What we write about when we write about writing. (A response to Yiyun Li).

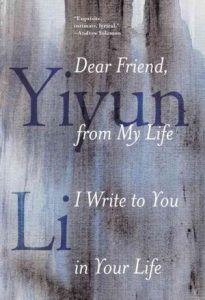

Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, by Yiyun Li.

Hardcover, 208 pages, Random House Inc. 2017

In “Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life,” Yiyun Li’s intelligent and deeply nuanced memoir on her life and her writing and the interminable connection between the two, she quotes from her novella, “Kindness”. The episode she describes is of a little girl who wants to buy chicks from a peddler. Because her father cannot afford them, two women in the market pay for them. She takes them home and cares for them, but they die, eventually. The girl steals eggs from her kitchen and cracks them open, washing out the yolks and whites. She then tries to return the dead chicks to the eggshells, trying to fit their tiny bodies into the halves, but finds that she is unsuccessful. The excerpt ends with the girl making this observation, “I have learned, since then, that life is like that, each day ending up like a chick refusing to be returned to the egg shell.”

Li’s assertion, throughout this book, is that she has abandoned her native tongue, Chinese, and adopted English as the language she writes in. In addition to giving up Chinese, but also, as a result of this choice, she has abandoned elements of her childhood in China, and would like to live in a world that is as unpopulated by memories of her life, growing up in China, as is possible. The book was written over a two-year period during which Li was hospitalized twice for suicidal depression.

Though the questions that Li raises, and the statements she makes, are about writing, they become questions about life and living. This is why her book is so unusual and so profound. In giving up a past, in renouncing it as completely and unambiguously as Li has chosen to renounce Chinese, surely her writing is informed and influenced by the vacuum created by that choice, as much as it would have been informed and enriched by embracing it. Li is the first to admit this — in life, as in writing, our selves are as much a result of what we choose to be as what we choose to not be. Like chicks refusing to return to the eggshells, we are what we give up. We can choose not to retrace our steps, but there is no erasing; the erasure of memory and the revisiting of it — aren’t these almost equally unreliable?

Why write autobiographically? Li asks this question pointedly. The word “I”, in English, is melodramatic, she writes. “In Chinese one can construct a sentence with an implied subject pronoun and skip that embarrassing I, or else replace it with we. Living is not an original business.” Li insists that she does not write autobiographically — because she does not, or did not, at the time of writing this book, have a “solid and explicable self”. She refers to a state of “unraveling” in between her hospitalizations. She writes to erase the self — but that is impossible, because nothing brings us closer to our truest selves than the practice of art.

I can often trace an autobiographical element to my stories. But that is not what I am interested in, for this piece. It is the sense of self that Li grapples with, and that she describes other patients in her hospital grappling with, a sense of self so flung into sadness that she wanted to erase it completely. I cannot pretend to understand the depth of Ms. Li’s despair, but I cannot be alone in having known despair and emptiness. I write to escape myself; writers like Li, are talented enough to do so successfully in their stories and novels. In my own poems and fiction, I fear vanity; how much of memory, of pain recalled, is mere indulgence? The “I” that Li suspects and would dispose of, raises a similar question for me. Do our individual selves matter enough to justify autobiographical writing? My answer is no, yet I cannot help returning to that elusive “I”. In any case, all writing is personal, so that trying to escape the “I” is a bit of a bluff. So much safer to publish journalism and criticism. Fiction and poetry are hard, but until I am certain of the validity—and quality–of what I create, a lot of my other writing will remain an escape.

An Indian colleague of mine was surprised when I told her during her farewell party in the office, that two years ago, she had asked me, as I walked through the lobby, to show her to her interview, and though neither of us knew it at the time, her future boss. She did not recall our interaction.

“Am I that forgettable?” I laughed, which was silly, because she was thinking of her job prospects in an empty lobby on a blue, cloudy day. Anyone else, in my place, would have done the same for her. Yet when I took my son to the doctor last week, he told me he remembered me from a year ago, when I visited him with my daughter. I was surprised that he would, because I was, at the time, thinking only of her. I don’t recall saying anything that would make him remember me, but he did. Our ideas about ourselves are consistent only in our own eyes. Writing, unlike life, has the advantage of hindsight, which makes for more predictable results. You might be able to identify a writer by her voice or her oeuvre, but the truth of who she really is can be impossible to lay a finger on. And so, the writer, in search of a self, keeps writing, and her readers pick up the thread wherever she leaves it, in her books.

I have not yet completed Li’s book, partly because I want to linger and bathe in her many aphorisms, her entangled thoughts, which defy and provoke each other, reminding me that uncertainty is a state worth having.

What I take away from it, as far as my own writing is concerned is this: if I could speak with as much assurance as I write, how much more memorable I would be to the people I meet. But the page is more patient than a person, though what I write, I write for people. Perhaps I am simply too careful in relationships, even casual conversations — the fear of causing damage or hurt by saying what I think, or bringing into question my own immaturity, the fear of revealing weakness, seals my lips and distorts what I would naturally say. Writing, both fiction and non-fiction, is a lifelong exploration of the gap between truth and what I think is the truth — between absolutes and relatives, between the objective and the subjective, between negative space and positive space. I seem to have assumed that the truth (of life, of art) is unknowable — distant from my own experience of it. This is a form of posturing, but it is also true. A digression from things is often only a path of return. I can only speak for myself, and so, I write.

– Mary Ann Koruth

So elegantly expressed !

Thank you so much Shyla aunty. I’m so glad you enjoyed reading this.

Absolutely enjoyed reading your blog! Beautifully written, Shalu!

Shelly

Shelly – Thank you for writing and taking the time to comment. Glad you liked it!