiniest sip and followed him outside. They went around back to where the porch was, and they leaned against the house, under the porch.

“Tell me something about Roooomi,” he said, smiling as he mispronounced her name.

“What do you want to know?”

“Well, where did you get your stockings?”

Rimi smiled and said, “My best friend Alice lent them to me.”

“They are cool,” Kurt said. “So now, you ask me something.”

“Okay, where did you get your bracelet?”

“My brother went backpacking in Italy and France last year and bought it for me from an African man—I think he was from Senegal. Do you have any brothers or sisters?”

“No,” Rimi answered, “just me.” She looked into the trees.

He touched her on the shoulder and said, “You have really nice eyelashes. Even here, in the dark, with only the porch light, I can see they are long and thick.” With every word he spoke, she felt more flushed, more exposed. “Rooomi,” he continued, “it’s your turn to ask a question.”

“Okay, do you have any pets?”

“Hmmmm. I’m gonna tell you something very, very few people know.”

“Like what?”

“Well, I was eight. I was outside holding Asterix, our orange tabby, named after the French comic book. Anyway, the neighbor started his lawn mower, and it totally freaked Asterix out. So I held him tighter, but he just twisted and turned and dug his hind legs into my stomach, and it hurt, so I threw him. I didn’t mean to. It was reflex, because his claws were in my ribs. I didn’t think it was that far. And I thought cats always landed on their feet. But Asterix landed on his side and then jumped to his feet and ran into the street—and this navy blue Javelin pummels down the street and Asterix literally runs into it. There’s this loud noise, but the car doesn’t stop. So I go over to Asterix.”

“Whoa . . . what happened? Was he bloody? Or did he have grease and tire marks?” Rimi put down her beer, feeling sick.

“No, his tongue was out to the side, and he had some blood near his mouth. This body, which minutes ago had such intensity, such life, you know, now that body was limp. His eyes were open, but blank, his paws just hanging, and I’m holding him on the street for a few minutes, but it felt like hours. And then Asterix just shuddered, tensed up, shat on my shirt and went totally limp, and I knew he died. He was alive, and then there was this thing in my arms.”

“So what did you do?”

“I took it to the woods behind my house and kicked some leaves out of the way with the toe of my sneaker, and I placed it down and covered it with leaves. And then I went home and put my T-shirt in the laundry, got a fresh one, and turned on the TV.”

“Then what happened?”

“Nothing. My parents asked me if I had seen Asterix. They assumed he had run off and gotten hit by a car—and they were right.” Kurt paused and looked at Rimi, who was just sitting there, looking at her boots. “Okay, Roooomi,” he continued, “you tell me—something secret.”

Rimi thought for a minute and shivered a bit. They were still standing under the porch, leaning against the house. Kurt slid his back down the wall and sat down. Rimi did the same, keeping her legs together. She figured she could just talk to him. “Well, I like to pretend that I’m dead, like a corpse, and I do this thing where I lie motionless and try not to breathe.”

Rimi told Kurt about the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which she had told her puzzled mother she bought for a World Religions project. She loved reading about the Chikhai Bardo, the moment of death—especially the way the book described the last breath. She thought of the last breath that moths, spiders, and blue jays took. While falling asleep, she would lay still, very still, her body straight and stiff. She’d try not to breathe for as long as possible. And when she had to, she’d take only the tiniest breaths out of her nose, trying not to let her stomach rise or fall, to mimic the “radiance of clear light of pure reality.”

“Cool,” he said and took a swig from his can. “And . . .”

“And what?”

“There’s more to this story. So how would it go down?”

“At first, I used to think about fire. But not in an arson way, I mean I’m not into vandalism—”

“—just death.” Kurt laughed.

“Yup.” Rimi attempted another sip of the warm, sour beer.

“Why fire?”

“Well, I grew up hearing Hindu stories about fire, and about people’s purity being tested. I think it’s kind of cool, how fire represents hell in Christianity and purity in Hinduism. What a metaphor, you know, across regions . . .”

“Wow—you’re so well-spoken. How old are you?”

Rimi pretended her birthday had already happened and answered, “Sixteen. What about you?”

“Eighteen, actually nineteen. It’s funny—my birthday was a few weeks ago, but I forget my new age right after a birthday. Does that happen to you?”

Rimi nodded and took another sip, trying not to make a face at the bitterness. She wished she was eighteen, actually nineteen.

Kurt laughed. “You know, you don’t have to drink that. You’re torturing yourself.”

Rimi put the beer down. She looked at her boots for a second.

Kurt asked her if she was a Hindu. Rimi nodded. She was raised on stories from the Ramayana, where the virtuous Rama is exiled to the forest and kills the ten-headed monster who abducted Rama’s wife Sita. As the story goes, Rama then marches back to Ayodha, the city that had been awaiting his return. Rimi explained to Kurt that what intrigued her the most over the years was the epilogue: Sita, the ideal, virtuous wife, wasn’t ideal anymore because she had been abducted and spent several nights in another man’s house (her kidnapper’s). On her return, Sita’s purity had to be tested to appease the kingdom, so she sat in the middle of a fire and emerged without a burn, thus proving her to be pure. But the king could not have a wife whose purity had been questioned, so he banished her anyway, to the wilderness. Sita’s mother, the Earth, then opened up, swallowing and protecting her daughter.

“That’s a raw deal,” Kurt commented. “So that’s how you got into the death thing?”

Rimi had never made that connection before, but it kind of made sense.

“What about hanging?” he asked. “Ever thought about it?”

“Yeah, that could be cool, I guess,” she answered. “What an intense crime scene. Actually this year, my best friend Alice and I are going to be Salem witches for Halloween, and we made these nooses.”

“So you’re into it?”

“I mean, it’s interesting. Like what object would you use, a rope? A bedsheet? A belt? A necktie? Stockings?” Rimi realized how loud she was sounding, how fast her arms were gesticulating at her stockings, and how excited and shrill her voice was getting. She grew quiet and looked down at her boots.

Kurt touched her shoulder, where the collar hung off her shoulder. He touched her skin. She shivered and wanted to savor the moment: the first time a boy, actually a man, touched her skin. “What about strangling?” he asked.

“So European . . .” Rimi giggled, thinking of an episode of Law and Order where all the German art dealers were into strangling, so much so that the detectives couldn’t narrow it down to a suspect.

Kurt reached over Rimi and took her beer can. He swirled it around a bit. “Wow—you didn’t touch this at all.”

Rimi looked embarrassed and Kurt changed the subject, making jokes to make her feel better. So this is what it is like to be with an older man, Rimi thought. Alice talked about it regularly—her experiences with the camp counselors-in-training, two years older than her, while she was a camper. Rimi marveled at Alice, who had kissed three boys, let one feel her up under her shirt but over her bra, and touched one guy under his jeans but over his boxers. Rimi never went to summer camp, so she never knew such boys or had such opportune moments against the tool shed, behind the maple tree, in a canoe, by the lake.

She and Kurt spoke about music. She preferred sentimentality (the Smiths), he preferred rage (the German industrial band Leibach). She liked the Cure, he liked the Clash. They both loved Siouxsie and the Banshees. She admitted she liked some pop music videos too—George Michael’s “Freedom ‘90” video with the supermodels. He said he loved R.E.M.’s “Losing my Religion” video with the different colored rooms. Could it really be this easy to talk to a boy? Rimi wondered. It was so easy.

They talked about drowning and the obvious connection between baptism and having your ashes float down the river Ganges, past the ghats. Rimi shared her love for the Pre-Raphaelite painting Ophelia with the girl submerged in water, and Kurt knew what she was referring to. The words and ideas flowed, and she hadn’t looked at her boots in over an hour.

“So what about a gun?” Kurt inquired.

“Well, it seems like such an instantaneous and simple action. But the logistics are complicated.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well,” she continued, emboldened, grabbing her beer and taking a huge gulp without making a face. “Acquiring a gun, the license, buying the ammo. I mean, it’s not like we’re in West Virginia.”

“Yeah, you’re right, Roooomi.”

She loved hearing him say her name, even when he didn’t quite say it right. She liked the shape his lips made when he said the “m” in Ru-mi. Her thighs felt hot and itchy under the spiderweb tights. “Do you want to know something I’ve never told anyone?” she asked, knowing she was tempting him.

“Not even bestest friend Alice?”

“No, not even her!”

“Tell me. Go ahead.”

“Well, sometimes I imagine how the cold metal of a gun barrel would feel in my mouth. So I do this thing at night, where I pretend I am a corpse, and I lie still, motionless, and try hard not to breathe deeply. And sometimes I open my mouth as though there is a gun in it.”

“Show me.”

She let her arms hang by her side and released her muscles and tightened them. She stared ahead blankly and opened her mouth a little so her lips made a small O.

“Oh my god—that’s fucking hot.” Kurt pressed his lips to hers and put his tongue against her lips and teeth. Her first kiss. Her body became electric. His breath reeked of beer and traces of cigarettes, but his shirt smelled of fabric softener. She opened her eyes, and Kurt put his arms around her. “You’re so cool,” he said as he held her hand.

“Thanks—I guess,” she said, looking down at her boots.

“I love all the shit you shared with me.”

“Really, it’s not weird?”

“Not at all. It’s awesome—so you’ve always wanted to be dead.”

“And you held something, a living being, as it died.”

He kissed her again. She closed her eyes and kept her mouth very still as he touched her tongue with hers. “Can you do that again?” he asked.

“What?”

“The gun in your mouth thing.”

She straightened her back against the concrete wall and let her arms hang. She opened her mouth, and this time she closed her eyes. She heard Kurt get up and place his feet on the ground, in front of her. She wondered what he was going to do. Every microsecond felt like an hour. Maybe he would lean over and kiss her again, since her mouth was open. Or maybe he would kiss her neck. She kept her eyes closed so she could stay in the moment. Her hands were getting sweaty, so she sat on them. Her knees were together, her legs stretched out, and her feet flexed in her combat boots. Then she heard a zipper right next to her ear. It was so loud that she could hear the zipper move down, tooth by tooth. She sat very still.

She pretended a gun was entering her mouth. Her body stiffened, then relaxed, as her mouth stayed open. She relaxed the muscles of her mouth, but kept her lips and tongue still. The deeper he was inside her mouth, the more still she became. She could no longer feel her breath. She had never been this still before. Her cheeks felt hard denim push against them, and still she did not clench her face. She heard his breathing as he touched her hair. She thought of him petting his dead cat Asterix. That thought, and her nose getting stuffed, made her cough.

Kurt stopped and took it out of her mouth. He zipped up his pants, and she opened her eyes. She wiped tears off her cheeks. He gave her his hand and helped her get up.

He led her inside and got her an orange pop from the blue cooler. She stood behind him so he couldn’t see her face. Alice saw them and said, “Reems, I was looking for you! Look, we gotta go. Hope that’s cool.”

Later, parked in the Datsun in Alice’s driveway, Alice asked, “What happened? You were gone for hours or something.”

“Um, nothing, you know, talking, and stuff.”

“Stuff?” Alice asked, raising her eyebrow.

“Yup. Stuff.”

“Like what? Were you picking flowers? What the hell?”

Rimi decided to change the subject. “So, Al, what did you do? What’s that guy’s name?”

“Oh, Gus, yeah, he was cool. We talked. And then made out a little,” Alice said.

“So, what do you mean exactly?” Rimi asked.

“Oh the details, sure. Second base, with tongue.” Alice looked intently at Rimi. “Rimi, what’s going on? The real question is what did you do?”

“Same thing, I think.”

“Like, he felt you up and kissed your tits? Like that?”

“No . . .” Rimi said as she looked out her window. “I don’t really know how it started, but all of a sudden, he put his—“

“Hold on! Did you fucking give him a blowjob? Is that what happened?”

“Yes,” Rimi said as she faced Alice, and then sighed.

“So . . . How was it? Are you okay?”

Rimi looked down. “Um . . .” she stammered, “it was weird.” Rimi couldn’t tell Alice what happened and how it ended. She couldn’t tell Alice that she didn’t know what to do, other than pretend that she was dead. She couldn’t tell Alice that she wanted to be dead.

Alice looked puzzled, then giggled. “Reems, don’t worry. He’s not going to say anything at all. And it’s like it didn’t happen. I mean, there’s like no physical evidence, you know. You can pretend it never happened. Trust me.”

When Alice dropped her off the next morning, Rimi walked into her single-story house, looking at the Ganeshas, Krishnas, and Lakshmis that looked back at her in every direction. By the fireplace stood a big carved wooden statue of Shiva and Parvati. Shiva, with his long hair in dreadlocked snakes, cupped Parvati’s breast. Parvati’s legs were parted, her thigh wrapped around Shiva’s legs, her eyes locked into his. His eyes looked right into Rimi’s. All of these years, how had she not really seen what Shiva and Parvati were doing?

Later, when Rimi saw her parents, she felt they could see through her, the shapes her lips made, where her tongue was, and the gulping in her throat. She kept applying Vaseline to her lips, and tried to not move her mouth in front of her parents. Yet she couldn’t stop thinking about not moving her mouth. All day, she kept wiping the side of her lips, stretching her facial muscles, making large gulping sounds, all while trying to not move her mouth at all.

That night she and her parents went to the Hindu temple in Lemont, about an hour away from Skokie. She wanted to disappear. In the car, she kept turning the cassette on her yellow Walkman, listening to Sinead O’Connor scream and whisper.

Rimi and her parents arrived at the temple at 8 p.m. There was a sea of brown faces, where everyone looked a little like her. She came to understand that for this puja, the Jagrata, they were expected to stay all night. Everybody sat on the floor in a semicircle, facing the giant stone statue of Mataji and the fire in front of her. Rimi felt herself breathe deeply, her stomach rising and falling.

But she didn’t understand—was Mataji the same as Sita, or was she Sita’s mother the Earth? Were they all avatars of the same oneness; was this oneness feminine; could oneness have a gender? She asked her parents. She asked their friends. She got different answers from different people and concluded that they didn’t understand either. She wondered if any Hindu actually understood Hinduism.

By 3 a.m., most of the little kids were sleeping in their parents’ laps and the teenagers were in the parking lot hanging out by the cars, while the adults and some older kids were sitting in the main room and drinking chai to stay up. Rimi didn’t know how to read the transliterated Sanskrit in the prayer books, so she snoozed until her mother prodded her, and she opened her eyes.

An old widow with a tight bun was walking towards the fire in a trance-like state. She began to swing her head ferociously, and all of her bobby pins popped out and fell at once. Her silvery hair resembled the blades of a windmill. As she got closer to the fire, she began to circle her hair in and out of the fire.

The old woman did this for a few minutes, yet she was not burned at all. The woman’s family and the pandit gathered behind her, as if holding onto her without actually touching her. Eventually, her body jolted to a more conscious state, and the old lady dropped to the floor and began crying. Her family was crying too. Then there was a roaring “Jai Mata Di” from everyone in the temple. Rimi’s lips moved too, as she whispered, “Jai Mata Di.”

She looked around the room, got up, and walked past the chai station to see if there were any fireflies out. She walked alone, away from the temple entrance, away from the crowds in the parking lot. She kept her eyes wide open, listening for any footsteps. She had finally stopped wiping her mouth. Rimi stood still, looking into the sky and the nearly full moon. The night was too cold for fireflies.

![]()

Swati Khurana is a writer and visual artist from New York City. Exhibition and screening highlights include: Art-in-General, DUMBO Arts Festival, Brooklyn Museum, Queens Museum (NYC); Chatterjee & Lal (Mumbai); Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo (Costa Rica); ScalaMata Gallery (53rd Venice Biennial); and Zacheta National Gallery of Art (Warsaw). She has received grants and awards from the Jerome Foundation and Bronx Council for the Arts. Her collaborative project with Anjali Bhargava, Unsuitable Girls, is on view at the Smithsonian Institution’s Beyond Bollywood exhibition until August 2015. Currently a Fiction MFA student at Hunter College, Swati is working on her first novel. www.swatikhurana.com

Swati Khurana is a writer and visual artist from New York City. Exhibition and screening highlights include: Art-in-General, DUMBO Arts Festival, Brooklyn Museum, Queens Museum (NYC); Chatterjee & Lal (Mumbai); Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo (Costa Rica); ScalaMata Gallery (53rd Venice Biennial); and Zacheta National Gallery of Art (Warsaw). She has received grants and awards from the Jerome Foundation and Bronx Council for the Arts. Her collaborative project with Anjali Bhargava, Unsuitable Girls, is on view at the Smithsonian Institution’s Beyond Bollywood exhibition until August 2015. Currently a Fiction MFA student at Hunter College, Swati is working on her first novel. www.swatikhurana.com