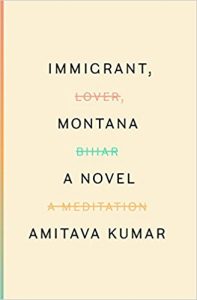

Immigrant, Montana by Amitava Kumar

Reviewed by Mary Ann Koruth

“Jennifer,” the first section of Amitava Kumar’s novel, Immigrant, Montana opens with a testimonial by a young man, prematurely guilt-ridden, and so, perpetually seeking pardon; he has left India for the United States to begin graduate studies. He arrives, a dark, disheveled traveler in line at the airport. Soliloquy follows soliloquy, as Kailash, the protagonist, explains his case to an imaginary white judge in a courtroom of the country of his choosing: “You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK…his eyes haunted…it is far from your thoughts and your assumptions to ask whether he has ever spoken soft phrases filled with yearning or what hot, dirty words he utters in his wife’s ear as she laughs and embraces him in bed.”

Is the nature of exile so complex that we who choose it, appoint the new country as the moral arbiter of our choice? Who else will forgive and heal us? The very fact that Kailash places himself at the mercy of judgement by a citizen of the country that granted him passage, so plaintively making the case for his dirtiest, rawest, truest, most private self, sends a clear message. For Kailash, India is the past, the future, America, and the struggle of passage is the present. This present is the subject of the novel more than the individual who lives it. And if an entire lifetime, or a significant portion of it, should be dedicated to this struggle, to assimilate without losing one’s sense of self, to continue to be recognizable to oneself, yet beloved in the eyes of the desired one — if this is the fallout of exile, then so be it. Look at me, says the immigrant, as a desiring, feeling human, ambitious for the life I have chosen, unable to justify my choice, but pursuing it nonetheless.

Kailash’s discovery of America is entwined with the discovery of sex, love and the women who make up the country: “I dreamed of being a writer, and even while fumbling with the clasp on Nina’s bra, I sought language for my experience.” The virginal graduate student explores the exhilarating shores of sexual discovery. As Kailash contemplates the positions—in bed and out of it—that he and his girlfriends might occupy, the reader sees a purely personal revolution unfold, that is equal parts sexual and political, real and rhetorical. The experience of sexual liberation and cultural freedom are synonymous, and Kailash sees one through the lens of the other. Conversations about love and lust cross over into conversations about the state and the histories, both present and past, that dog him.

“Yes, they ask me over at Immigration, Did you marry her for love? I’ll say, Yeah, I love the way she climbs on top and fucks me.” In the section called, “Nina,” sexual rapture meets literary muscle and though the resulting banter might not sound like regular pillow talk, it is very entertaining, because this is not a novel about sex. In a particularly stylized moment, the narrator comes out of the shower and sees his lover lying naked in bed, “…A lovely creature stretched on the dark sheet: on the inside of her thigh, in dark red lipstick, she had written Here…” Sleeping with and loving American women is part of Kailash’s acculturation. This metaphor is gorgeous, and gorgeously written. And Kumar informs us of the narrator’s own discomfort with it, just as we begin to question its veracity. Language and art are no substitutes for love and trust and sheer kindness.

Throughout the novel we are aware that the narrator, like ourselves, relates his story in hindsight. What will we learn? What does he learn? No doubt, Kailash approaches life in America, and sex, with a prepubescent zeal, and why not? Give it your all or give it nothing. How dilute our experience if we are not there for the ravishing. And so, all this with America. References to India on the other hand, are historical and scholarly. Kailash’s memories of his childhood hold a mirror to the devastation and violence that is at the heart of life in rural India, and especially in Bihar, Kumar’s home state. In all these references, we see a deep anguish scuttling beneath Kailash’s factual retelling of India’s colonial past and his own experience of family as a place of attachment and sorrow but little redemption. A cousin is raped, a mother loses both her children, an old woman on a plane fumbles at a toilet door, and Kailash is simply overwhelmed by the scope of these injustices. How much safer is Morningside Heights and the firm landscape of Columbia University. And yet, as Kailash admits, the redemptive quality of exile lies in its link to the past. Without the sadness and the hankering, there would be no happiness.

Immigrant, Montana is a supremely erudite, cerebral novel, primal at heart, with long interludes into political history. Filled with footnotes and images, it is a collage more than a story, nonchalantly plotless. But it returns, always to the carnal heart of our existence, the protagonist’s lust for life. And it is funny—even if a lot of the humor is in Kailash’s absurd and self-conscious attempts to open the gates of love—his words, not mine, the clichéd inside joke about clichés. Even as he omits the name of a town in Gujarat while seducing a lover with a story from his past, not because he might have forgotten it, but because he believes he has repressed it, as he moves from woman to woman in search of his own elusive self, we see a man and his peripatetic heart, and the pattern of his life. This is what we learn, and what he learns about himself—that his wanderings are his life, that the desire that drives his wandering defines him, and thwarted as he is by his own blunderings, these blunderings are a piece of who he is.

The novel finds its emotional voice and center in its last section, “Peter and Maya.” Here, the narrative lightens and lifts, as if its different rhythms suddenly synchronized. Though we see an awkward and flawed Kailash throughout, in these pages, he begins to see himself with compassion. Old loves and colleagues become helpmates. Flecks of clarity illuminate his understanding of himself and what he can offer to the wider world through his life and work. An unintelligible world begins to sort itself out.

![]()

Mary Ann Koruth’s love for the English language came from growing up in a family where fidelity to literature and grammar bore a moral dimension. Her writing and reviews have appeared in The Indiana Review, The Rain Taxi Review of Books and The Hindu. She has written for TheAtlantic.com while interning as web editor, and has covered art and culture for other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from Rutgers-Newark.

Mary Ann Koruth’s love for the English language came from growing up in a family where fidelity to literature and grammar bore a moral dimension. Her writing and reviews have appeared in The Indiana Review, The Rain Taxi Review of Books and The Hindu. She has written for TheAtlantic.com while interning as web editor, and has covered art and culture for other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from Rutgers-Newark.